My intention behind the confession scene in Saamana wasn’t just to “try something dramatic.” This confession is the very essence of the entire film. A man has been killed—but why does this confession haunt us? Because Hindurao isn’t confessing to a judge or a crowd—he’s confessing to his own conscience, and to Master, who he thinks is close to him.

Jabbar Sir, in 2013, when the centenary of Indian cinema was celebrated, Sadhana published a special issue on the theme ‘The Film That Deeply Impacted Me’ and recently a book based on that issue has also been published. Actually, we had wanted an article from you for that issue; but during the planning of that issue, you were abroad, so it didn’t happen. Anyway, in that book, I have written about Saamana. Now, there are three reasons why we want to interview you in relation to Saamana. The first and most obvious reason is that I have a deep interest in learning more about Saamana, as it is the film that has influenced me the most. The second reason is that Saamana was released in 1974, which means it has been 40 years now. The third reason- it is your first film, very recently you made a film on Yashwantrao, which means you have been in this field for four decades. The fourth reason is the timing—Lok Sabha elections have taken place, there has been a change of power at the Centre, and state elections are scheduled next week. This Diwali issue is being published against that backdrop. So, I feel it is important to explore in detail the background and future role of Saamana.

Question: So first, tell us this—around 1974, how did the idea of making such a unique and unconventional film like Saamana come about? How did it come to you?

- Directing a film is not that simple. Behind it lies a great deal of time, experience, observation, and many kinds of beliefs. So, I must first tell you a bit about my life before the script of Saamana even came to me. Saamana was my first film as a director, but my journey in the world of art had started much earlier. I had the opportunity to act at the young age of 10 or 12. I completed my schooling in the 1960s. While I was still in school, I got opportunities not only to act in plays but also to direct them. Alongside that, I had the chance to stay at the home of Shriram Pujari Sir in Solapur. (Pujari was a prominent figure in the theatre world at that time.) Living in his house allowed me to closely observe many great personalities from the fields of literature, music, and drama. (From serving them tea to fetching their bathwater!) As a result, I was exposed to the finer nuances of art from some of the greatest minds at a very early age. That’s why the silent play Chafekar, Hadacha Zhunjaar Aahes Tu which I staged during my school days, or the role of Shyam I played in Tujhe Ahe Tujapashi during college, was very well received by audiences.

After coming to Pune, while studying at B.J. Medical College, I got the opportunity to direct several other plays and experiment with unique ideas. For example, Tendulkar’s one-act play Bali or the play Shrimant. During that time, I began to feel a strong urge to do something different. That’s when the search began—and around the same time, Vijay Tendulkar came into my life. I read some of his plays, directed a few, and even acted in some. He gave me a very delicate and sensitive play, Ashi Pakhare Yeti, for the state level drama competition. That play received great acclaim. After that, I got the opportunity to direct the renowned play Ghashiram Kotwal. Ghashiram brought us closer in many ways. Now, before talking about the script of Saamana, one must understand the perspective that people who work with theatre have about cinema. Theatre folk have always felt that they operate in a very limited space on the stage. A play entirely belongs to the playwright. The director merely interprets it. That’s why no director can truly claim, ‘Theatre is my medium.’ And if someone says so, they’re mistaken. Even after directing Ghashiram Kotwal—a play that challenged the very boundaries of the stage, that was bold in form and powerful in content, and earned widespread critical acclaim (which was very serious)—I still firmly believe that Ghashiram Kotwal belongs solely and entirely to Tendulkar!

But that’s not the case with cinema. A film always unfolds through the director’s eyes. In fact, my journey from theatre to Saamana happened alongside Tendulkar. Ever since I began to feel the urge to do something serious and meaningful, it was under Tendulkar’s guidance that I truly shaped myself. Before this significant script of Saamana came to me, perhaps he had already sensed something in me. By then, I had completed my medical studies, and my wife and I had chosen Daund, a town near Pune, to begin our practice. I was a pediatrician, and my wife a gynecologist. My father worked in the railways, so we had chosen Daund with the thought that initially, at least railway employees would consult us. Our practice had started picking up. However, for almost three and a half months, after working the entire day, I would travel to Pune every evening for rehearsals of Ghashiram. While all this was going on, one day Ramdas Phutane came to me. He placed the script of Saamana in front of me and said, "We have to make this film." I said, "Why do you think I can make a film? I don’t even know the language or technique of cinema yet." Ramdas said, "I’ve already discussed this with Tendulkar. Besides, I’ve seen your Ghashiram. I liked it." Ramdas, a drawing teacher and poet, was offering this proposal to someone like me, who was entirely new to the world of cinema. Imagine that—he was new to it, and so was I.

