In the words of Abraham Lincoln, democracy is defined as, ‘Government of the people, by the people, for the people’. In the Indian context, when we say "democracy is the government by the people" it means it is a system in which the government of a country is elected by the people. The preamble of the Indian constitution seeks political justice adhering to rule of law and the absence of arbitrariness. Ultimately, the main objective of the election is to form the government. The elections are conducted by an independent constitutional body - the Election Commission of India. The political party, or political alliance with the maximum number of winning seats is invited to form the government. These political parties have always played a crucial role in a representative democracy like India.

In the year of 1951-52, the first-ever elections were conducted after Independence. The Indian National Congress won a landslide victory, winning 364 of the 489 seats post which, there was a ‘Congress system’ in India for a long time. But change is inevitable, and soon new regional political parties started emerging. These political parties played a significant role in Government formation by creating diversity while simultaneously resulting in the nuisance of defecting representatives. During this period, political morality was at a low ebb and corruption was at a high pace.

Day by day and election after election, the disease of defection started weakening the ethos of the political system in the country.

The quest for power took over everything. The elected representatives started switching sides from one party to a party that otherwise lacks the requisite number to form the government. Then came the concept of ‘horse-trading’ where political parties try to bring in members from the opposition to gain a majority in the assembly, by resorting to unapproved techniques such as offering ministerial perks and financial benefits. It is almost the same as bribing.

Until 1967, this immoral (though not illegal at that time) behaviour reached its peak when a Haryana MLA, Gaya Lal, changed his party twice within a few hours and thrice within a fortnight. Since then the disease of defection was summed into a sarcastic phrase called “AYA RAM GAYA RAM". Between 1967 to 1971, 142 MPs and 1900 MLAs had changed their political parties.

Just. Soli J. Sorabjee called this to be a disloyalty to duty. This is a breach of faith, not only of electors, but also of a political party on whose ticket they were elected.

As the events ensued, the condition started worsening. On 8th Dec 1967, Lok Sabha constituted a high-level committee called ‘Committee of defection’ which was chaired by then Home Minister Y B Chavan. As per the recommendations of the committee, 32nd Amendment Bill was introduced but it lapsed. After that, the second attempt was made by the 48th Amendment Bill, 1979 but it was also withdrawn. After the assassination of Indira Gandhi, when Rajiv Gandhi became the Prime Minister, he assured the people that the government is bringing a law to curb the menace of defection.

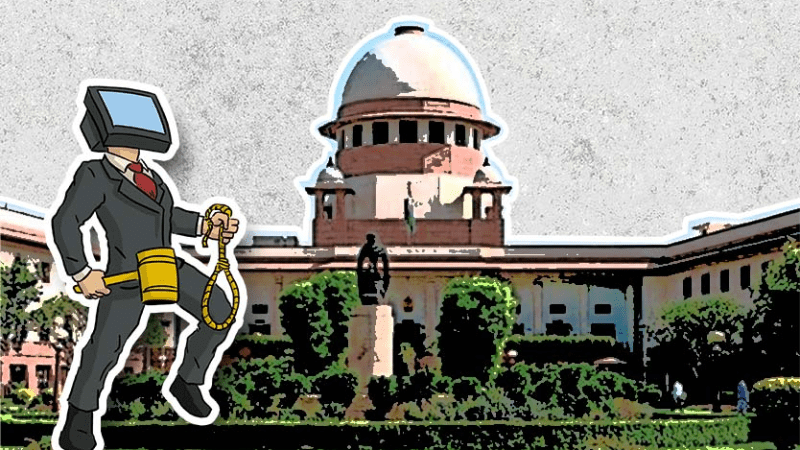

Finally, with the help of the 52nd Amendment Act of 1985, the 10th schedule was inserted in the Constitution of India dealing with the Anti Defection Law. The main objective of this Act was to discourage and curb the practice of defection and to bring political stability. The Act applies to both Parliament as well as state assemblies. The law punishes MP/MLAs for defecting from their party by taking away their membership of the legislature. It gives the speaker of the legislature the power to decide the outcome of defection proceeding. If an MLA is disqualified, he can no longer act as an elected representative of his constituency.

The grounds for the defection under this law are: Firstly, when a party’s legislator “voluntarily gives up” membership of their political party. Secondly, if a legislator votes in the House against the direction of his party and his action is not condoned by his party, he can be disqualified. However, these grounds are subject to a few exceptions. The first one is if 1/3rd members of the party are splitting to change the party. But this exception was taken off by the 91st Amendment Act, 2003 as it resulted in large scale defections, and lawmakers were convinced that the provision of a split in the party was being misused. The second exception is that if 2/3rd members merge with another party.

In the 1992 case of Kihoto Hollohan vs Zachillhu And Others, the constitutional validity of the 10th schedule was challenged. The apex court upheld the constitutional validity of the 10th schedule and rather stuck down some provisions, which were depreciating the power of judicial review and violating the basic structure.

This act was misused on various occasions. There was confusion about the meaning of the term ‘voluntarily giving up the membership of his party’. In this regard, the Supreme Court says that the reasonable inference can be drawn from the conduct of the legislator. The other loophole is the Speaker of the House enjoys vast powers on disqualification proceedings. By this authority, the non-partisan constitutional office has been dragged into the party politics. In a number of cases, the Supreme Court has taken the stand that judicial review should not cover any stage before the making of a decision by the Speakers/Chairman. On this ground, various expert committees have recommended that rather than the Presiding Officer, the decision to disqualify a member should be made by the President (in case of MPs) or the Governor (in case of MLAs) on the advice of the Election Commission.

The other point of concern is that Indian Politicians transverse across the complications of the act just before elections, because there is no such law in our country to control this menace before the election. To bypass the provisions of the act, MLAs resign from the legislature and then join another party. There are intentional delays in deciding the defection petitions since it gives a way out from the provision of the act. It ensures the loyalty of defecting MLAs, as the sword of losing their seat in the assembly keeps hanging over their heads. And delaying prevents the judiciary from interfering in defection cases. Hence, in a judgment, the Supreme Court has held that the Speaker of the Legislative Assembly should decide on a petition seeking disqualification within three months, in the absence of exceptional reasons.

The defectors have no fear as they mostly join the ruling party, and the speaker who has the power to disqualify belongs to the ruling party. The act to some extent undermines the power of the ballot, for it shows no concern about the electorates who have elected these representatives.

The apex court on many occasions has suggested that “the Parliament should amend the Constitution to provide for an independent mechanism, such as a permanent tribunal headed by retired judges to decide disputes under 10th schedule”.

The law certainly has been able to curb the evil of defection to a great extent. But as time passes, there is also a need to reassess the law to plug the loopholes, if any.

While repairing a machine, there is the limit to which you can tighten a screw with the screwdriver. This equally applies to every act, and in the case of defection law, more stringent provisions may jeopardise the fundamental freedom of speech and expression of a member of the house. I think it's not always the lawmakers to be blamed, but along with them,law followers also need to be more law-abiding than being the lawbreakers. After all, there is a difference between introducing a law with loopholes and using the existing provisions as loopholes.

- Adv. Prachi Patil

ppprachipatil19@gmail.com

(The writer is a practising lawyer at the Pune District Court and the Family Court, Shivajinagar)

Tags: Adv Prachi Patil Law Anti Defection Law Load More Tags

Add Comment