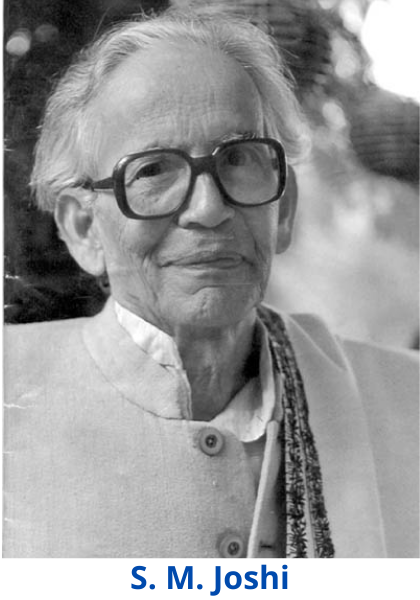

Shridhar Mahadev Joshi (S M Joshi) and others V/S The State of Maharashtra (Bombay High Court 07/12/1976)

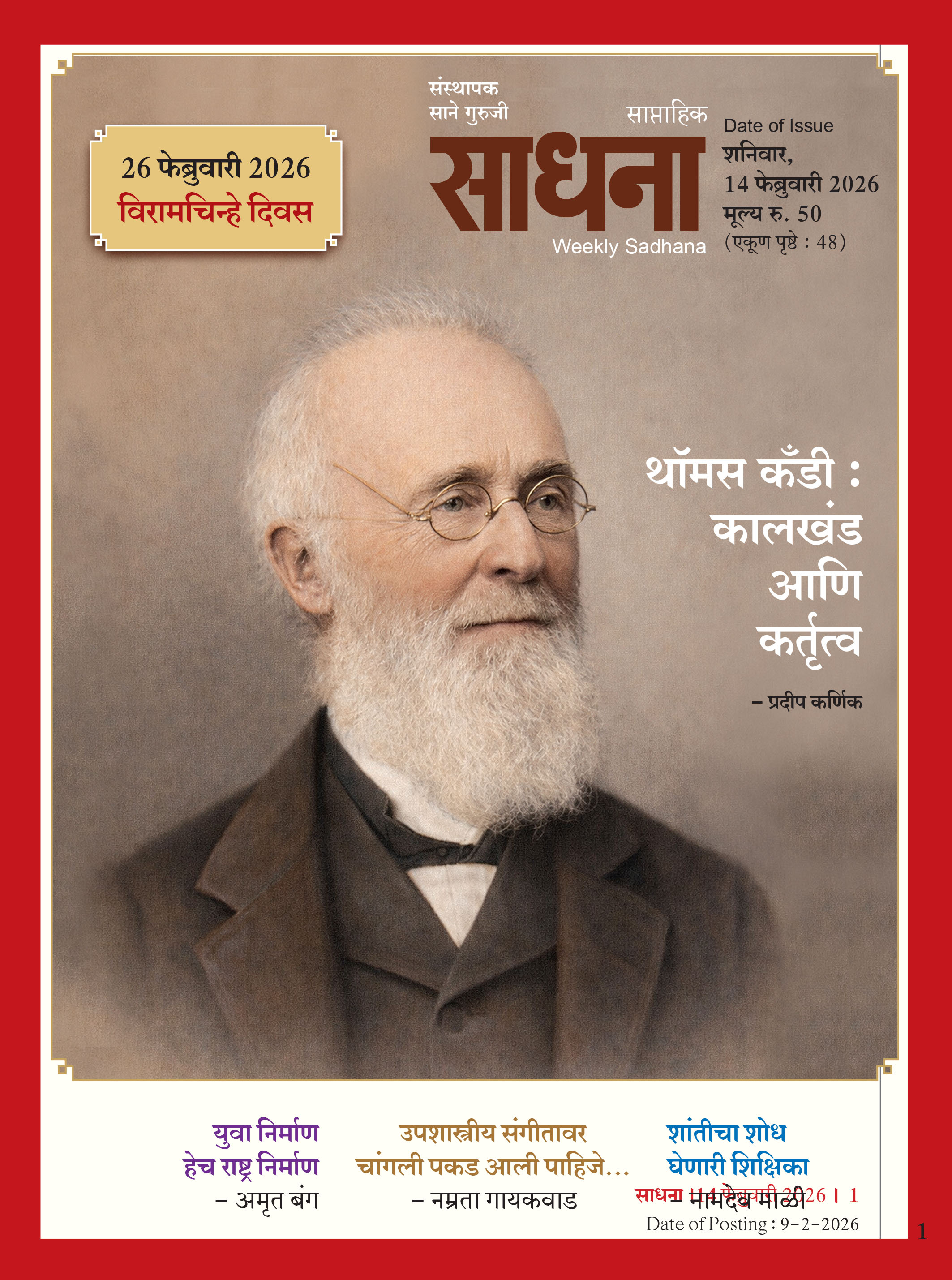

This was the writ petition filed by Shri Shridhar Mahadev Joshi (S M Joshi) - the then managing trustee of Sadhana trust, Shri Dattatraya Ganpat Dengle - keeper of Sadhana press, and Shri Yadunath Dattatraya Thatte - editor, printer, and publisher of Sadhana. The petition sought to challenge and quash the penalties of forfeiture of particular issues of Sadhana and closure of Sadhana press under the Defence and Internal Security of India rules, 1971.

The petitioners claimed that "Sadhana pursues responsible journalism and objectivity, probity and self-imposed restrain and high ethical standards and is miles away from the yellow journalism". On the proclamation of emergency, pre-censorship was imposed too, however, trustees of Sadhana decided to continue printing in consonance with the philosophy of Late Sane Guruji that “May India attain socialism without violence (blood-shed) and may socialism with individual freedom flower in the country”.

The petitioners claimed that "Sadhana pursues responsible journalism and objectivity, probity and self-imposed restrain and high ethical standards and is miles away from the yellow journalism". On the proclamation of emergency, pre-censorship was imposed too, however, trustees of Sadhana decided to continue printing in consonance with the philosophy of Late Sane Guruji that “May India attain socialism without violence (blood-shed) and may socialism with individual freedom flower in the country”.

