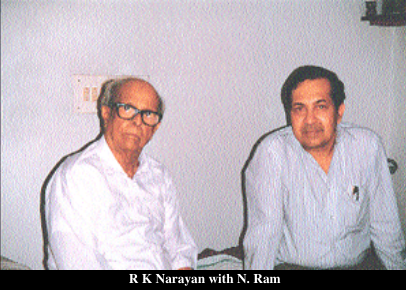

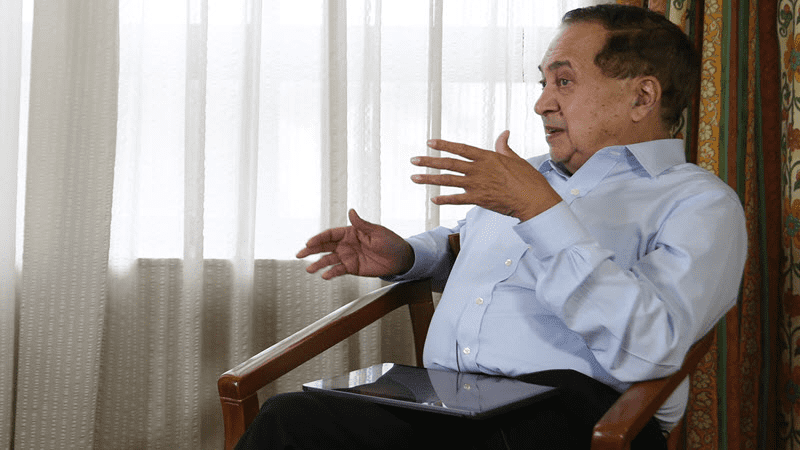

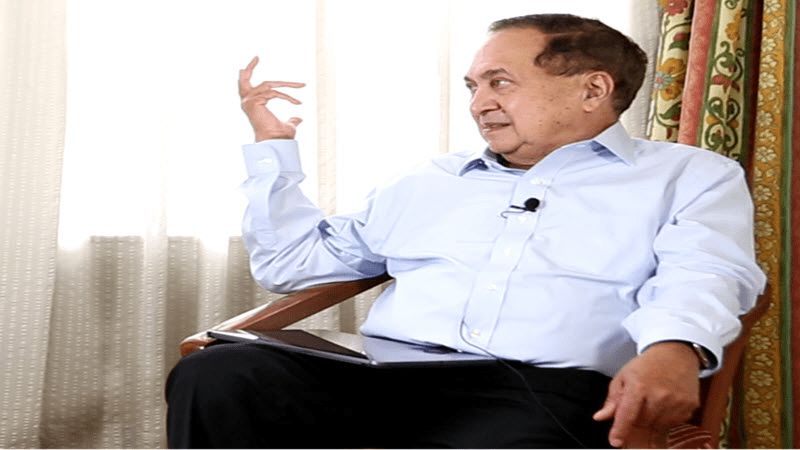

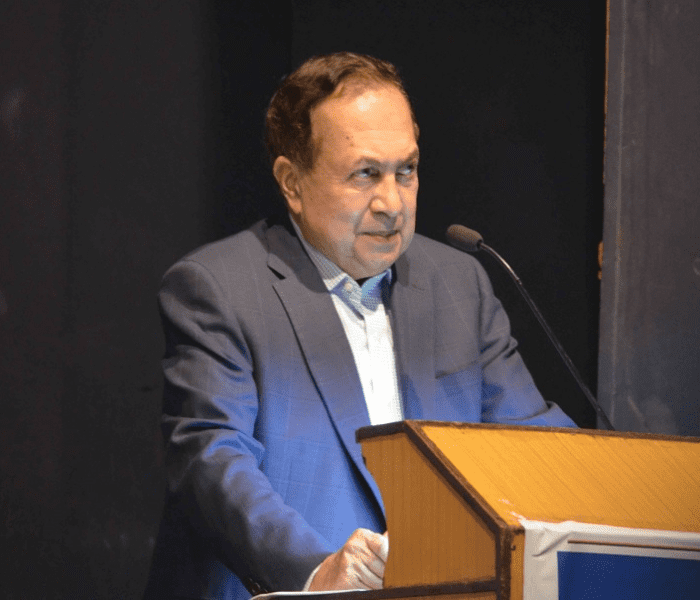

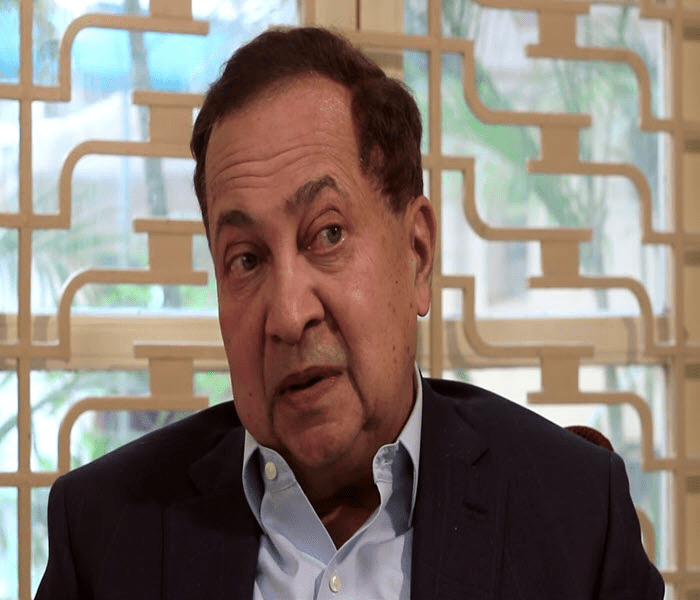

N Ram was Editor-in-Chief of The Hindu during 2003-2012. He was also the Chairman of The Hindu Publishing Group. Mr. Ram was in Pune for delivering the first Dr. Narendra Dabholkar Memorial Lecture on 20th August 2019 and spoke to Sankalp Gurjar at length about The Hindu’s past and present. In this free-wheeling conversation, he sheds light on The Hindu’s editorial philosophy, the role of the newspapers, the potential of print, emerging digital strategies, and a host of other issues such as investigative journalism and the Wikileaks. The interview explains how and why The Hindu remains the best Indian newspaper and offers