In India, the central and state legislatures are responsible for the law-making, the central and state governments are responsible for the implementation of these laws, and the judiciary (Supreme Court, High Courts and lower courts) interprets these laws. However, there are several overlaps in the functions and powers of the three institutions. One such role is under Article 123 of the Indian Constitution which grants the President certain law-making powers to promulgate Ordinances when:

1) Legislature is not in session

2) Immediate action is required

3) subject to Parliamentary approval during the session.

The Governor of a state can also issue such Ordinances under Article 213 when the state legislative assembly (or either of the two Houses in states with bicameral legislatures) is not in session.

It was argued in DC Wadhwa vs. the State of Bihar (1987), that the legislative power of the executive to promulgate Ordinances is to be used in exceptional circumstances and not as a substitute for the law-making power of the legislature. Here, the court was examining a case where a state government, under the authority of the Governor, continued to re-promulgate ordinances, that is, it repeatedly issued new Ordinances to replace the old ones, instead of laying them before the state legislature. A total of 259 Ordinances were re-promulgated, some of them for as long as 14 years.

The Supreme Court argued that if Ordinance making was made a usual practice, then creating an ‘Ordinance Raj’, the courts could strike down re-promulgated Ordinances. Now the question is why a sudden discussion about ordinance making process? It is because many states are introducing their laws by misusing this provision which is a topic of concern and in-depth discussion.

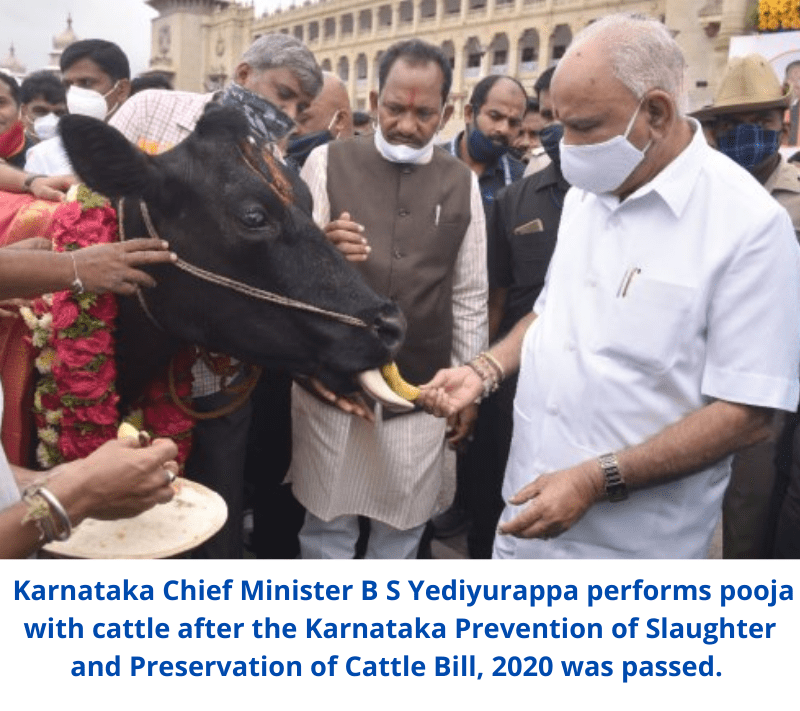

Recently, the Karnataka government promulgated an ordinance due to its inability to get the bill passed in the Legislative Council. Now, Karnataka Prevention of Slaughter and Preservation of Cattle Bill, 2020 has become law. In India, the legislation relating to the prevention of slaughter of cows and its progeny is said to be governed by Article 246 of the Constitution of India read with Schedule 7 List II (entry 15). It means that the states are empowered to form laws regarding the same.

Recently, the Karnataka government promulgated an ordinance due to its inability to get the bill passed in the Legislative Council. Now, Karnataka Prevention of Slaughter and Preservation of Cattle Bill, 2020 has become law. In India, the legislation relating to the prevention of slaughter of cows and its progeny is said to be governed by Article 246 of the Constitution of India read with Schedule 7 List II (entry 15). It means that the states are empowered to form laws regarding the same.

Before discussing the provisions of this new law, we must go back to the origin of the discussion and need to understand the importance given to cows in our society as compared to other animals. The importance and respect for the cows under the Hindu religion comes from the doctrine of the sacredness of cow. This principle is of relatively recent vintage in Hinduism and dates not to Rigveda, but the Gupta dynasty.

