Nani A. Palkhivala in his book ‘We the People’ emphasises the importance of the Independent Judiciary by saying that an independent judiciary is the very heart of a republic. A French philosopher Montesquieu for the first time propounded the concept of independence of the judiciary as he believed in the concept of separation of power amongst the three branches of government that is the Executive, legislature, and judiciary.

As far as the Indian constitution is concerned, there are many constitutional provisions which speak of the Independence of the judiciary & separation of power. However, the most crucial provision which is looked at to preserve judicial integrity is the power to appoint, transfer, promote and elevate judges. If we speak of the union judiciary Article 124 comes into the picture (while article 217 applies to High Court judges).

Article 124 in simple words states that - "Every judge of the Supreme Court shall be appointed by the President of India after consultation with the Chief Justice of India".

Whereas, Article 217 says that- "Every High Court judge shall be appointed by the President in consultation Chief Justice of India, Governor of that state and Chief Justice of that High Court".

Apart from this, some other relevant provisions in this regard are: Article 222 empowers the President to transfer judges from one High Court to another after consultation with the Chief Justice of India.

There is also a provision which enables the President to appoint additional judges for a maximum period of two years to meet the temporary increase in business or work arrears in the High Courts.

If we look at these provisions there is a word common in each of them as 'consultation' (between the President and Chief justice of India). The word consultation was primarily inserted by the Constitution makers with the hope to maintain a balance of power between the executive and judiciary. But since then, some historical events have made the pendulum swing from executive to judiciary and vice versa. The word 'consultation' has gone through a lot of interpretations through various judicial pronouncements until we reach the current scenario. However, even after so many years of the commencement of the Constitution of India, there is still a debate alive as to how to bring a balance between executive and judiciary regarding appointments and transfer of judges.

For the early few years of India as an independent democracy, the judicial appointments were made the way it was expected to be in adherence to the Constitution of India. The opinion of the Chief Justice of India and judges of the appropriate High Courts had a huge say in the appointment process of judges. There has also been an established convention to appoint the senior-most judge of the Supreme Court fit to hold office, as the Chief Justice of India, where the retiring Chief Justice of India recommends the name of his successor. However, contrary to this in the '70s an unprecedented act of suppression happened which left India amazed. Justice A N Ray was appointed as Chief Justice of India bypassing the three senior-most judges of the Supreme Court, Justices J M Shelat, K S Hegde and A N Grover who had not passed the judgments favourable to the existing government. This was the real beginning of the power struggle, a battle of supremacy of power between the executive and judiciary.

After this came the black period for the Indian democracy where a national emergency was declared which lasted for 21 months from 1975 to 1977. This was a period when almost 56 judges were transferred from their home High Courts to High Courts in other states as a punishment for not following the policies of the then government. One of these judges, Justice Sankalchand Seth was transferred from the Gujarat High Court to the Andhra Pradesh High Court for the reason of ‘national Integration’. He challenged the constitutional validity of presidential notification before the Hon’ble Gujarat High Court. Where Hon’ble Gujarat High Court allowed the petition on the ground that the President of India had not effectively consulted the Chief Justice of India. Then after, the Union of India went into appeal before the Hon’ble Supreme Court and assured that it would transfer Justice Sheth back to Gujarat High Court. Nevertheless, the Supreme Court refused to recognise the right of the judge to be consulted before his transfer and also did not look into the legality of transfers to punish independent judges. (Union of India Versus Sankalchand Himatlal Sheth, 1977)

For the second time, the matter came before the Supreme Court in S. P. Gupta V. Union of India, 1982 famously known as the First Judges Case. In that case, several writ petitions were filed in different High Courts and were disposed of by a bench of seven judges of the Supreme Court. Some of these petitions challenged the validity of a circular letter of the Union Law Minister addressed to the Chief Ministers of the states. The main crux of this letter was to obtain the consent of Additional judges of the High Courts and upcoming judges to be appointed as permanent judges or judges as the case may be in other High Courts of the country. The circular was said to be issued to ‘further national integration’ however, it was called an attempt to narrow down the judicial independence. Most of the judges held that:

1) Judges could not be transferred from one High Court to another as a punishment.

2) Consent of a High Court judge is not a precondition of his transfer.

3) Confirmation of an additional judge as a permanent judge is not a right in itself.

And lastly, the most important issue was the dynamics of power between the executive and judiciary in the appointment of judges. Wherein, the Court held that the Chief Justice of India’s opinion in the appointment of judges was not to receive primacy which meant that the word consultation means a mere consultation and the decision of the President shall be final. This was the case where the Supreme Court compromised its own independence.