valuable insights to journalists. This is the first part of a three-part interview where N. Ram talks about the growth, success, and credibility of The Hindu

The Hindu is considered the best Indian newspaper. What’s the reason behind this? Could you offer us an insiders’ perspective?

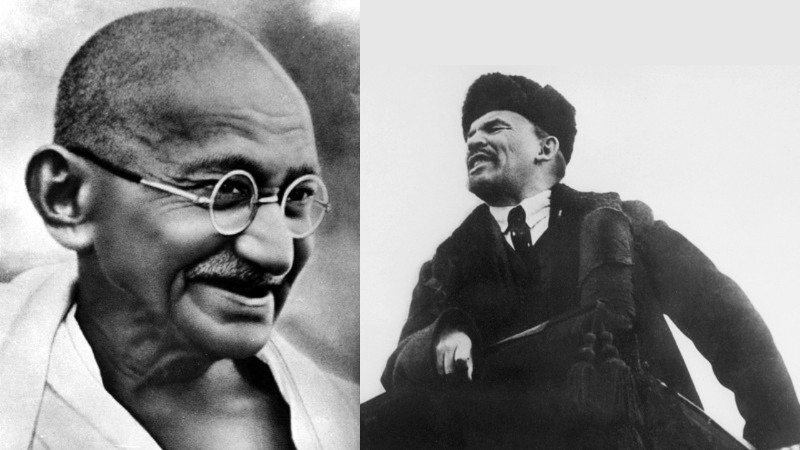

I think we are one of the best, and perhaps the most respected newspaper in India. We have been around for 141 years. The Hindu played a role in the freedom struggle. It had a close association with Gandhiji and Jawaharlal Nehru and others. We have enjoyed credibility and continuity since then. We are probably the oldest surviving newspaper in the freedom movement tradition. (There are newspapers in India older than us that had supported the British Raj; today, of course, they are in Indian hands.)