Of course, it was the use of music in Ghashiram, the distinct acting style, the interplay of light and shadow, and the impactful group scenes—these experiments gave Ramdas confidence in me. Even before the script of Saamana came to me, my medical practice in Daund had allowed me to become part of a cross-section of society. Earlier, while working as an intern at Sassoon Hospital, I had closely witnessed poverty, and the experiences in Daund only deepened that understanding. I used to observe movements and social activism from a distance, but with seriousness and thought. However, I never believed that these life experiences alone would qualify me to make a film—but the desire to make one was definitely there. So I asked Ramdas, "You’ve brought me the script of Saamana, but did you speak to Tendulkar about this?" Ramdas replied, "Yes. He said, ‘If Jabbar feels confident, he should do it—because he hasn’t made a film yet.’" Now, this is where you come across the greatness of someone like Tendulkar. He entrusted a script like Saamana, which deals with a highly serious subject, to someone like me who was completely new to cinema. The real credit for the success of Saamana goes to Tendulkar. Not only was the script itself powerful, but the dialogues, the notes in parentheses—all of it carried the story forward with incredible precision.

Along with this, Tendulkar himself had fixed the two main characters in Saamana. One was the chairman of the cooperative sugar factory—Hindurao (played by Nilu Phule), and the other was the schoolteacher, or Master (played by Dr. Shreeram Lagoo). Tendulkar had written both these roles with Nilu Bhau and Dr. Lagoo specifically in mind. When such a grand, powerful, and almost ready-made script was placed before me, I told Ramdas I would read it and get back to him in two days. As promised, after reading the script, I informed him: “Yes, I’m ready to do the film.” Then I went to meet Tendulkar. I told him, “I liked it very much; I’d really like to do it.” As usual, Tendulkar nodded and asked, “Alright, what else did you feel?” I said, “You’ve written this so beautifully that I don’t feel the need to change a single thing. The only challenge now is—how do we bring all of this to the screen?”

Question: What would you like to say about the script and storyline of Saamana?

- Saamana’s story, screenplay, and dialogues—all of it was Tendulkar’s work. In fact, he had written Saamana directly as a screenplay. The plot revolves around the chairman of a cooperative sugar factory and a schoolteacher (Master) who suddenly comes into his life. The chairman is a shrewd and practical man, deeply experienced in political maneuvering, while the Master is someone who had participated in the freedom struggle but became disillusioned after independence. As the Master tries to understand the source of the chairman’s success, he begins to question the darker aspects of that success. In doing so, the narrative attempts to unravel the emotional and moral complexities created by the power structures within the cooperative movement.

Now I will talk about my experience as the director of Saamana. As I’ve said before, the full credit for Saamana goes to Tendulkar—because Saamana wasn’t a story I chose; rather, it was Tendulkar who chose me! Moreover, the main actors in Saamana were also selected by Tendulkar. I didn’t try to steer the story in any other direction; my job was to rigorously and faithfully bring out the socio-political thought behind Tendulkar’s script as deeply as possible. To do that, I decided to understand his thought process more thoroughly. At first, he brushed it off and said, “Did I explain anything to you when we did Ashi Pakhare Yeti? I just let you read it, and you interpreted and directed it the way you wanted. So do the same now.” I replied, “I’ve seen certain things while in Daund, but I still don’t fully grasp the socio-political angle.” He said, “Oh you silly man, life doesn’t end there. There’s more to life beyond that. If you decide to understand it, you will! And even after that, if you get stuck, then ask.”