This way, Sadhana weekly, and many other prominent magazines and newspapers raised their voices against the curtailment of their freedom of expression during an emergency. The media, since its emergence, has gone through lots of ups and downs.

When the constitution was being drafted, the question was raised about whether a separate provision should be made for the freedom of the press. To this, Dr. B R Ambedkar answered, saying "The press is merely another way of stating by an individual or citizen. The press has no special right which is not to be exercised by the citizen in his capacity. The editor of the press or manager are all citizens, and therefore when they chose to write in the newspaper, they are merely exercising their right of expression and in my judgment, no special mention is necessary of freedom of the press at all."

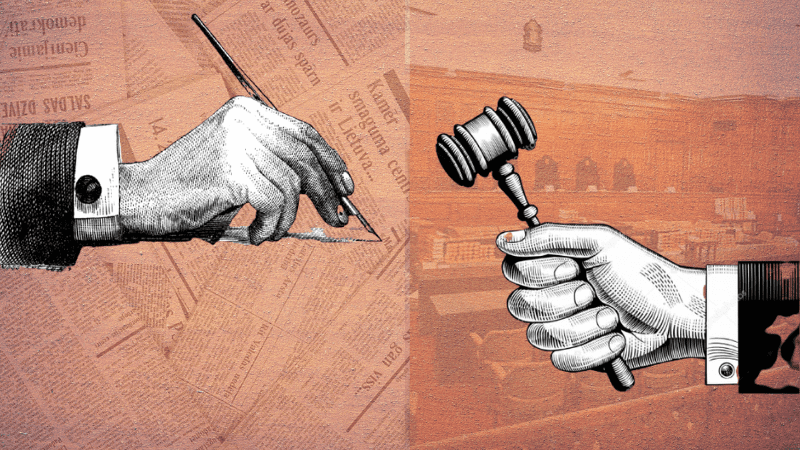

So, though freedom of the press is not specifically mentioned in the constitution, it has been time and again recognized under the freedom of expression. The concern is the extent to which freedom can be exercised and how much control can be imposed.

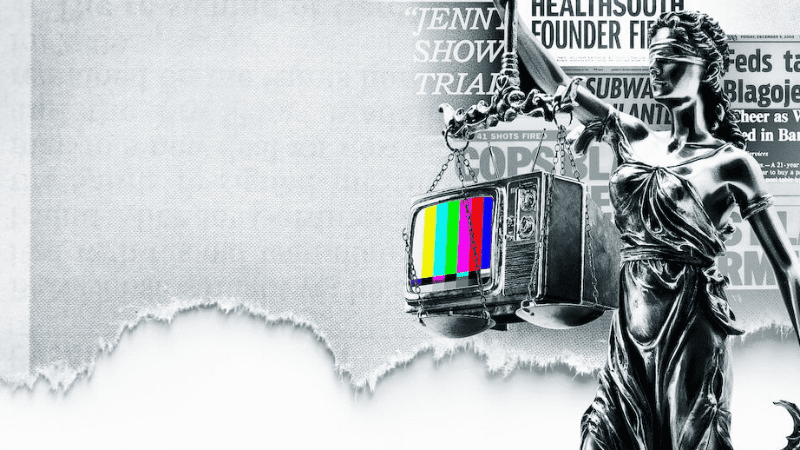

The topic of freedom of the press is always in flames. Recently, the country saw an uproar and showed its grave concern in the sensational case of the late actor, Sushant Singh Rajput. The issue was about the investigation and alleged mishandling of his unnatural death. The media has published information based on mere assumptions and suspicion about the line of investigation by the official agencies to vigorously report on the issue on a day-to-day basis, and comment on the evidence without the factual matrix.