We have always tried to maintain the best standards in journalism. The Hindu has respected the line between the editorial and business sides of the newspaper without compromising too much. There have been some aberrations over the years but, by and large, we have stayed the course. In today’s journalism, there is a lot of editorializing in the guise of news, which I think is an occupational disease. On TV you see it happening flagrantly. That’s one reason why you see a lot of incompetent stuff on TV. A reporter who knows very little about the subject is asked by his bosses, by anchors, to offer his or her opinion. Of course, in daily newspapers, it will happen when you report on sports like cricket, because in the age of live TV coverage, you can’t just report ball by ball. You need to comment. There are other areas such as culture and literature where you need to express your opinion. But for a daily newspaper – I have long believed this – one recipe for success is to keep news reporting relatively isolated from comment. It is impossible to do it completely, but you have to try to do it. I always used to tell our reporters: don’t opinionate in the guise of news.

In the long run, if you maintain your independence and integrity, you will do well. You have got to look after your people well. Train them, give them opportunities to travel. Don’t put too much pressure to deliver immediately. Accept failure. If you go for an investigation, you don’t always find what you’re looking for. You have got to spend time and money on that. These are some of the things that have stood The Hindu in good stead. When I was the editor, we drew up our own ‘Code of Editorial Values’, which can be read on our website. It was implied before it was put in place as a Code. You can see the consistency if you go back to the founding editorial title ‘Ourselves’ and compare it with the Code of Editorial Values. It was very clear what the newspaper’s mission was. Although the world has changed, the newspaper industry has changed, and even The Hindu has changed, it still retains that commitment towards good journalism, professional journalism of high quality.

Another reason for our success has been the adoption of technology. The Hindu has always adopted modern technology. We were based in the South. Therefore, at one point we printed copies in Madras and deployed our aircraft to cover almost the whole of southern India. Then we started using facsimile to transmit whole pages for printing in various edition centers. That’s how we expanded our reach. When satellite technology became available, we started printing in Delhi as well. The Hindu benefited a lot from the arrival of new technology and from our readiness to adopt this technology. Today, it’s a different world. Everybody has access to technology, the question is, can you afford to use it? We also used technology to make The Hindu more attractive in terms of color, photographs, graphics, and design. Today the business model for traditional media is under great stress. It has not collapsed yet, but signs of acute stress are visible.

The Hindu was the first major Indian newspaper to launch a website; this happened in 1995. Recently, I read that The Hindu group is focusing on digital strategy. However, The Hindu in print has also been expanding in terms of pages, supplements, and editions. How does the group manage the new, digital technology and also the print?

I think we didn’t underestimate the potential for further growth in print. Audit Bureau of Circulation and Indian Readership Survey data reveal that we have made significant gains in circulation and readership. ACB numbers reveal that The Hindu is the second most circulated English newspaper in the country. Nationally, we are well behind the circulation and readership of The Times of India and far behind the circulation of Hindi newspapers, which is understandable. But when it comes to the circulation and readership of English language newspapers, we are pretty well placed. We publish The Hindu at 21 printing centers and have more than 40 editions. We believe in local coverage. Earlier, The Hindu perhaps didn’t do enough local coverage. But you have to balance local coverage with issues of scale and cost. Just printing is not enough. You need to get sufficient advertising to sustain local editions.

As for digital, very few media players in India have put their content behind a paywall. However, for a long time, no major English language newspaper in India dared to put its content behind a paywall or even a registration wall. Fairly recently, we became the first major English language daily to place our website behind a paywall. Journalism cannot survive if nobody is willing to pay for it. The Guardian in the United Kingdom has recently done something interesting: it invited readers to make voluntary contributions for supporting its quality journalism. That has got the newspapers good revenues. It has also helped the paper to make a turnaround, business-wise, in the UK. I think, digitally, we have done all right. The Hindu’s digital products reach more than 34 million unique users per month. The Hindu’s website is accessed by about 1.5 million unique users, who consume about 2.4 million page views, per day. The Hindu apps are used by about 0.3 million users daily and they consume about 3.5 million page views every day. These numbers are modest when compared with the big media players globally. But you’ve got to do it and raise your game through innovative digital strategies.

