“I (A) take thee (B), to be my lawful wife (or husband)”

This is a mandatory oath for those who wish to marry under the Special Marriage Act, 1954, also known as the civil marriage law. The primary object of this act is to govern interfaith or inter-caste marriages, or even for those who want a secular marriage. A marriage performed with religious rites can also be registered under this Act.

The Special Marriage Act recently came into the spotlight when a renowned jewelry brand, Tanishq, took down its latest advertisement after the controversy broke out as it showed Hindu-Muslim Marriage. Some believed that the ad - which shows a Hindu woman who married into a Muslim family, celebrating her baby shower with her in-laws - was promoting love jihad.

A large section of social media asked people to boycott the advertisement. There was also news of mob attacks on Tanishq stores in different parts of the country. After all this turmoil faced by the brand, many renowned personalities came in support of Tanishq stating that those who are opposing the ad, might have forgotten about the Special Marriage Act. Some even questioned that by not speaking up on this topic, are we normalizing hate between the communities?

A large section of social media asked people to boycott the advertisement. There was also news of mob attacks on Tanishq stores in different parts of the country. After all this turmoil faced by the brand, many renowned personalities came in support of Tanishq stating that those who are opposing the ad, might have forgotten about the Special Marriage Act. Some even questioned that by not speaking up on this topic, are we normalizing hate between the communities?

"ignorantia legis neminem excusat" is a Latin legal phrase which means that "ignorance of the law is not an excuse". If we exercise it in a simple connotation, it means not knowing that the law is harmful. The law is harmful not only on a personal level but also at the social level. Hence, in this context, we need to know about the Special Marriage Act, 1954.

When we speak of any enactment, its history depicts a lot about its existence, its provisions, and its structure. Similarly, the Special Marriage Act also has a historical background, which has a far-reaching impact on today's enactment. British rulers of India, from the very beginning of their rule, had adopted the policy of retaining and protecting the traditional individual laws of various religious communities. All the regulations and laws enacted had recognized the existence of the personal Hindu and Muslim laws and guaranteed their continued application.

They remained intact to their policy till 1841 when the first law commission drafted a bill and included in its provision a significant reform affecting the personal laws of Hindus and Muslims. The intent behind this move was to remove the hurdle of loss of property of those, who were influenced to convert to Christianity. Starting from the Bengal province, such a change in personal laws was implemented all over British India by enacting the Caste Disability Removal Act, 1850, which is also known as the Freedom of Religion Act.

Gradually, the British took the legislative entry in the field of succession by enacting the Indian Succession Act, 1865. They also made changes in marriage laws by enacting the Indian Divorce Act as well as the Christian Marriage Act, 1872. But the marriage and divorce laws of Hindus and Muslims were left intact.

By the middle of the 19th century, the Brahmo Samaj had fully established itself as a progressive religious section by not agreeing with a specific aspect of orthodox Hinduism. Their movement in demanding directions of progressive law gave momentum to the feelings already existing in the society that India needed a secular marriage law.

During this period, Sir Henry Maine introduced the draft of the secular marriage Bill in the Central Legislature. The bill met vehement opposition - both on the floor of the legislature as well as outside it. When it was finally enacted in March 1872, its provisions allowed the marriage, only on a declaration made by two persons, that they did not profess Hindu, Buddhist, Sikh, Jain, Muslim, Christian, or Parsi religion. The act had no provision as to the dissolution of marriage and its succession.

During this period, Sir Henry Maine introduced the draft of the secular marriage Bill in the Central Legislature. The bill met vehement opposition - both on the floor of the legislature as well as outside it. When it was finally enacted in March 1872, its provisions allowed the marriage, only on a declaration made by two persons, that they did not profess Hindu, Buddhist, Sikh, Jain, Muslim, Christian, or Parsi religion. The act had no provision as to the dissolution of marriage and its succession.

Then in 1912, Bhupendra Nath Basu introduced the bill seeking amendment in the Act of 1872 to make its provision available to any two Indians intending to marry, irrespective of their religion or faith. This amendment also faced objections from both Hindu and Muslim communities. Some orthodox Muslims viewed that such an amendment will allow Muslims to marry non-Muslims, which is prohibited under personal laws.

Eventually, the amending bill was rejected, and the enactment of 1872 remained in force till 1923. Finally, by the efforts of Hari Singh Gaur, with the support of Sir Yamin Khan of the Muslim League, the Act of 1932 came into force. Now, Hindus could marry under the Special Marriage Act without renouncing their religion and be similarly applicable to Buddhists, Sikhs and, Jains. During this period, only a new enactment regarding succession was introduced, i.e. Indian Succession Act, 1925 (replacing the old law of 1865).