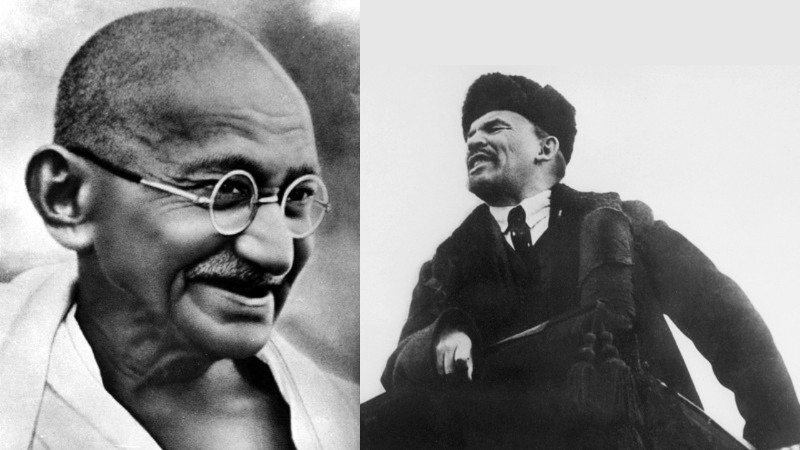

In fact, Tendulkar even told me to rethink things. He had faith in my imagination and my analysis. (Let me share something here: not only Saamana, but ever since we became acquainted until the very end of his life, Tendulkar guided me—whether in resolving public dilemmas or personal struggles. He gave me direction, he supported me. Truly, he was a part of my life!) While working on Saamana, of course the plot was important, but even more important was Tendulkar’s socio-political vision. Whether it was Ghashiram Kotwal or Ashi Pakhare Yeti, Tendulkar always spoke socio-politically through his work. The only difference was that he spoke of different eras and different issues. Through the plot of Saamana, Tendulkar was speaking about the exploitation of the underprivileged masses. While writing Saamana, he had already given a warning to people (like us) around him: "This film is about the powerful centers of authority within the cooperative sector—please, be careful!" The film revolves around two main characters. It is essentially a dialogue between two opposing mindsets that emerged in India after independence in 1947. One of the characters (the Chairman) believed right from the moment of independence that power is the best means to bring about social change.

And the second character (Master) is someone who dedicated his entire life to the freedom movement alongside Gandhi, but who cannot accept the post-independence reality. He constantly feels that the democracy we fought for is no longer visible. The principles of liberty, equality, and justice, which Ambedkar enshrined in the Constitution, are not being realized in actual practice. He feels a deep sorrow over the loss of humanity. Furthermore, Master has taken to alcohol—a substance that numbs and confuses people temporarily—which has trapped him further in his suffering. Moreover, his daughter has died in an accident, which has shattered him completely. So, this is a dialogue between the tragedy of Master's life and the Chairman's exercise of power. Tendulkar has crafted it brilliantly. The Chairman meets Master purely by chance. When they meet for the first time, neither has any idea of the relationship that is about to unfold between them. In their conversation, one (Master) questions the other (the Chairman): "Sir, you have become so successful—what is the secret of your success? Is this the path on which this country will now progress?" As Master poses these questions, he is, in a way, challenging the self-respect of the leader (Chairman). He is confronting someone who carries within him a sense of guilt. And he asks these heart-rending questions not from a public stage, but directly, one on one.

When this film was released, some people remarked that Master and Hindurao are in fact one and the same person. It is as if “Master is Hindurao’s conscience.” But that’s not true. Master is someone enclosed in a shell—he is emotionally broken, while Hindurao is not trapped in any shell. Master is directly questioning Hindurao’s conscience, asking him: "Tell me, where is Maruti Kamble? What happened to him?" And this question—posed by the visionary Tendulkar—is the key point of Saamana. Even today, in 2014, “What happened to Maruti Kamble?” is a question not just unanswered in Maharashtra, but across all of India. That’s why Tendulkar stands tall. His far-sighted approach—his ability to reflect deeply on the present and future of Indian art, culture, and society—took a strong and impactful form in his work. Through Saamana, even though we (Tendulkar and I) were speaking about the moral corruption within the cooperative movement, we also acknowledged the contributions the cooperative sector has made to rural Maharashtra—especially in the fields of education and health.

Without cooperatives, the rise of the Bahujan Samaj across various sectors might not have been possible. We not only recognize this—we are grateful to those who built the cooperative movement. In fact, if you look closely at Saamana—when Hindurao gets arrested, and the next leader turns out to be even worse—it is Master who doesn’t forget to tell him, "Please come back soon." The questions and situations Tendulkar presented in Saamana are truly timeless. Two great artists ensured that these questions were deeply etched in the minds of the audience.