Now, we have a digital team that is trying to increase our digital footprint. But the problem is, these numbers don’t give you revenues that can stand any comparison with the print revenues on which we have thrived for several decades. For a long time, The Hindu didn’t have enough journalists on its digital team. The ‘Internet desk’ has its own, unique set of challenges. For example, journalists in India have not been used to filing stories throughout the day. But if you are to succeed on digital platforms, you have to do that. Often, there is too much pressure to produce copy and therefore you don’t get enough time to think and write. You can’t have a website or apps that only offer news, analysis, and comment only in the evening. You have to bring out news round the clock for your website. You have to figure out a way to do it 24x7 without compromising quality too much.

We believe that print is still our backbone, but simultaneously we can’t ignore the opportunities and challenges of digital journalism. Unfortunately, no business model for digital has yet been figured out, although there have been interesting experiments in this area in various countries. The fear used to be that if you put your website behind a paywall, the traffic would come down significantly. When I was an editor, we experimented. We started offering our e-paper, that is, our ‘as-printed’ digital edition, free on the website. I recall that when our e-paper could be accessed freely after registration, we had about 180,000 people registered from all parts of the country, including the Northeast. Seeing that, our business people got a bit concerned about the cannibalization of the print product. So, we decided to put the e-paper behind a solid paywall, and at that time subscription rates were quite high. As a result, numbers came down to a few hundred. Now, we have recovered and the e-paper has about 100,000 paying subscribers. But still, that’s not going to give you the required revenues.

There are newspapers like The New York Times, The Washington Post, and The Financial Times which are doing very well through their innovative digital products and their digital revenues. But they are the exceptions. But let us not underestimate print. On the other hand, Facebook has more than 300 million users in India. WhatsApp also has similar numbers. Instagram is growing rapidly. All these platforms are taking people away from reading printed newspapers. We used to ask our young reporters: how many of them read The Hindu? Very few hands would go up. Most of these young reporters go to the newspaper when they need to check something. At the Asian College of Journalism, with which I’m closely associated, I always ask this question: how many of you read the printed newspaper? And five to ten hands would go up in a class of 175 or 200. You may have a different experience in some Indian languages. Newspapers can’t be in denial. I believe our industry has been in denial for too long about the digital age and its implications for the Indian news media, above all newspapers. Owing to growing literacy levels, we still have space to grow print in India. But the costs are too heavy. Advertising revenues have shrunk. It can no longer be business as usual. This is the challenge we face.

As newspapers are cutting down their costs, they are reducing the number of pages. However, The Hindu has been an exception to that trend. It has done the opposite. How does it manage to do so? Doesn’t The Hindu face the pressure of cutting costs by reducing pages?

We used to be the exception but no longer are. We too have been reducing the number of pages, in the main newspaper as well as in the supplements. Quite understandably, when advertising is shrinking, there’s pressure to reduce the number of pages, especially from the business side. The key lies in stabilizing advertisements, your ad revenues. There is a certain ratio of news and advertisement in a newspaper. If you retain the same level of pagination regardless of advertising levels, you incur losses. If you cut down pages too much, the quality of content goes down. If you are a serious newspaper, you must maintain an optimal balance between the number of pages you print and the revenues (advertising plus circulation revenues) you can net.

The Hindu is the most expensive newspaper in India. How do the readers of The Hindu respond to it?

Newspapers in India are seriously underpriced. People are used to underpriced newspapers. Earlier we used to believe that we were operating in a highly price-sensitive market. But sometimes, you are unnecessarily cautious. When we print in Delhi, Mumbai or Kolkata, you don’t have to sell it at Rs 2 or something like that. It is expensive to print newspapers in these cities. Therefore, your pricing should be such that at least you should be able to recover your costs. You are not expecting to compete with The Times of India in a market like Mumbai. Competition drives the price of newspapers down. Everyone knows that.