After the promulgation of the constitution in January 1950, the conditions prevalent in the country underwent a significant change. The first step towards the attainment of the objective of a uniform civil code, contemplated under Article 44 of the Constitution, was taken up by introducing a new marriage bill in 1952. It was opposed more particularly by the Muslim community, as the Hindu public opinion was focused on the Hindu code bill. Muslims were already disappointed in not getting protection to their laws under the constitutional provisions. By this time, most of the socially progressive leaders had migrated to Pakistan. But even after this vast opposition, the Special Marriage Act of 1954 was successfully enforced.

Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru faced a lot of conflict from Hindu conservatives, which reflected in the act in the form of compromised provisions. One such provision is the requirement of a notice period before a marriage can be conducted which makes the process more cumbersome. And secondly, if a Hindu, Buddhist, Sikh, or Jain marries outside of these communities, they are no longer considered as a part of the Undivided Family, which means they cannot inherit ancestral property if they marry a Muslim or Christian, etc.

The whole enactment has a basic structure like other marriage laws, but there are also some distinct provisions keeping the secular nature of the enactment intact. The Special Marriage Act has provisions relating to registration of marriage, restitution of conjugal rights and judicial separation, divorce and remarriage, legitimacy of children, alimony and maintenance, custody of children, and the succession provision. The precondition for marriage under the Special Marriage Act is having no living spouse, age limit, sanity, free consent, and no marriage in prohibited relationships.

The whole enactment has a basic structure like other marriage laws, but there are also some distinct provisions keeping the secular nature of the enactment intact. The Special Marriage Act has provisions relating to registration of marriage, restitution of conjugal rights and judicial separation, divorce and remarriage, legitimacy of children, alimony and maintenance, custody of children, and the succession provision. The precondition for marriage under the Special Marriage Act is having no living spouse, age limit, sanity, free consent, and no marriage in prohibited relationships.

The Special Marriage Act provides a mandatory provision for the registration of marriage. The couple has to give a notice in writing to the marriage officer of the district, in which at least one of them has been residing for the last 30 days. The marriage is supposed to be scheduled within three months from the date of the notice. The notice is then published by displaying it in a conspicuous place. In these 30 days, anyone can object to this marriage if it contravenes the basic conditions of marriage. After the solemnization of marriage, the details are recorded on a certificate, which becomes the conclusive evidence of marriage under the Special Marriage Act. The act has further been amended on various occasions.

The provisions of any act must be so implemented that they serve the purpose behind enacting that particular law. Few provisions of the act have been criticized on various occasions as they were enacted with good intentions, but their implementation process created religious chaos.

Firstly, the registration process has been criticized because the requirement of notice before marriage is absent in the Hindu Marriage Act, whereas it's a customary law in Islam. Secondly, the marriage documents, public notices with details of names, addresses, and phone numbers of couples marrying under the Special Marriage Act are splashed on social media calling it 'love jihad'. Another hurdle is the unnecessary interference by marriage officers and police - which is said by courts on multiple occasions - to be neither legal nor is it their job to put procedural roadblocks. There is also the practice of sending a copy of the notice to the residential addresses of the couple intending to marry through the local police station. In 2009, Delhi High Court, while talking about this practice, said: 'the unwarranted disclosure of matrimonial plans is completely whimsical and without the authority of law.'

In the 2018 case of Kuldeep Singh Meena V/S State of Rajasthan, the Rajasthan High Court was also directed to stop the practice of posting intended notice of marriage to the houses of couples. The Delhi High Court also stated that this practice is violative of the right to privacy and the Special Marriage Act is a positive law that was enacted to enable a special form of marriage for any Indian national professing different faiths.

Another provision of the act requires that a notice of intended marriage should be given to the Marriage Officer of the district "where at least one of the parties to the marriage has resided for not less than thirty days immediately preceding the date on which such notice is given." This residence clause makes it hard for couples to evade unwelcome attention.

