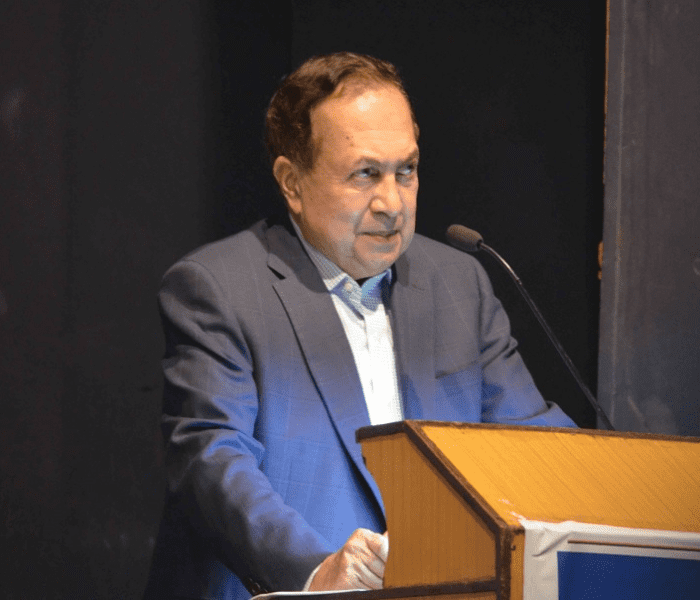

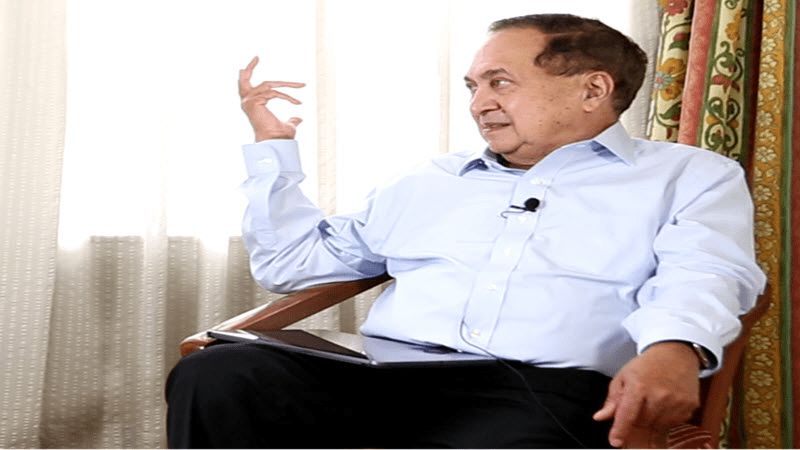

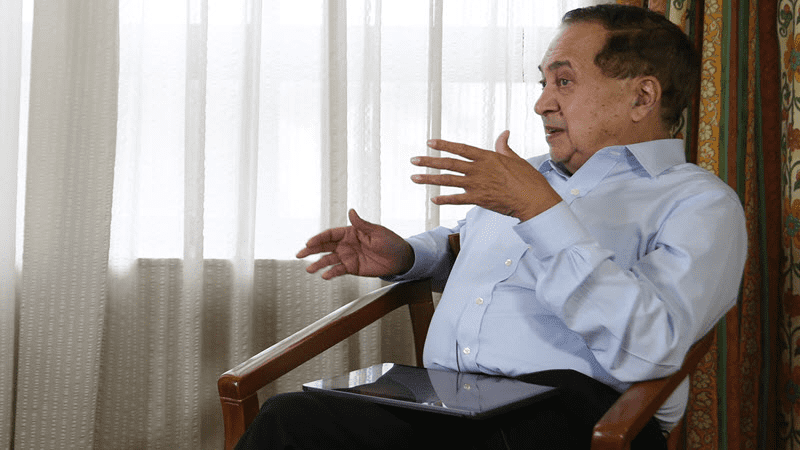

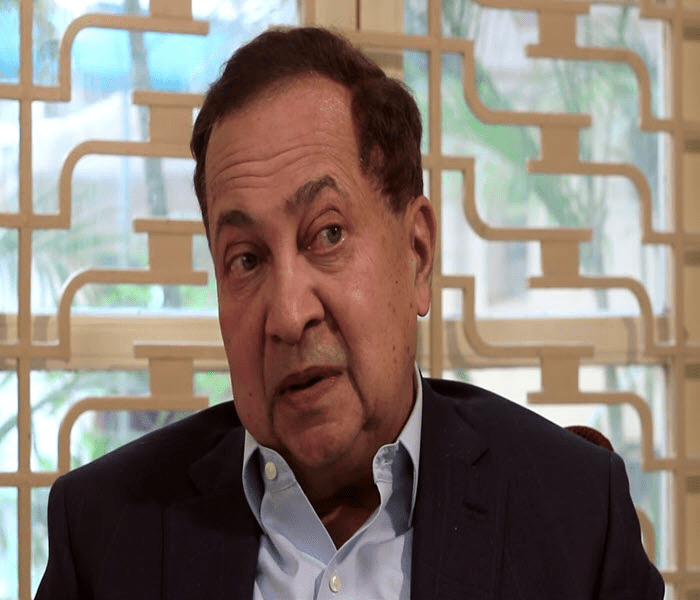

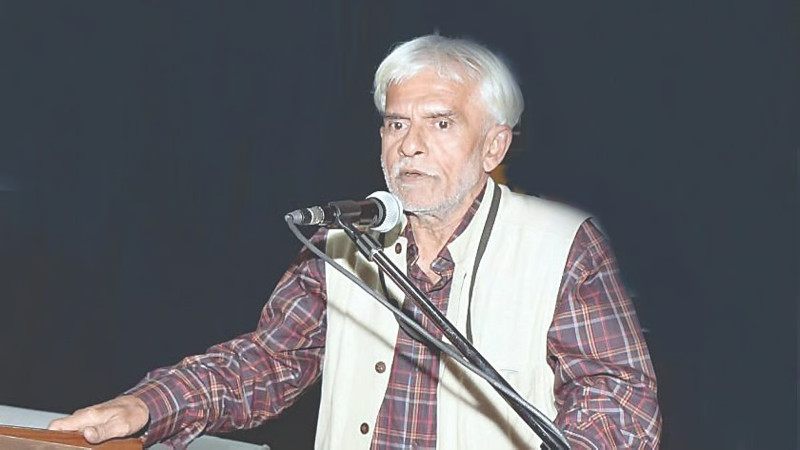

(N. Ram was in Pune to deliver the first Dr. Narendra Dabholkar Memorial Lecture on 20th August 2019. The following article is the third part of his lecture. Mr. Ram is the Chairman of The Hindu publishing group. Previously, he was the editor of The Hindu for 9 years and the editor of Frontline for 12 years.)

It is obvious that any campaign that makes a case for reason, science, democracy, the rule of law, and social and economic justice must give high priority to freedom of speech and expression and freedom of the press and, by extension, of the news media.

Article 19(1)(a) of the Constitution of India, which was adopted in 1950, guarantees “freedom of speech and expression” as a fundamental right. This right, hard-won in the freedom struggle against a highly repressive and censorious British Raj, is deemed to be unamendable thanks to the ‘basic structure’ doctrine propounded by the Supreme Court.

Freedom of the press is not explicitly mentioned by the Indian Constitution but the Supreme Court of India has, through judicial interpretation, read it into Article 19. It has held that freedom of the press is a combination of two freedoms – Article 19(1)(a), ‘the freedom of speech and expression’, and Article 19(1)(g), ‘the freedom to practice any profession, or to carry on any occupation, trade or business’. The first is the principal component.