We no longer believe that it’s a highly price-sensitive market. People do complain about the increased cover prices but when you explain the realities, many are also willing to pay for it. In the Northeast, they pay Rs. 20 for The Hindu. Our Sunday edition in Delhi is priced at Rs. 15 and the circulation is pretty good. Realistic cover pricing means less dependence on advertisers; this is a global trend, although India is still hugely dependent on ad revenues. Also, when you enter a new market, you know that you are not going to get a lot of advertising revenue because you will be competing with dominant local players. Generally, we can say that ad revenues for print are declining. For television, ad revenues in the entertainment sector are good however, the picture is not encouraging for news channels. But on digital platforms, who gets the money? It’s large companies like Google, Facebook, and a handful of other so-called technology companies. Globally, newspapers’ share of digital advertising revenues is in single digits. Realistic cover pricing for printed newspapers and placing newspapers behind a reasonable paywall on digital platforms is the way to go. People must buy your newspaper for its content and quality, not because it’s cheap. After all, typically in India, a cup of coffee costs more than a copy of a daily newspaper!

To buy a newspaper for its content, a newspaper needs credibility. The Hindu enjoys that credibility. The question is how did The Hindu build credibility?

I agree that trust is the key to a newspaper’s success, certainly in the long run. Naturally, there are ups and downs in the history of a great newspaper. In the early years, there was a brilliant editor, G Subrahmania Iyer (1878-1898). He was a well-known social reformer and economic nationalist; he was one of the founding members of the Indian National Congress in 1885. He fell out with his partner. The first issue of The Hindu came out on September 20, 1878. In the 1890s, it was becoming quite famous. Editorially, it was doing well but economically it was sinking and the partners fell out. Only around 1905, under the new management, did the newspaper begin to look up again. It could have easily collapsed and died in the early years of the 20th century. Since then, growth has been sustained and quite solid. It was taken over by my great-grandfather, S Kasturi Ranga Iyengar, who was a supporter of BG Tilak. He also took bold positions on social questions.

The Hindu was a significant voice in the struggle for India’s independence. However, there are chapters of The Hindu’s history that we cannot be proud of. For example, The Hindu’s record during the Emergency is not something to be proud of. It didn’t stand up. I was not working in The Hindu then: in my way, I was doing my bit against the Emergency regime. The Hindu fell in line with the Emergency; that’s the truth. It was a setback to the credibility of the newspaper. Most of the newspaper industry did that. There were very few who resisted. As Mr. Advani said, quoting somebody, when you were asked to bend, you chose to crawl.

Over the years, we have had very good bureau chiefs and political correspondents in Delhi, like K. Rangaswamy, G K Reddy, K. K. Katyal, Harish Khare, Siddharth Varadarajan, and others. We have also had outstanding foreign correspondents. In sports, we had Jack Fingleton, the Test cricket and wonderful cricket writer, Bradman’s contemporary, who used to write for The Hindu from Australia. He was part of the Bodyline series of 1932-33 (played between Australia and England). I have collected his contributions to our newspaper over the decades; they aggregate a few thousand reports and articles. We had various other distinguished contributors to politics, economics, science, culture, etc. Even Gandhiji wrote for The Hindu from South Africa. I have an issue where his name is spelled as ‘Ghandi’. He wrote about South African Indians. We had dozens of outstanding people writing from outside for The Hindu.

Over the years, we have had very good bureau chiefs and political correspondents in Delhi, like K. Rangaswamy, G K Reddy, K. K. Katyal, Harish Khare, Siddharth Varadarajan, and others. We have also had outstanding foreign correspondents. In sports, we had Jack Fingleton, the Test cricket and wonderful cricket writer, Bradman’s contemporary, who used to write for The Hindu from Australia. He was part of the Bodyline series of 1932-33 (played between Australia and England). I have collected his contributions to our newspaper over the decades; they aggregate a few thousand reports and articles. We had various other distinguished contributors to politics, economics, science, culture, etc. Even Gandhiji wrote for The Hindu from South Africa. I have an issue where his name is spelled as ‘Ghandi’. He wrote about South African Indians. We had dozens of outstanding people writing from outside for The Hindu.