The majority decision in the First Judges Case was generally found unsatisfactory by the legal fraternity and was hugely criticized. They asked for a creation of a collegial body with primacy to the judiciary for the appointment and transfer of judges. Contrary to this the Law Commission of India recommended the creation of an eleven-member National Judicial Service Commission chaired by the Chief Justice of India and a consequential constitutional amendment.

In the late 1980s the Supreme Court in one of its decisions observed that its decision in the first judge's case requires reconsideration by the larger bench of judges. (Subhash Sharma Versus Union of India, 1991). Hence the question of judicial appointments and transfers was referred before the nine judges' bench of the Supreme Court in the Supreme Court Advocates on Record Association Versus Union of India, 1991. (The second judge's case) It overruled the first judge's case. In simple words, the Court held that the word consultation must be participative. As a basic rule, both organs that are executive and judiciary should make a collective decision but when there is a conflict the decision of the Supreme Court will prevail. The then Attorney-General drew the Court's attention to the fact that the then Chief Justice of India had constituted a panel of himself and five of the then-senior judges and submitted that this precedent should be treated as a convention and institutionalised. The Court noted that presently, and for a long time now, that collegium consists of the two senior-most Judges of the Supreme Court and CJI. This is how the Supreme Court also decentralised power conferred upon the CJI/chief justice of the relevant High Court by granting the power to the plurality of judges through the collegium colleague system.

Dhananjaya Y. Chandrachud (Chief Justice of India)

This was followed by the third judge's case which was a reference made by the President of India under Article 143 to the Supreme Court of India. The Court held that the appointment of judges shall be according to the principles led down in the second judge's case the only revision it made was that for the appointment of judges to the supreme Court the collegium would consist of the CJI and four senior-most judges. The collegium system for appointments emerged out of executive interference with the judiciary during and after an emergency.

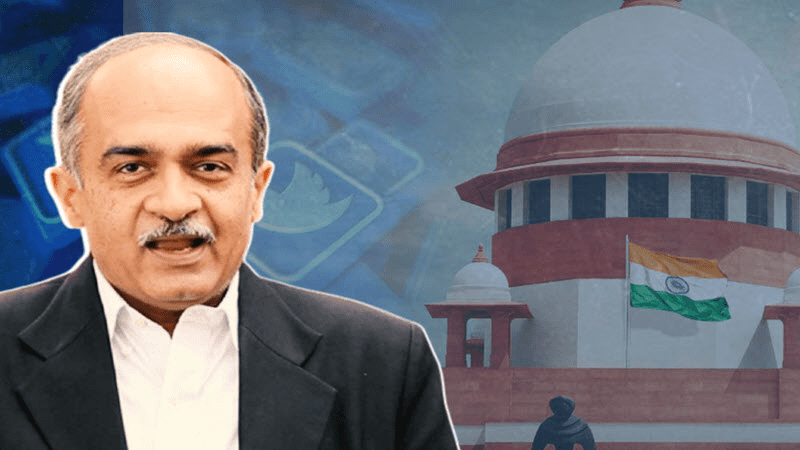

Meantime there were regular political calls and even formal attempts to create a new system of appointments but none of them led to any tangible change. However, in 2014 a huge change was witnessed with the enactment of the 99th constitutional Amendment to the Constitution and the National Judicial Appointments Commission Act. This was due to the growing concern about judicial accountability, the collegium system's opaque (vague) character, lack of transparency in the appointment process and so on. This change was challenged in the case of the Supreme Court Advocates on Record Association Versus the Union of India, in 2015. The Supreme Court held that it violates the basic structure of the constitution. The National Judicial Appointments Commission Act was struck down stating its vague provisions, poor drafting and so on. At the same time, the Supreme Court acknowledged the failure of the collegium system and vowed to improve it.

To date, the collegium system is still intact but recently in debates as Law Minister Rijiju criticised it saying that judges only recommend the appointment or elevation of those they know and are not always the fittest person for the job. He called the system 'opaque and filled with intense politics'. Answering to this CJI Dhananjay Chandrachud said, "No constitutional institution or model is perfect. We need to strengthen the collegium system by ironing out the creases and by being responsive to criticism". The Supreme Court has also taken up a plea challenging the collegium system.

Sources:

1) 10 judgments that changed India - Zia Modi

2) We the People- Nani A Palkhivala

3) Rethinking Public Institutions in India - edited by Devesh Kapur, Pratap Bhanu Mehta Milan Vaishnav

- Adv. Prachi Patil

ppprachipatil19@gmail.com

(The writer is a practicing lawyer at the Pune District Court and the Family Court, Shivajinagar.)

Tags: Supre Supreme Court Chief Justice Dhananjay Chandrachud Prachi Patil India Government Load More Tags

Add Comment