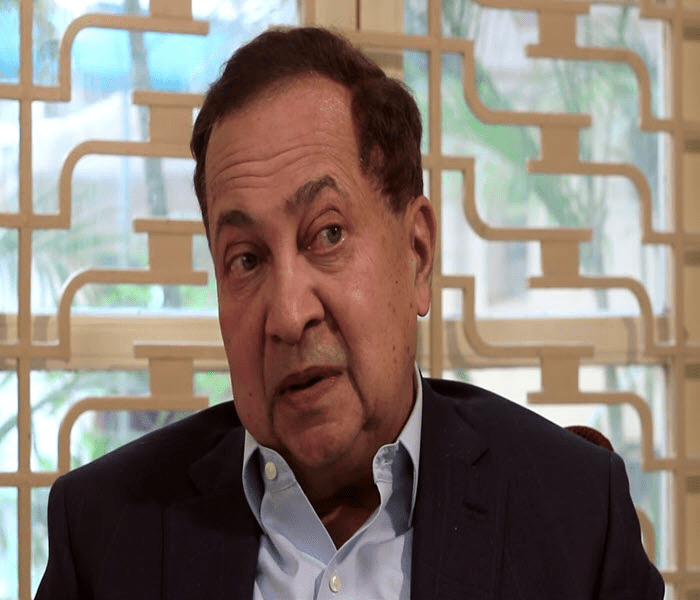

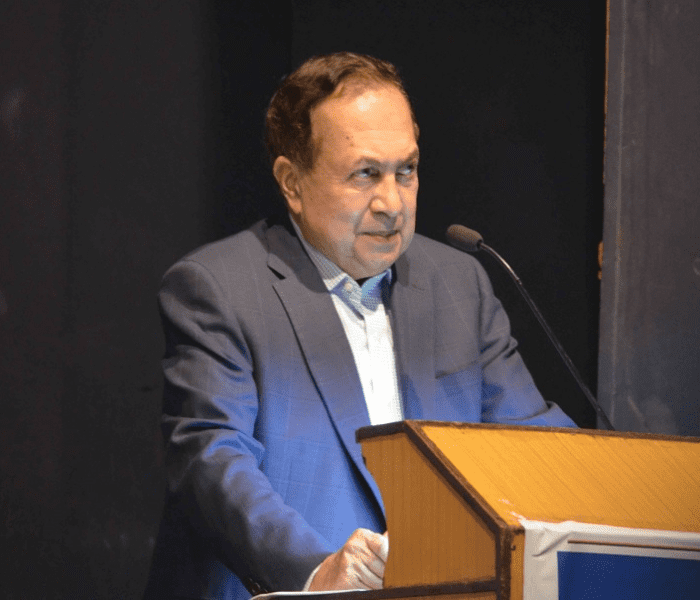

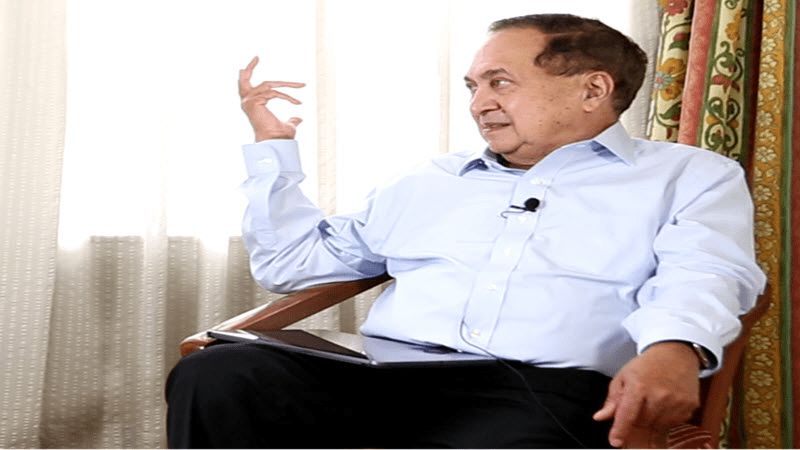

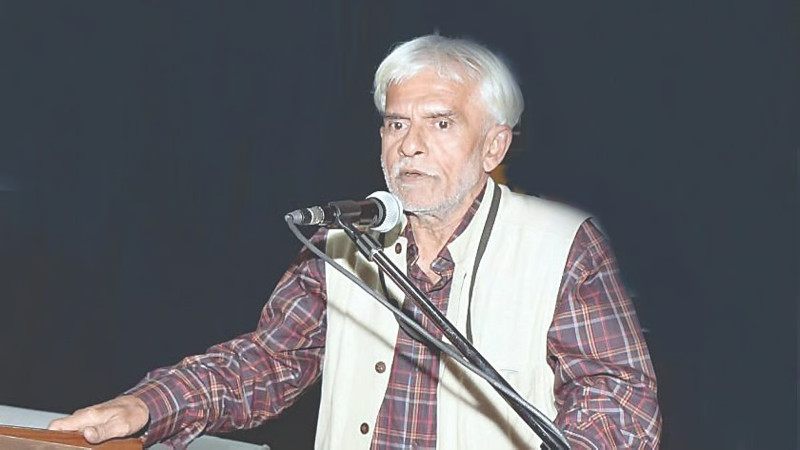

(N. Ram was in Pune to deliver the first Dr. Narendra Dabholkar Memorial Lecture on 20th August 2019. The following article is the second part of his lecture. Mr. Ram is the Chairman of The Hindu publishing group. Previously, he was the editor of The Hindu for 9 years and the editor of Frontline for 12 years.)

The second big question I wish to address is probably at the top of the minds of most people who are here: What kind of society are we building today? What is our idea of India and has that idea changed for most Indians?

This challenging question has come to the fore at a time the party of the Hindu Right, led by an RSS-pracharak-turned-charismatic-mass-political-leader, has won a renewed and stronger mandate and is actively consolidating its power at the Centre. This party has an improved majority of its own, with flanking support from a family of militant Hindutva organizations that used to be regarded as belonging to the ‘fringe’. It is no secret that this new dispensation is armed with an ideology and a socio-political program that are at odds with what we have been accustomed to for most of India’s independent career. It is important to realize that when the RSS supremo, its sarsangchalak, proclaims that India is a Hindu nation and Hindutva is its identity, striking a blow at the secular concept of Indian citizenship and at the Constitution itself, he speaks for the constellation as a whole. He speaks for the entire Sangh Parivar, comprising the party of government as well as the so-called fringe outfits, with the RSS acting as the ideological fulcrum. Let no one have any doubts about this.

Communalism as a political mobilization strategy has made disturbing progress over the past several years, feeding on the weaknesses, the vices, the corruption, the anti-people policies, and the sheer incompetence of preceding governments. What is clear from the history of India over the past century and a half is that a wrong or unprincipled understanding of the problem of communalism in society and politics can lead to very tragic outcomes for large numbers of people.

Communalism in the South Asian sense is, according to the historian Sarvapalli Gopal, “unknown almost anywhere else in the world” and of relatively recent origin. Combated through the active and sustained practice of what the Constitution has mandated in independent India, it could have been marginalized or at least contained. Yet it has been able, on account of a complexity of factors, to capture hearts and minds and occupy the political center stage in the second decade of the 21st century.