On the other hand, the Muslims were traditionally beef-eaters and with a religious practice of slaughtering cows on Bakr-Id. But other than Muslims, there were, and still are, other communities for whom beef has been a staple food for their survival as it is cheap to buy. If we look at the colonial period, this was a constant cause of communal tensions. Muslims were told by the law that they could slaughter cows provided that they did so in a walled enclosure, away from the gaze of Hindus, and discreetly without much fanfare.

If we look at the movement for the protection of the cow and against the consumption of beef, it dates back to centuries ago. One of the reasons for the first widespread rebellion against the British colonial ruler, in 1857, was when there were rumours that the cartridges of the rifle which was required to bite off with mouth, were made of pigs and cows. This angered both Hindus and Muslims.

In 1870, the first organised cow protection movement began in Punjab by the Sikh Kuka sect. In 1881, the organised political movement against cow slaughter in India began with the rise of cow and agriculture protection committee by Dayananda Saraswati. Though he offered the economic argument, the main purpose of establishing the committee was to build Hindu solidarity for the protection of cows.

Each member of the committee was called as 'Gaurakshak'. This committee filed a petition for a permanent ban on cow slaughter. But then came the ruling of the High Court in 1886 that the cow was not an object within the meaning of Section 295 of IPC, and Muslims who slaughtered cows can't be held liable under this section.

After this judgment, cow slaughter increased by a huge number. The leaders of the cow protection societies made provocation speeches to arouse Hindu sentiments, and on the other hand, Muslims also formed their organisations and initiated a movement to reinforce their faith. The tension between the two communities became so tight that it led to many communal riots, resulting in heavy loss of life and property. It also affected the economic relationship between these two communities as they stopped doing business with each other.

After independence, the new constitution declared India to be a secular state. The citizens were guaranteed full freedom to profess and practise any religion, subject to reasonable restrictions. However, the sensitive issue of cow protection continued to create serious obstacles, causing hindering the government from following the principle of secularism.

In the constituent assembly, two bills regarding cow protection were moved independently by Congress members Thakur Das Bhargava and Govind Das. The former wanted to ban the slaughter of useful animals, while the latter wanted to ban slaughter of all types of cattle. They wanted this to be a provision under the fundamental right chapter.

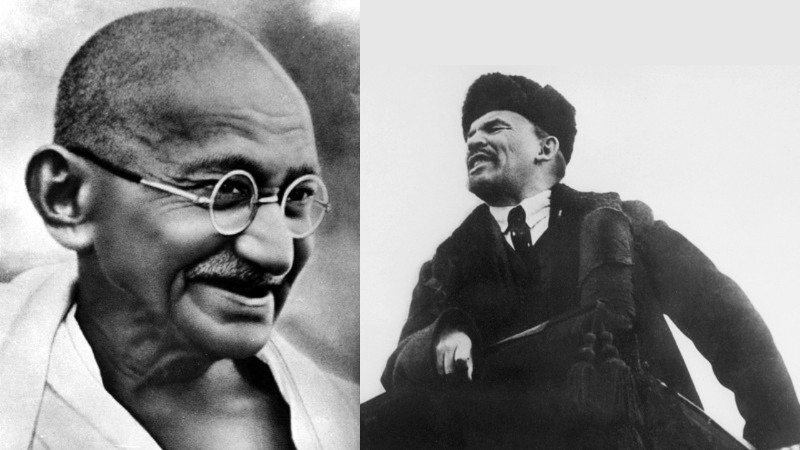

Though Bhargava's proposal was accepted, it reflected under Article 48 of the Constitution as a directive principle of state policy and not as a fundamental right. In pursuance of this provision, many states enacted their respective laws. Leaders like Mahatma Gandhi and Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru strongly opposed such legislation since the beginning. In 1955, Mr Bhargava introduced the Indian Cattle Prevention Bill intending to ban cow slaughter in the whole nation, where he placed economic as well as religious consideration to ban cow slaughter. In November 1966, at least 8 people were killed in violence outside the Indian Parliament when Rameshwarananda, a legislator from Bhartiya Jana Sangh along with the Hindu monks marched to parliament, demanding a nationwide ban on cow slaughter.

Though Bhargava's proposal was accepted, it reflected under Article 48 of the Constitution as a directive principle of state policy and not as a fundamental right. In pursuance of this provision, many states enacted their respective laws. Leaders like Mahatma Gandhi and Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru strongly opposed such legislation since the beginning. In 1955, Mr Bhargava introduced the Indian Cattle Prevention Bill intending to ban cow slaughter in the whole nation, where he placed economic as well as religious consideration to ban cow slaughter. In November 1966, at least 8 people were killed in violence outside the Indian Parliament when Rameshwarananda, a legislator from Bhartiya Jana Sangh along with the Hindu monks marched to parliament, demanding a nationwide ban on cow slaughter.

