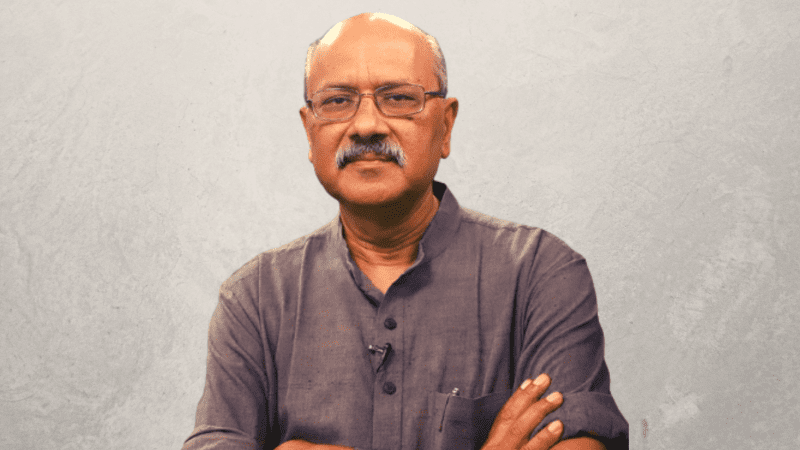

Shekhar Gupta is currently the Chairman and Editor-in-chief of The Print. After starting his career as a reporter with The Indian Express, he went on to work as a reporter and then an editor at India Today. He has also been the editor-in-chief of The Indian Express from 1995 to 2014. In this unreserved conversation with Jayali Wavhal, he talks about the evolving idea of journalism and India - based on his experience, the dynamics of print and digital media, the journalistic ideals and principles that he has always braced, while also offering valuable insights to journalists.

I never signed my contract with India Today. I did go there; the intention was to join. The arrangement was that I will join, but I will also develop a product of my own - like The Print. I figured that if I got fully involved with India Today, there will be no time left for my product. I thought that at this point, did I find a regular wage-paying job more exciting and interesting - India Today is a large organization - or would I be better off taking a risk and focusing on doing something of my own? So, the idea of building a new newsroom, I think, was more fascinating. That's the choice I made. Within weeks, we had a conversation. Arun Purie and I - we decided that I wasn't going to continue. I think it's the best decision that we took.

The Print started in August 2017. It has a tagline - ‘Substance of Print, Reach of Digital’. Could you tell us more about it?

I will tell you where the name The Print also came from. This name was tossed earlier in a conversation with someone in a brainstorming session. Sharad Pawar’s 75th birthday celebration took place in Delhi. We were all invited and I had another eminent former editor sitting next to me, who shall not be named. I shall not name him because why blame him for it. I said to him – who is someone senior to me and much older to me - that look, I was just coming in and I read this article on one of the digital platforms by its editor, saying that with this 75th birthday celebration where Modi, Sonia Gandhi, Pranab Mukherjee - everybody was coming, Sharad Pawar had now emerged as the main candidate to be the next President of India. I said this is the 75th birthday. This is Indian politics. Everybody is a hypocrite. Everybody will end up if invited for a 75th birthday party. It doesn't mean that they will make Sharad Pawar the next President. And if Narendra Modi has such a full majority, and BJP can get their president elected, why would they give the position to Sharad Pawar? What kind of analysis do you get from such a senior experienced byline who should know better?

This person said that look, that's what happens when you go from print to digital. You lower your guard and you lower the bar. You think digital mein sab kuchh chalta hai. Print is different. So, then we thought that let Print be the name because that's the way of saying that while a platform is digital, we apply the diligence of print media. So, there was a little twist to it. Reach of digital - of course, reach of digital is more than print, and at the same time, as I said, it has the substance of print. We are not in a rush to catch the first algorithm. We don't rush with the stories unless we check it first.

The Print became one of the most successful portals within a short period. While it did have the advantage of your legacy, what else added to the success?

I think several things happened. One, I think, that a great deal came along. Some experienced people, some of those who had worked together, and some who didn't know much. New leadership came in too. And then we attracted a lot of bright, and very young crowd. There is nothing more satisfying than building a new newsroom for an editor. Another thing that happened was Indian politics and journalism - both got very polarized. So, there's this line that I wish I had invented, but someone else did – “half the news organizations seem to have become chamcha, and the other half morcha.” In that situation, the idea of the space opened up for an organization, which was non-hyphenated. Although I must say that on any given day, somebody will accuse you of being hyphenated. But if you get attacked by both left and right, you must be doing something right.

First thing was speed. For a traditional journalist, the most unsettling thing is knowing immediately how many people are reading you. When you are in a newspaper, your neighbors, your family, your landlord, your 25 sources, and friends will all say, “Maine padh liya!” So, you think it's been a big hit. But in digital, you know immediately ki aap kitne paani mein ho. That is a big eyeopener in digital.

The other thing is, in digital, you realize that – one, you have the benefit of enormous space, endless space, limitless space; but you also realize that the reader has limited time. So, how do you find the balance between the quality length of an article and the reader's mind space? I think those are the things that you learn in digital. You also learn minor craft like keywords and all that, because ultimately digital is at the mercy of artificial intelligence.