These days, news can be procured from global news agencies and yet The Hindu has foreign correspondents. Foreign correspondents are expensive. What value do they add to the newspaper?

Yes, we do have foreign correspondents. It is very expensive to maintain foreign correspondents. We believe in them because they are expected to follow developments in those countries and present it attractively to Indian readers. They don’t just cover bilateral issues. They cover political, economic, and cultural developments in the countries and regions where they are stationed; news agencies can’t do that for you. Even PTI doesn’t do it. Over the years, we have had some outstanding foreign correspondents. K V Narayan used to write from Japan. After the Second World War, he was on his way to the US but stayed in Japan and became a legendary figure there as our permanent Tokyo Correspondent. No other Indian newspaper had anyone like him. Our U.S. Correspondent, K Balaraman, based in New York and subsequently in Washington D.C., was another distinguished foreign correspondent. My brother, N. Ravi, and then I, were also Washington correspondents for a couple of years. We had a brilliant writer and journalist, K.S. Shelvankar, writing for us from London over a long period. Apart from foreign correspondents, The Hindu also published literary contributions from outstanding writers. Let me give you a few examples. From about 1935 until the late 1990s, the great writer R K Narayan contributed short stories and personal essays to The Hindu or other group publications.

My favorite cartoonist, The Times of India’s R K Laxman, used to do drawings for us, to illustrate his elder brother’s short stories and serialized novels. Amartya Sen, Noam Chomsky, Girish Karnad, Arundhati Roy, Subramanya Bharathi...I won’t go on. Any newspaper that’s been around for a century and more can boast of such writers, contributors from outside as well as staff journalists. We have had a very large number.

My favorite cartoonist, The Times of India’s R K Laxman, used to do drawings for us, to illustrate his elder brother’s short stories and serialized novels. Amartya Sen, Noam Chomsky, Girish Karnad, Arundhati Roy, Subramanya Bharathi...I won’t go on. Any newspaper that’s been around for a century and more can boast of such writers, contributors from outside as well as staff journalists. We have had a very large number.

Is that why The Hindu is taken seriously across India?

I think, yes, it’s one of the reasons.

The Hindu is unique in the sense that it’s the only influential newspaper that is not based in the national capital. The Hindu is based in Chennai.

I think that is an advantage for us. Being away from Delhi, The Hindu can take a relatively cool view of what is happening there. The British journalist Neville Maxville described The Hindu as ‘a national voice with a southern accent’. I think it is a correct depiction of how we see ourselves at The Hindu. Close association with the freedom struggle and the right distance from Delhi can be considered two of our advantages; actually, the first is an asset, the second a historical advantage. Now, of course, the freedom struggle seems to have zoomed out into the distance but for much of the 20th century, the connection was live and important. We have been publishing excerpts from 100 years ago and 50 years ago on our Op-ed pages. Very few newspapers can do that. But the main reason for our success and credibility is that we have survived for such a long time and continued to be relevant to millions of people. Sadly, Amrit Bazar Patrika, one of the country’s oldest newspapers in the freedom movement tradition, couldn’t survive.

Part 2 of this three-part interview can be read here. Part 3 can be read here.

(Kartavya is celebrating its first anniversary on 9th August. On the backdrop of this special occasion, we will publish comprehensive interviews of three renowned editors of English journalism for seven consecutive days starting today, that is, August 9th to August 15th.

N. Ram's interview will be published in three parts and will shed light on the past and present of The Hindu. Naresh Fernandes' interview will be published in two parts and will talk about Scroll.in. And lastly, Shekhar Gupta's interview will be published in three parts which will address his career with The Indian Express, India Today, and The Print. Although these editors belong to three different generations and have a differing point of view on some issues, their commitment to the core values of journalism is alike.