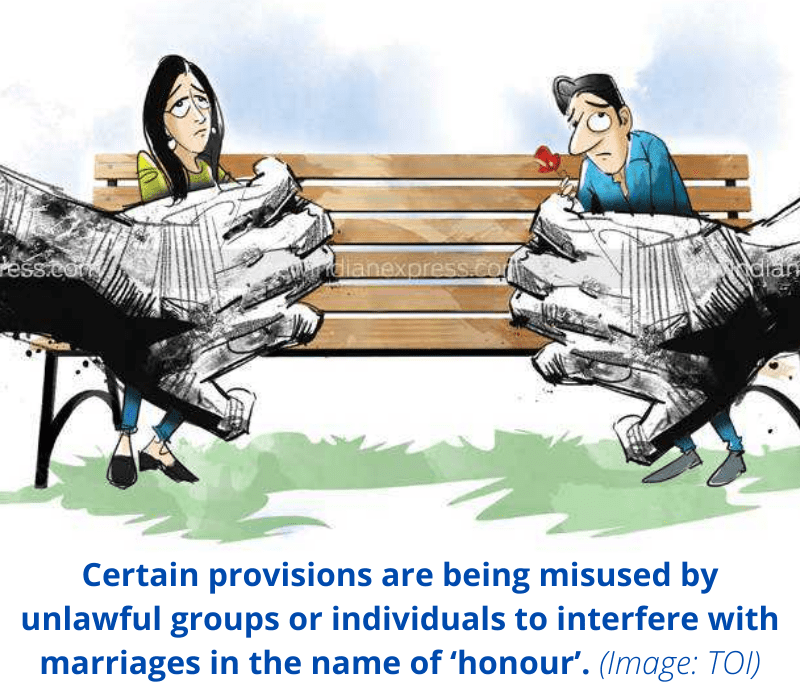

In 2015, an amendment bill was introduced regarding Section 5 of the Special Marriage Act, 1954 (residence clause), as it was being misused by unlawful groups or individuals to interfere with marriages in the name of ‘honour’ and ‘tradition’. Another object of this bill was to curb the crimes committed in the name of honour killing. Along with the Law Commission of India's report titled 'Prevention of Interference with the Freedom of Matrimonial Alliances (in the name of Honour and Tradition): A Suggested Legal Framework, August 2012', the National Commission for Women, in its 2010 draft legislation - 'The Prevention of Crimes in the Name of Honour and Traditions Bill', has also recommended an amendment in the Special Marriage Act, 1954. The recommendation asks for removing the condition of residency of a minimum of thirty days from the date of giving notice of marriage, as this allows certain groups or individuals to interfere with the alliance.

In 2015, an amendment bill was introduced regarding Section 5 of the Special Marriage Act, 1954 (residence clause), as it was being misused by unlawful groups or individuals to interfere with marriages in the name of ‘honour’ and ‘tradition’. Another object of this bill was to curb the crimes committed in the name of honour killing. Along with the Law Commission of India's report titled 'Prevention of Interference with the Freedom of Matrimonial Alliances (in the name of Honour and Tradition): A Suggested Legal Framework, August 2012', the National Commission for Women, in its 2010 draft legislation - 'The Prevention of Crimes in the Name of Honour and Traditions Bill', has also recommended an amendment in the Special Marriage Act, 1954. The recommendation asks for removing the condition of residency of a minimum of thirty days from the date of giving notice of marriage, as this allows certain groups or individuals to interfere with the alliance.

So, the Bill was introduced to amend section 5 of the Special Marriage Act, 1954 to remove the unnecessary requirement of ‘period of notice’ and ‘domicile residence’ to protect the victims or potential victims from the menace of honour killing, but the bill has not been converted into an Act yet.

In September 2020, a petition was filed in the apex court challenging the constitutionality of several provisions of the Special Marriage Act, 1954, which says that giving up the right to privacy to exercise the right to marry infringes the autonomy and dignity of the couples. The provision of notice is said as discriminatory and violative of Article 14 (right to equality) as not given under other personal laws. The disclosure of information of the parties to the marriage is challenged to be violative of the fundamental right to privacy under article 21. The apex court has given notice to the centre and asked to file their reply in this regard.

Many suggestions have been made to render the law to serve its original purpose. The law needs to be redesigned, keeping in mind its original enabling purpose. The invalid objections should not be entertained, the fine should be raised, and punishment needs to be more stringent. There is also a need to take disciplinary action against officials who side with social bullying. In 2018, the Punjab and Haryana High Court, in one of its decision have beautifully stated that "the state is not concerned with the marriage itself, but with the procedure, it adopts which must reflect the mindset of the changing times in a secular nation promoting intercaste marriages, instead of the officialdom raising eyebrows and laying snares and land mines beneath the sacrosanct feet of the Special Marriage Act. 1954".

- Adv. Prachi Patil

pprachipatil19@gmail.com

(The writer is a practicing lawyer at the Pune District Court and the Family Court, Shivajinagar)

Tags: law adv prachi patil legal special marriage act secularism secular legislation Load More Tags

Add Comment