The media's method of conducting a parallel investigation and trial has affected many fronts. It has also raised many questions regarding the freedom of the press, fair trial, right of representation of the accused, whether media trial amounts to contempt of court, and laws & regulations governing media trial.

A petition has been filed in the Bombay High Court, which raises grievance about the media's reportage on the death of Sushant Singh Rajput. It has suggested that the guidelines issued by the court regulate the print media or broadcast media without curtailing the freedom of the press. This change in the role of media is not sudden, and the way it changed can be answered by understanding the journey of the media since its emergence till today, including the media during the emergency period.

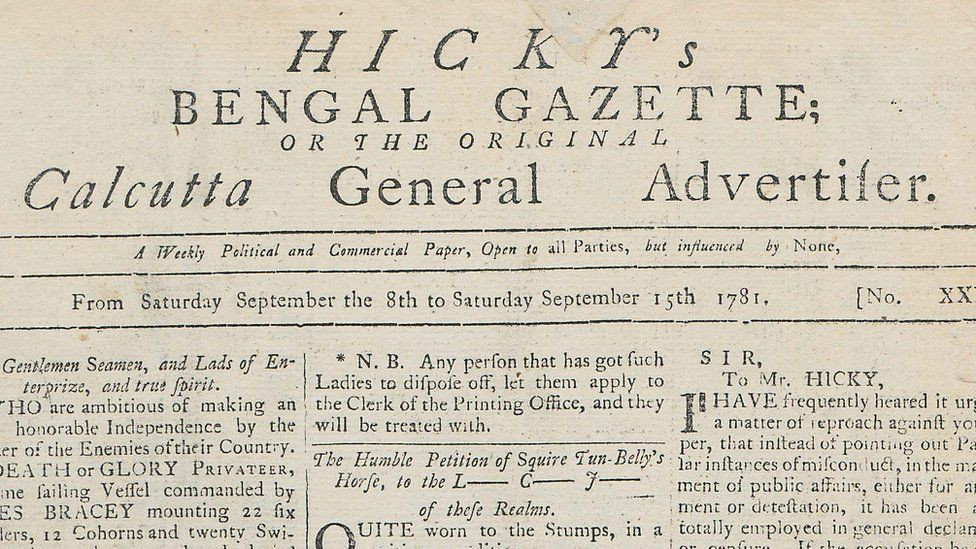

Media in India has a long history, springing from the colonial past in the second half of the 18th century. It started as a private enterprise owned by an Englishman during the East India company's regime, so the content of the newspaper was principally about white man's affairs.

In January 1780, the first newspaper, in India - 'The Bengal Gazette' was started by James Agustus Hicky. But it was closed down soon after due to its outspoken criticism of the Government. Indianisation of the press was brought forward by Raja Ram Mohan Roy, followed by Mahadev Govind Ranade, Dadabhai Navroji, and Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar.

In January 1780, the first newspaper, in India - 'The Bengal Gazette' was started by James Agustus Hicky. But it was closed down soon after due to its outspoken criticism of the Government. Indianisation of the press was brought forward by Raja Ram Mohan Roy, followed by Mahadev Govind Ranade, Dadabhai Navroji, and Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar.

The press in those days put a heroic effort to promote the cause of Independence. The vernacular press also played an indispensable role in strengthening popular sentiments. Right from the early 19th century, defense of civil liberties, including freedom of the press, had been on the national agenda. The British Government had introduced various enactments to regulate the press media as they were spreading awareness regarding the freedom movement.

The Censorship of Press Act, 1799 came first, which was introduced in the anticipation of the French invasion of India. Then came The Licensing Regulations, 1823, according to which starting or using a press without a license was a penal offense. These regulations were chiefly against the Indian newspapers. It was followed by the Press Act, 1835, which became the liberator of the Indian Press. Then again came the Licensing Act, 1857, which imposed the licensing restrictions. The 1835's act was replaced by the Registration Act, 1872, which was mainly regulatory.