Unfortunately, freedom of speech and expression is hemmed in, and to a significant extent undone, by Article 19(2). This provides for restrictions on the fundamental right prescribed by law – some reasonable, most not. Notable among the unreasonable restrictions that remain on the statute book or in practice is the law of criminal defamation, the undefined power of contempt of court, uncodified legislative privilege, the law of sedition (124A of the Indian Penal Code), other illiberal provisions of the IPC (especially 153A), the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act, and other draconian laws enacted in the name of fighting extremism and terrorism.

Today, it is clear that freedom of the press and, more generally, freedom of speech and expression in India are under pressure and, in several cases, under assault. I will come to direct and violent assaults on freedom of the news media in a minute. But ordinary citizens find their fundamental right to freedom of speech and expression diminished, hampered, and constrained by an overarching climate of fear and intimidation. Citizens making innocuous Facebook posts have been arrested and even when they are given bail find themselves facing criminal charges. A total information blackout and Internet shutdown was imposed, in flagrant violation of Article 19 of the Indian Constitution, on the entire population of the former State of Jammu & Kashmir for a prolonged period, without the government even bothering to offer a serious explanation for why such extreme measures had been called for.

In 2018 India ranked 138th from the bottom among 180 countries and territories figuring in the annual World Press Freedom Index[i] compiled by Reporters sans frontières (RSF), a Paris-based independent organization that dedicates itself to freedom of information. In a comparative reckoning where the worst score was 88.87 and the best 7.63, India’s score was 43.24 – the same as Pakistan’s.