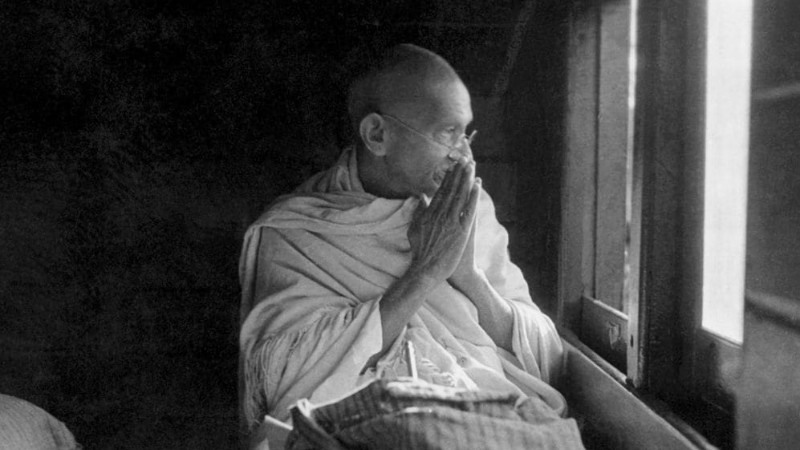

The question that arises is whether this process in society is temporary or is going to be long-lasting. At moments like the present, the apparent absence of capabilities within the political and constitutional system to keep religious majoritarianism at bay dispirits those who believe in secular democracy and modern civil society. But surely it won’t do to accept any assessment or conclusion that suggests the inevitability of the triumph of an authoritarian majoritarianism over the progressive values of our freedom struggle, values that are embedded in our democratic and secular Constitution. I would like to think that given the strengths of India’s composite culture, its civilizational reserves, the wisdom of ordinary folk, the process being described above cannot be long-lasting. It is certainly not irreversible.

It is fashionable today to decry secularism as a tired, formulaic, hack concept and even some liberal journalists and other members of a supposedly liberal intelligentsia seem to have embraced the fashion. I think now is the time to take a clear-sighted stand on this question. Many things are going for secularism in India, among them our history, our freedom struggle, and our Constitution. But very often when Indians debate secularism, at the intellectual or political level, the issue tends to get blurred or confused.

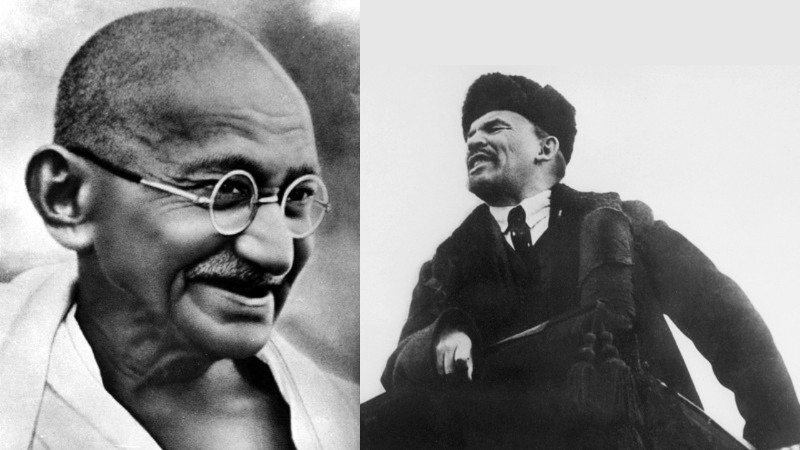

The typical definition on offer in the Indian debate on secularism is sarva dharma samabhava (equal respect for all faiths) or sarva dharma sadbhaava (good feelings towards all faiths). Over time, various leaders, including the philosopher-statesman Sarvepalli Radhakrishnan, have offered interpretations of secularism that suggest that in the Indian context it has a rather special, if not unique, meaning. Sometimes it is defined as religious tolerance and catholicity of outlook. Sometimes the famous statement of Swami Vivekananda in his Chicago address of 1893, “We believe not only in universal toleration, but we accept all religions as true,” is cited as the core of Indian secularism.

Such attempts at definition and clarification of a key concept in modern Indian history may have their advantages and application in particular gatherings or contexts since they have the progressive effect of countering bigotry, intolerance, and fundamentalism in social life and communalism as a phenomenon. But intellectually and politically, they won't do as an interpretation of secularism and what it demands.

To put it differently, sarva dharma samabhava or sadbhava is a necessary but insufficient condition for the flourishing of secularism in India. Let me suggest why.