An Excerpt From The Film Saamana

Question: What can you tell us about your experience of directing Saamana?

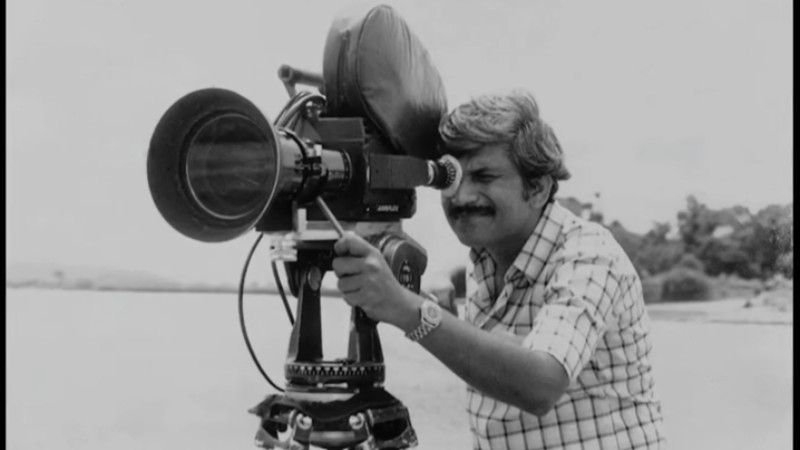

- As I’ve already said, Tendulkar wrote Saamana with specific actors in mind. My real opportunity lay in the filming process. Since there are many cooperative sugar factories in the Kolhapur region, we had initially decided to shoot Saamana there. With the help of Vilas Rakte, we approached some sugar factories for permission—but didn’t receive it. Even after explaining our intentions clearly, they refused. Then we went to Warananagar, to Tatyasaheb Kore. We were welcomed with open arms and given full permission without hesitation. Later, we shot a few parts at Baburao Tanpure’s sugar factory in Rahuri. For the village scenes, we selected the Jamkhed region. For the studio work, we chose Bhalji’s Jayprabha Studio in Kolhapur. Everything was now in front of me—script and cast were ready. All that remained was to proceed technically. But I didn’t know the technical aspects of filmmaking in great detail. At that point, my friend Samar Nakhate came to mind. I told him, “Samar, I don’t understand lenses very well, and I’m not confident with shot division. Buddy, you’ll have to help me.”

Samar was my first teacher in this field. He took on the responsibility with affection. Then came the moment when I had to work directly with great artists like Dr. Lagoo and Nilu Phule.

Honestly, to bring out the full power of Tendulkar’s dialogues, one must explain their finer nuances to the actors. But I was in a fix—how could a junior fellow like me explain things to such legendary performers? So I decided that even if there was a need to explain, I would keep it strictly limited to what was necessary for the camera only. I hadn’t told them how exactly I planned to shoot each shot. I assumed they had already figured out how they would approach their scenes (and that they would manage it). With that faith, I started preparing for the film’s inaugural shoot. The day before the inauguration, Ramdas and I went to Bhalji Pendharkar’s studio in Kolhapur. It was our first meeting with him. He said: “You did Ghashiram, and people have spoken very highly of your work. Your play came to Kolhapur once or twice, but I didn’t get a chance to see it. I heard it has some controversy regarding the Peshwas… Anyway, I’ve heard a lot of praise for your work. So yes, I’ll come to the inauguration.” As we were leaving after thanking him, Bhalji called out, “Oh yes, invite Lata to your inauguration!” At first, I didn’t understand when he said Lata. I said, “Baba”, and he continued, “Yes, Lata’s here. She’s staying for a couple of days. Invite her—she’ll come!” Then he called out, “Lata! Come out for a moment!” And out came Lata Mangeshkar herself! It was utterly unbelievable. I couldn’t believe my eyes.