But the bad news does not stop here. The Committee to Protect Journalists (CPJ) has, after careful inquiry and strict verification, documented the work-related killing of 1350 journalists worldwide, including 50 in India, since 1992. That was the year the New York-based independent non-profit organization, founded in 1981 to defend journalists worldwide from danger and the fear of reprisal, began to compile data on journalist fatalities across the world. Of the 50 killed in India since 1992, 35 were murdered ‘in retribution for, or to prevent, news coverage or commentary’, and the remaining 15 lost their lives while on ‘dangerous assignments’ or in crossfire. As the respected Editor of Sadhana, Dr. Dabholkar figures in the list of journalists murdered. A breakdown of the subjects covered by the murdered Indian journalists is revealing: politics (20); corruption (21); crime (11); human rights (8); culture (4); business (3); and war (1). (These numbers add up to more than the total shown, because many of the targeted journalists had covered more than one subject.)

While no correlation can be detected between the murders and the governments in place in the States and at the center between 1992 and 2018, it is significant that the overwhelming majority of the murders were committed against journalists reporting or investigating politics, corruption. However, the CPJ’s research does suggest that communal and other forms of divisive politics and social polarization across India have made the situation worse: ten journalists were murdered across India over the decade beginning May 2004, but the four years beginning May 2014 have already seen the death toll rise by another 12. And it is not as though only defenseless local reporters working in remote locations have been targeted by the killers; experienced journalists writing against communalism or investigating corruption and working for influential news media are also part of the rising toll, which suggests that journalist murders might be going through a process of deadly normalization in the system.

A special report by CPJ on India found that most of the murdered journalists were small-town reporters who faced much greater risk to their lives and limbs than their big-city counterparts working for larger media organizations, that more than half of them had reported regularly on corruption, and that ‘a lack of media solidarity’ had added to the dangers they faced.

The CPJ data reveal that 75% of the journalists murdered worldwide between 1992 and 2019 were reporters covering politics, corruption, and crime; that many of them were highly vulnerable local reporters; that print reporters headed the list of the murdered journalists followed by broadcast reporters, editors, columnists and commentators, publishers and owners, internet reporters, photographers, producers, camera operators, and technicians. The CPJ also found that in a large number of cases the journalists received threats before they were killed, that nearly a third of the murdered journalists were first taken captive, and that the majority of those taken captive were tortured to send out a ‘chilling message’ to their colleagues. As for the perpetrators, political groups, including Islamic State and other extremist organizations, were suspected to be behind the murders in about one-third of the cases, and government, military, and para-military officials were ‘the leading suspects’ in more than a quarter of the cases.

What is as shocking as the rising number of journalist fatalities and the proliferating violence against them is the fact that the killers and assailants regularly go unpunished. This impunity is a phenomenon witnessed not just in India but also in several other developing countries where authoritarian rulers, typically elected and functioning under the cloak of ‘democracy’, and extremist political movements have little time and tolerance for independent journalism. Investigative reporters especially are targeted as enemies of the state, or the party, or individual political leaders, or of the extremist movement.

Since 2008, CPJ has been publishing an annual Global Impunity Index, a quantified ranking of countries where journalists are murdered, the cases remain unsolved, and the killers go free. In other words, the Index is a graded indictment of countries where the rule of law does not seem to apply when journalists are murdered in the course of their work. CPJ notes that “in the past decade, at least 324 journalists have been silenced through murder worldwide and in 85% of these cases no perpetrators have been convicted. It is an emboldening message to those who seek to censor and control the media through violence.” The 2018 Index identifies 14 countries in which “impunity is entrenched.” The 14 countries appearing in the 2018 Index account for 82% of the unsolved murders of journalists worldwide for the decade. India, along with six other countries, has figured in the Global Impunity Index every year over the decade. It can thus be described as a founding member, a permanent member, of this Club of Shame.

I think I have said enough to give you an idea of the extent to which freedom of speech and expression and freedom of the press has been eroded and the constitutional guarantee as well as the rule of law has been compromised in India.

Let me now conclude with a reminder that a lot of work awaits us in effectively meeting these three big challenges confronting India towards the end the second decade of the 21st century – the challenge of mass deprivations, the challenge to secular, democratic, and pluralist India, and the challenge to free speech and freedom of the news media. Dr. Dabholkar’s life and work demonstrated, among other things, how these challenges are inter-connected and how without meeting them scientifically, effectively, and fearlessly, our country cannot do well. Working hard at the grassroots and in the socio-political arena to raise popular awareness and mobilize the working people behind the fight for secularism, democracy, socio-economic justice, and the republican Constitution is the key to national advancement.

End.

(Part 1 and part 2 of the lecture can be read here and here respectively.)

Tags: The Hindu Narendra Dabholkar Speech Three Challenges facing contemporary India Memorial Lecture नरेंद्र दाभोलकर द हिंदू एन राम भाषण इंग्लिश Load More Tags

Add Comment