The cow slaughter in some form is now banned in a majority of states in India. Most of the state laws on cow protection are modelled after the National law, Prevention of Cruelty to Animal Act, 1960. Under most of these laws, cow slaughter is a cognizable, non-bailable offence, and the burden of proof is often on the accused. The 2020 Karnataka law of banning cattle slaughter is a harsher version of a law passed in 2010. It aimed at banning all forms of cattle slaughter by recommending stringent penalties for violators. The bill was postponed in 2013 after it failed to get the Governor’s assent.

There are some landmark pronouncements of the honourable Supreme Court in this regard:

The Supreme Court in Mohd Quarashi and another v/s state of Bihar, (1958) had the first opportunity in the post-independent India to adjudicate on the constitutionality of laws banning cow slaughter. The constitutional validity of 3 enactments banning the slaughter of cows passed by the states of Bihar, UP and MP were heard together by the court.

Additionally, the Bihar statute also banned the slaughter of buffaloes (male, female and calves). In this petition, petitioners argued that the ban on cow slaughter violated their rights to free exercise of religion and to pursue the occupation of their choice. To this, the court held that the statutes banning cow slaughter did not violate the right to free exercise of religion. It also held that the ban on the slaughter of bulls, bullocks and buffaloes ( male or female ) was justified, only when they had ceased to be useful. A total ban on the slaughter of calves and cows, whether useful or otherwise, was justified.

This judgment was criticised in two aspects. Firstly, the court used the criterion of usefulness for a ban on the slaughter of buffaloes, bullocks and other categories of cattle; but why was the same criterion not applied to the slaughter of cows? (Smith 1963) The retired Chief Justice P.B. Gajendragadkar, who was also a party to the decision on the above case, later admitted the force of Smith's comment on the discrimination between cows and other categories of milch cattle for slaughter (1971). The second aspect of the criticism was - to take away an alternative is an interference with the religious freedom of a community.

After this decision, some states started enacting laws, that made it very difficult for a person to establish that the cattle had become useless, by putting the restrictions till the age of 20-25 years. Hence, in Abdul Hakin Quraishi V State of Bihar, 1961 the court struck down such provisions and held that once cattle reach the age of 15, they generally become useless. The age of usefulness was later increased by the Supreme court to 16.

The age-long jurisprudence in the case of Mohd Quarashi and another v/s state of Bihar, (1958) was altered by the Supreme Court in 2005, when during the State of Gujarat v Mirzapur Moti Kureshi, the court upheld the total ban on the slaughter of bulls and bullocks. The court rejected the factors of 1958 judgment to invalidate the ban on the slaughter of useless bulls and bullocks.

In 2016, the Bombay High Court upheld similar provisions in a Maharashtra Law which imposed a ban on the slaughter of cows, bulls and Bullocks. But at the same time, the court struck down certain provisions and held that-

1) the impugned statute could not prohibit the transfer of cattle outside the state for slaughter

2) it could not prohibit the possession of beef within the state which was obtained from the cattle slaughtered outside the state as this violated a person's right to privacy.

3) the provision which placed the burden of proof on the accused was also struck down.

Then in 2017, the Central government enacted rules, which said that a person could not bring cattle to an animal market unless he provided a written declaration that the cattle were not being brought there for slaughter. It also barred those, who purchased cattle at an animal market, from slaughtering them or sacrificing them for any religious purpose. The rules applied not merely to bulls, bullocks, cows, buffaloes, steers, heifers and calves, but also camels.

Then in 2017, the Central government enacted rules, which said that a person could not bring cattle to an animal market unless he provided a written declaration that the cattle were not being brought there for slaughter. It also barred those, who purchased cattle at an animal market, from slaughtering them or sacrificing them for any religious purpose. The rules applied not merely to bulls, bullocks, cows, buffaloes, steers, heifers and calves, but also camels.

The Madras High Court granted a stay of some of the provisions of the rules, and the government has said that it will be reconsidering the rules altogether. Again in 2021, the apex court noted that either government should change these rules or the court will order a stay. Observing this, the bench had then disposed of a bunch of pleas challenging the rules, observing that the stay orders passed by the High Courts are applicable throughout the country.

The understanding of the provisions of The Karnataka Prevention of Slaughter and Preservation of Cattle Bill, 2020 will make things more clear on the topic. This law repeals the old law of 1964. It defines cattle for the sake of this act as, "cow, the calf of a cow and bull, bullock, he or she buffalo below the age of 13 years."