Then I wished Lata Didi and introduced myself. She said, “Yes, I’ve heard about you. Bal (Hridaynath) often mentions you. Your Ghashiram has music by Bhaskar Chandavarkar, right? He’s a disciple of Pandit Ravi Shankar.” I said to her, “Tomorrow is the inaugural shoot of my first film. It would be wonderful if you could attend.” She replied, “What will I do there?” At that point, Baba said, “Why don’t you start the camera?” And just like that, she agreed! I was stunned. So many remarkable coincidences were coming together for my first film. The next day, Baba and Didi arrived arrived for the inauguration. We were ready to shoot the first scene. Make-up was quick and smooth thanks to Nivrutti Dalvi. Dr. Lagoo arrived wearing his costume and said, “Jabbar, look—I’m ready. From now on, I’m not Dr. Lagoo, I’m your Master. The inaugural shot has whose line?” I said, “It’s Nilu Bhau’s.” He asked, “Did you tell Nilu Bhau how to go about it?” I replied, “No. And I don’t plan to tell either of you anything. I’ll only share how we’ll shoot the scene.” He said, “What do you mean? At least tell us the link between scenes!” I reassured him, “Yes, of course—I’ll explain that.” Samar Nakhate had earlier advised me that if I over-explained, it might become theatrical and chaotic. The camera was set. Chandrakant Mandare did the clap.

Nilu Bhau was ready for the first scene. Lataji looked through the camera. Cameraman Suryakant Lavande asked me to take a look as well—and what I saw was exactly what I wanted. Then came Nilu Bhau’s voice, that iconic deep-throated chant: “Jagdamba... Jagdamba...” Dr. Lagoo, standing beside me, whispered, “Oh my God! Jabbar, we must talk after this shot is done.” I didn’t understand what he meant at that moment. After the ceremony, once the guests had left, we sat in the makeup room. Dr. Lagoo said, “Jabbar, did you notice? My voice is in the same lower register as Nilu Bhau’s. If both of us continue with similar deep-pitched voices, they’ll constantly clash on screen—it will be very jarring.” I said, “You're right, but the difference in pitch should help.” He replied, “Not quite. I’ll need to think of something else. I didn’t consult Nilu Bhau on purpose. I wanted to see what naturally emerged from him.” At that moment, I learned something vital—how one intelligent actor understands and respects another.

Then he spoke in a new pitch—similar to that of Acharya Bhagwat. It perfectly complemented Nilu Bhau’s tone and created a beautiful contrast. When he did that voice—a tone that could jolt Nilu Bhau’s character into awareness—both Nilu Bhau and I were thrilled. “Fantastic, Doctor! Now this will be fun. Let’s move ahead!” Nilu Bhau said. That was the moment I realized that Tendulkar’s ideas can now truly take root. Because what came naturally was what would carry forward the film’s message. Even though Dr. Lagoo’s character came second in terms of appearance, the pitch he adopted was brilliant. And the credit is entirely his. The shooting of Saamana went on for three months, but throughout the entire shoot, I never once had to direct those two actors in terms of performance. They brought the script and Tendulkar’s intentions to life flawlessly. Their portrayal throughout the film was simply great. And one more name that deserves equal praise is cameraman Suryakant Lavande.

His lighting work in black and white, and the way he executed shots, was outstanding. He stepped outside the conventions of commercial cinema and shot Saamana wonderfully.

Let me share another interesting moment from the direction of Saamana. There’s a scene where Hindurao confesses to Master about the murder of Maruti Kamble. At that time, Nilu Bhau said, “Jabbar, this is such a long scene. How am I going to memorize all that dialogue? I told him, “It’s alright if the words come a bit out of order, Nilu Bhau—but you have to speak from your heart, from what’s built up inside you.” That scene, which runs for four and a half minutes, took us three hours to shoot. It needed several rehearsals with Nilu Bhau to get it right. Nilu Bhau’s confession scene in Saamana always reminds me of Dilip Kumar’s confession scene in the film Footpath. Let me clarify—my intention behind the confession scene in Saamana wasn’t just to “try something dramatic.” This confession is the very essence of the entire film. A man has been killed—but why does this confession haunt us? Because Hindurao isn’t confessing to a judge or a crowd—he’s confessing to his own conscience, and to Master, who he thinks is close to him. After the entire confession, Hindurao tells Master: “Master, shall I tell you something? My only intention behind this was the welfare of the community. But Maruti Kamble stood in my way, so I had to get rid of him.”