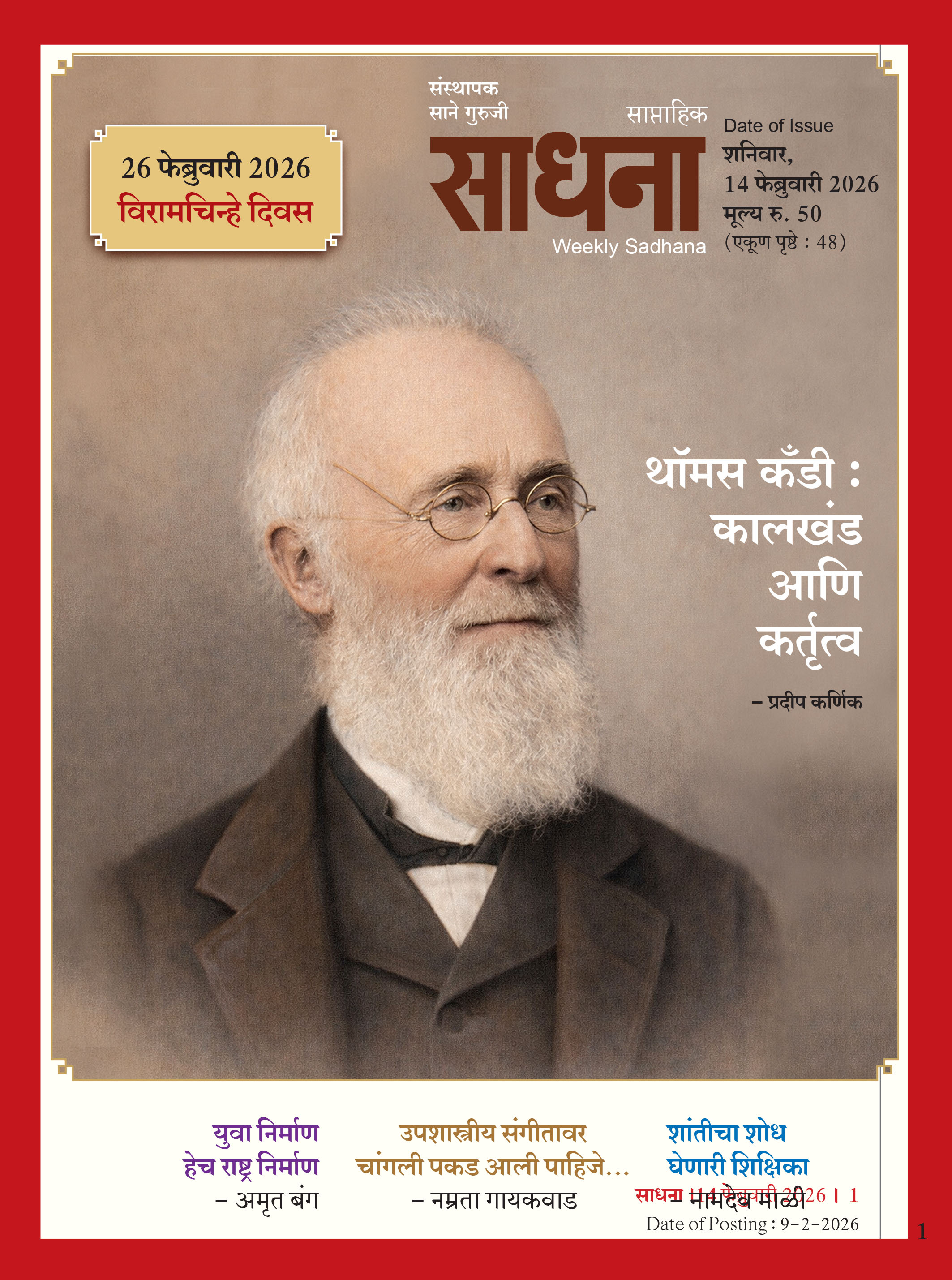

The Marathi translation of this interview has been published in the 15th August 2020 edition of weekly Sadhana.)

Tags: the hindu interview N Ram sankalp gurjar journalism jawaharlal nehru mahatma gandhi dr. dabholkar Load More Tags

Add Comment