There is a total prohibition on cattle slaughter irrespective of any law, custom, usage to the contrary. The act restricts the transport of cattle within the state for slaughter. It also restricts the transport of cattle outside the state for slaughter, except for permits issued by the competent authority, for the bonafide agricultural or animal husbandry purposes. The act prohibits the sale, purchase or disposal of cattle for slaughter.

The act provides the power of search and seizure of premises, used or intended to be used, for the commission of such offence. The Bill also terms shelters established for the protection and preservation of cattle registered with the Department of Animal Husbandry and Fisheries as ‘gaushalas’. The penalty provided under the act ranges from 3 years to 7 years with a fine from Rs. 50,000 to 1 Lakh to 10 Lakh. It also prescribes punishment for the second and the subsequent offence. The offence under this act is cognizable.

The act exempts the slaughter of the cattle operated upon for experimental or research purpose at the institution established, conducted, or recognised by the state government. It also exempts the certified slaughter for the cattle suffering from the disease is contagious to other cattle, as well as one suffering from the incurable disease or is terminally ill.

Experts have noted several ill-effects of such kind of legislations. The Karnataka Prevention of Slaughter and Preservation of Cattle Bill, 2020 also has some drawbacks. The cow slaughter campaign has caused mob violence and mob lynching on many occasions. In July 2018, a three-judge bench of the Supreme Court passed a series of directives for 'preventive, remedial and punitive' measures to address the mob violence and killings.

If we look at the role of police, it is seen that they play bias in responding to cow-related violence. This includes delay in filing FIR and registering cases against victims or witnesses. Often, the witnesses turn hostile because of the threats from the police or the accused and their supporters. There are many cases where police fail to protect the witnesses as India does not have a national witness and victim protection law.

The cow protection movement is impacting agriculture, trade and livelihoods. It is hurting farmers and herders by affecting their right to livelihood. Farmers often supplement their incomes and food requirements by maintaining and trading livestock and selling dairy products. With the increase in the mechanisation of agriculture, the demand for draught cattle such as bulls and oxen has declined, and male calves are often sold. Farmers also sell unproductive and aged cattle. As more and more farmers are forced to abandon their cattle, there has been a significant rise in the numbers of stray cattle, resulting in anger among farmers whose crops are at risk. After a cow or buffalo stops producing milk, farmers usually sell them as it is a burden to maintain unproductive cows. This is a part of the chain in the dairy business.

If we stay specific to the bill and speak, it forces farmers to nurture them. And if this whole chain is broken, it will ultimately collapse the dairy farming business. It is said that the government will open gaushalas to take care of abandoned cows. However, this requires a long process of permissions from understaffed veterinary offices, and the government has not allocated any funds to build enough shelters for stray cattle.

The Supreme Court, in 1955, noted that beef is one of the cheapest sources of nutrition for the scheduled castes and scheduled tribes, many of whom have low incomes. This law has denied many lower-income groups access to cheap nutrition and their decades-old eating practices.

Whenever Mahatma Gandhi was asked on the topic of the ban on cow slaughter, he used to say-, "In India, no law can be made to ban cow slaughter. I do not doubt that Hindus are forbidden the slaughter of cows. I have been long pledged to serve the cow. But how can my religion also be the religion of the rest of the Indians? It will mean coercion against those Indians who are not Hindus."

Gandhi urged in 1947 discourse that the Indian Constitution must not ban cow slaughter. But he died long before the Constitution was finalised, and that document, alas, included a directive principle, with many caveats, aiming for a ban on cow slaughter. Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, while showing his opposition to such kind of laws, said, "I wish some other animals including human beings might be treated likewise."

Even if we decide to not to look at the religious grounds, we must think about the economic grounds while understanding such laws. Such laws will have the worst long-lasting effect on the dairy industry that goes hand in hand with farming. Such laws are also bothering the right to chose the food, and are also taking away a good source of nutrition.

- Adv Prachi Patil

(ppprachipatil19@gmail.com)

(The writer is a practising lawyer at the Pune District Court and the Family Court, Shivajinagar)

Sources:

1) Republic of Religion- The rise and fall of colonial secularism in India, ch. 1: holy cow (2020)

2) ISS Occasional papers- " Cows and cow slaughter in India" S M Batra - Institute of social studies. The Hague- The Netherlands ( July 1981)

3) Human Right Watch: Violent cow protection in India- Vigilant groups attack minorities(2019)

Tags: cows cow slaughter cow slaughter ban gaurakshak gaushala cow slaughter laws adv prachi patil Load More Tags

Add Comment