Secularism as a concept that must be put to work all the time consists of two robust principles. The first is that people belonging to all faiths and social sections and to both sexes are absolutely equal before the Constitution, the law, and the state. There shall be no discrimination against anyone on grounds of religion, caste, race, ethnicity, language, and gender. This is what the Constitution of India mandates through several provisions. The constitutional guarantee of the special rights of religious and linguistic minorities is an extension of this equality-and-fairness principle. The abolition of untouchability and the exceptions to the non-discrimination rule made to safeguard compensatory discrimination in favour of the Scheduled Castes, the Scheduled Tribes, and also the socially and educationally backward classes are meant as devices to secure the integration of historically disadvantaged groups of people and their access to fair equality of opportunity.

Secularism as the equality-and-fairness principle must be based on justice if it is to survive and flourish. The unmet demand for justice in India has many dimensions – the constitutional-political, the social, the economic, gender, and so on. Discrimination and the denial of elementary justice in these dimensions weaken and sap the practice of secularism. Revivalism, traditionalist attitudes to women, caste, and social hierarchy, belief in Sanatana Dharma and Manu Dharma work against secularism primarily by denying justice to the victim sections, the losers, in the population.

Hindu Rashtra ideology flagrantly denies this equality-fairness-and-justice principle. It does this crudely through spraying anti-Muslim venom into society and, at a more sophisticated level, by advocating the value of ‘positive secularism’. Positive secularism as a political mobilization strategy needs the disguise of nationalism, or rather pseudo-nationalism, to gain legitimacy. Defining many-hued Indian civilization, and all Indians, as ‘Hindu’ (in a ‘cultural sense’), legitimizing Hindutva, pushing the validity of majoritarianism as an imperative of electoral democracy, and calling for an authoritarian ‘national unity’ and ‘patriotism’ on this reactionary and deeply divisive basis is what pseudo-nationalism seeks to achieve for the communalists.

But the second principle of secularism is even more important in the present context where major institutions are sought to be restructured. Although constitutionally and legally mandated, this principle is honored flagrantly in the breach. This principle is that religion shall not be inducted into politics, that it shall not be exploited for political gain. The Constituent Assembly adopted a resolution in 1948 mandating this, and both the electoral and criminal laws have provisions in support of the principle. On March 11, 1994, a nine-member bench of the Supreme Court of India full-throatily upheld the principle in its judgment in what has come to be known as the Bommai case.

It is important to recognize that communalism in India is of diverse origin and content. It is not the monopoly of any one community. There is majority communalism and minority communalism and they feed on each other. Jihadism, which used to be regarded as a fringe phenomenon, has come to center stage from time to time in recent decades. Often employing terror as a weapon, it has taken a heavy toll of human lives, livelihood, and welfare. And what is more, it strengthens the ideology of the Hindu Right.

The fight against communalism and religious fundamentalism, fanaticism, and extremism cannot be successful unless it is deeply rooted in reason and unless a scientific temper can be developed among the mass of the population. Communalism feeds on the most reactionary and harmful forms of superstition, obscurantism, pseudo-science, charlatanism, quackery, and hard-core criminality in religious guise. Even the Indian Science Congress has fallen victim to these obscurantist elements. It was not for nothing that Nobel laureate Professor Venkatraman Ramakrishnan went on record to say: “I attended one day and very little science was discussed. It was a circus. I find that it’s an organization where very little science is discussed. I will never attend another science congress in my life.” I don’t have to elaborate on the critical importance of fighting obscurantism, superstition, and anti-science because this is the aspect of the challenge that Dr. Dabholkar’s writings and life-work addressed tirelessly, effectively, and heroically.

(Part 1 of the lecture can be found here, and part 3 of the lecture can be read here.)

Tags: The Hindu Narendra Dabholkar Three Challenges Facing Contemporary India Memorial Lecture नरेंद्र दाभोलकर स्मृतिव्याख्यान द हिंदू भाषण Speech इंग्लिश Load More Tags

Add Comment