This is a confession from a political leader. And why does it haunt us so deeply? Because while we hear it, it brings to mind the many political leaders around us. And we wonder, “Why don’t they confess to us just once, like this?” Murders like this happen elsewhere too. But what sets Tendulkar apart in Saamana is that he depicts the moral and social degradation behind the crime. Through Hindurao’s confession, Tendulkar pulls our attention beyond mere economic corruption, towards moral corruption. Even today, most analysts focus only on economic corruption. But we know that strict laws can deal with that. The main question is how does one put an end to the rising tide of moral corruption in our society. This is where Tendulkar’s brilliance shines through in Saamana. By making Master draw out a confession from a morally corrupt man like Hindurao, Tendulkar makes a powerful plea—that corrupt leaders should turn inward, should self-reflect. But as of today, the only punishment for moral corruption seems to be self-examination—and nothing more.

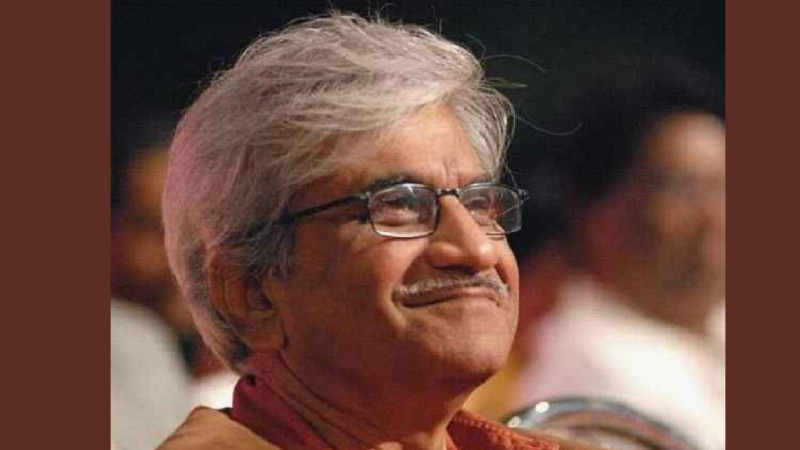

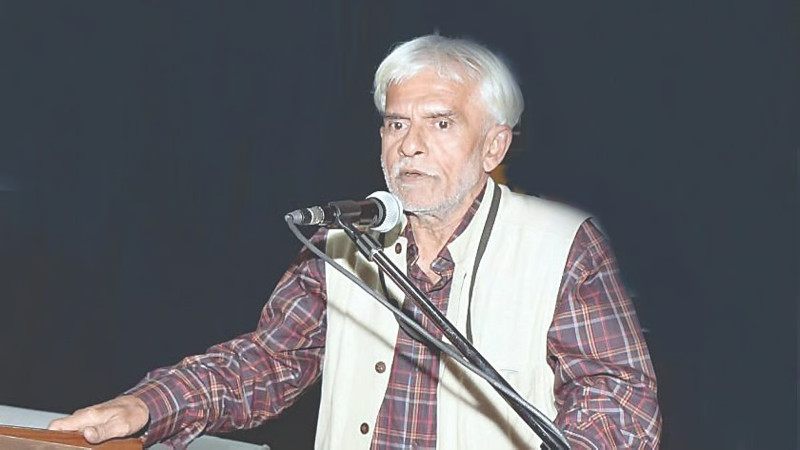

- Dr. Jabbar Patel in conversation with Vinod Shirsath

Translation by Rahee Dahake

The interview was originally published in Marathi in Weekly Sadhana Issue dated 25 October 2014

‘सामना’चे दिग्दर्शक जब्बार पटेल

Read Part 2 Of This Interview Here.

Tags: Dr Jabbar Patel Jabbar Patel Saamana Samna Samna the film Samna the movie Samna 1975 vinod shirsath सामना सामना चित्रपट सामना 1975 जब्बार पटेल डॉ. जब्बार पटेल विनोद शिरसाठ राजकीय सिनेमा विजय तेंडुलकर श्रीराम लागू लता मंगेशकर रामदास फुटाणे निळू फुले nilu phule ramdas phutane shreeram lagoo lata mangeshkar ghayal mi harini kunachya khandyavar junache ojhe maruti kamble Load More Tags

Add Comment