The other legislation was the Vernacular Press Act, 1878. It was called the 'gaging act' as it used to discriminate between the English and Vernacular Press. There was no right of appeal provided under this act. Some penal provisions were also introduced through The Indian Penal Code, 1860. Section 124A, along with section 153A, made it a criminal offense for anyone to bring into contempt of the Government of India or to create hatred among different classes.

After the Incitement of Offences Act, 1908 came the Indian Press Act, 1910, which imposed unreasonable conditions on the working of the press. In 1921, these acts were repealed on the recommendations of the press committee chaired by Tej Bahadur Sapru.

During the 1950s and 1960s, that is after independence, the press was perceived as an instrument of development and transformation in the developing country. The then Prime Minister, Pandit Jawaharlal Nehru, had a liberal outlook and staunch belief in the need for freedom of the press in a democratic setup. It gave the press sufficient flexibility.

When the emergency was declared in 1961, there was no strict censorship on the press. But he was also forced to curb the press to check the newspaper reports with communal overtones. Thus, the Press Objectionable Act was passed in 1971. But it was not implemented vigorously due to the large protest from the journalists.

A press commission was also formed to look into the issue of the press in India, which gave its report in 1954. The commission, in its report, came across yellow journalism - which means no legitimate, well-researched news, and instead, using eye-catching headlines for increasing sales. The commission recommended setting up of a press council which was implemented by constituting the first press council of India in 1966.

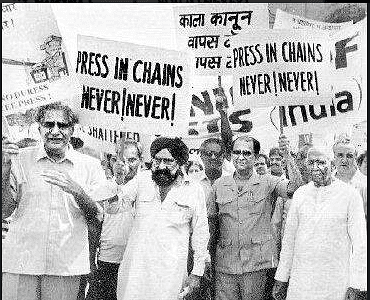

Contrary to 1961, huge censorship was imposed on the press during the emergency of 1975. Monopoly and Restrictive Trade Practices (MRTP) Act was introduced to limit the amount of newsprint used by the larger English medium dailies and to regulate their circulation. With freedom comes the responsibility to uphold that freedom under all circumstances. Sadly, during the Emergency, most of India’s domestic dailies gave up the battle for press freedom after the initial protest.

For the first two days, there was some semblance of opposition from some sections of the print media. Blank editorials appeared as a gesture of protest. Official threats caused these to vanish in no time. Consequently, there was, by and large, a meek submission to the drastic curtailment of Press and personal freedoms. It was the first time after Independence that pre-censorship on the Press had been imposed on the Indian Press. It implied the government would decide the news and information to be disseminated by the newspapers on all policies, programs, and even individuals.

For the first two days, there was some semblance of opposition from some sections of the print media. Blank editorials appeared as a gesture of protest. Official threats caused these to vanish in no time. Consequently, there was, by and large, a meek submission to the drastic curtailment of Press and personal freedoms. It was the first time after Independence that pre-censorship on the Press had been imposed on the Indian Press. It implied the government would decide the news and information to be disseminated by the newspapers on all policies, programs, and even individuals.

So, instead of the editors and journalists playing their role as independent watchdogs of the democratic system, the government became the ‘gatekeeper’ of all news.

The government issued Central Censorship Order and Guidelines for the Press in the Emergency period. Newspapers, magazines, films, radio, television, and phonograph records in India were primarily an urban phenomenon in 1975. Yet, they were powerful because their "leadership" was the intelligentsia, the middle class, the youth, the unionized workforce, and the military-technocratic-bureaucratic elite.

"Where the mind is without fear and the head is held high, where knowledge is free.....

Where the world has not been broken up into fragments by narrow domestic walls.....

Where words come out from the depth of truth, where tireless striving stretches its arms toward perfection......

Where the clear stream of reason has not lost its way into the dreary desert sand of dead habit.......

Where the mind is led forward by thee into ever-widening thought and action.......

In to that heaven of freedom, my father, LET MY COUNTRY AWAKE! "

This poem of Rabindranath Tagore was reproduced in a newspaper to show protest against the emergency. It is well applicable in all contexts and to the media of all eras.

- Adv Prachi Patil

pprachipatil19@gmail.com

(The writer is a practicing lawyer at the Pune District Court and the Family Court, Shivajinagar)

Following parts published in this series:

Part 2: Media Trial - Antithesis of Freedom of Speech and Expression

Part 3: The Dichotomy of Free press vs. Fair trial

Part 4: Rule Of Law vs. Rule Of Noise

Tags: law legal media press freedom adv prachi patil emergency media trial journalism series media trial series Load More Tags

Add Comment