There is competition, but I would say that we have grown phenomenally in this period. So, we must be doing something right. The other thing is that this will settle at some point. But legacy media will then realize that while they may get a lot of traffic on the internet, their cost base, because of the newspaper and TV channels, is very high. So, we can build the same mind space and the same audiences at a much lesser cost. We don't need a printing plant or a studio. We don't need to give money for distribution to cable channels. I think the economics of news media will now get completely redefined. Let's see. I think it will be a bigger challenge. It is a big challenge for us because we are so new and we have no reserves. We hardly have any revenues. There are only beginning to come in now, slowly. But legacy organizations also have much larger cost bases, so they will have to look at that very carefully.

Ultimately, I think everybody will go behind paywalls. At least for some of the products. We are not yet behind a paywall, but we are appealing to our readers saying that, look, we are not going behind a paywall. We are offering this to you for free. But if you appreciate good journalism, you should voluntarily pay for it - not as a donation, as a subscription. So you don't have to, but if you appreciate good journalism and you know that without you paying for it, it cannot be sustained, then pay for it. We are encouraged by the fact that a lot of people are helping us. I wish more would, and we will keep trying. But at some point, we will put something behind the paywall, if not everything. For now, we are not doing that.

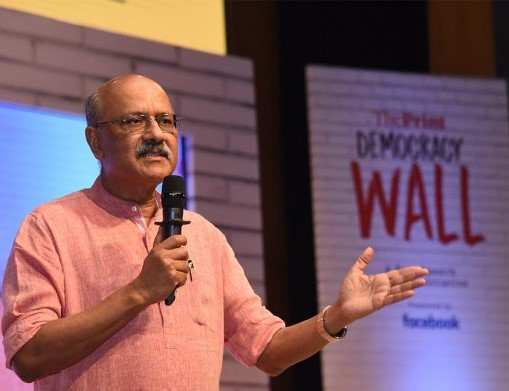

The Print started with the Democracy Wall to provide a platform for young people to express themselves. How was the reception of this initiative and what have been your observations about it?

Well, it worked very well. Democracy Wall was in partnership with Facebook, and we have had two seasons of it over 2 years. Now the third season, we will figure out. It's an on-ground event. You can't do anything on the ground because of COVID-19. We will figure it out. But we are starting something new called Campus Voice or CV, where we will now be opening up the opinion field and asking bonafide students to write their opinions on key issues of the day. We will then choose the three best articles every week and give them very good prizes and publish those on our platform. Otherwise in India, the opinion industry is controlled by 20-30 bylines, including mine. So, we are just trying to widen this reach now.

Well, it worked very well. Democracy Wall was in partnership with Facebook, and we have had two seasons of it over 2 years. Now the third season, we will figure out. It's an on-ground event. You can't do anything on the ground because of COVID-19. We will figure it out. But we are starting something new called Campus Voice or CV, where we will now be opening up the opinion field and asking bonafide students to write their opinions on key issues of the day. We will then choose the three best articles every week and give them very good prizes and publish those on our platform. Otherwise in India, the opinion industry is controlled by 20-30 bylines, including mine. So, we are just trying to widen this reach now.

Will these be three best opinions across the nation?

That's right! So, any bonafide student can contribute to this.

The idea behind this was that I found a lot of journalists were tweeting. And they were saying stuff on Twitter which was being read a lot. Most of them were not doing faltu tweeting. They were making good points. So, I thought you can make a good point in a tweet. Now, what is an editorial? An editorial is not an analytical article. It is a point of view. So why can't you say your editorial view in a tweet? So, I just calculated. 280 characters are what a tweet allows. 280 characters are about 50 words. That’s how the idea of a 50- word edit came in. So, if you can't make your editorial point - you agree with something, you don't agree with something, why - then you are wasting somebody's time. Why should people read 400-600 words edits if you can make the same point in 50 words? It's a challenge, but I think it's quite popular and it's working well.

The Print also launched a feature section titled ‘Brandma’ in October 2018? Could you tell our readers about it, and the motivation behind launching it?

I think in a way it betrays my vintage. See, all the brands that you remember, you will not know the biscuit brand called J. B. Mangharam. But if somebody says J. B. Mangharam to me, I can get the flavor of the biscuit in my nostrils. So, there are lots of brands which were part of our lives growing up, and a lot of people have grown up. Not everybody is a teenager. So Brandma was partly nostalgia, partly India's social history - because brands tell you your social history. The history of Colas in India tells you India's economic history. It's the only country in the world, I think, where the government produced Coca Cola. Janata Party government-produced Cola, after George Fernandes threw Coca-Cola out. That government-produced Cola called ‘Double Seven’ because that government came into power in 1977. So, these brands tell us a lot of things. These are also things that you can now research, you can find old commercials of. It is very interesting. Also, many of these brands are about products that are not relevant anymore or which are not used anymore. Who uses a Murphy radio anymore? But everybody watches that film called ‘Barfi’ because the kid was called Murphy. So, how many people today relate themselves to the Murphy baby? This is an interesting thing and I think we talked about the idea. I think somebody said ‘Brandpa’, and we have a newsroom full of women. So, they said, “No! Brandma, not Brandpa. It's a mother brand, not papa brand.

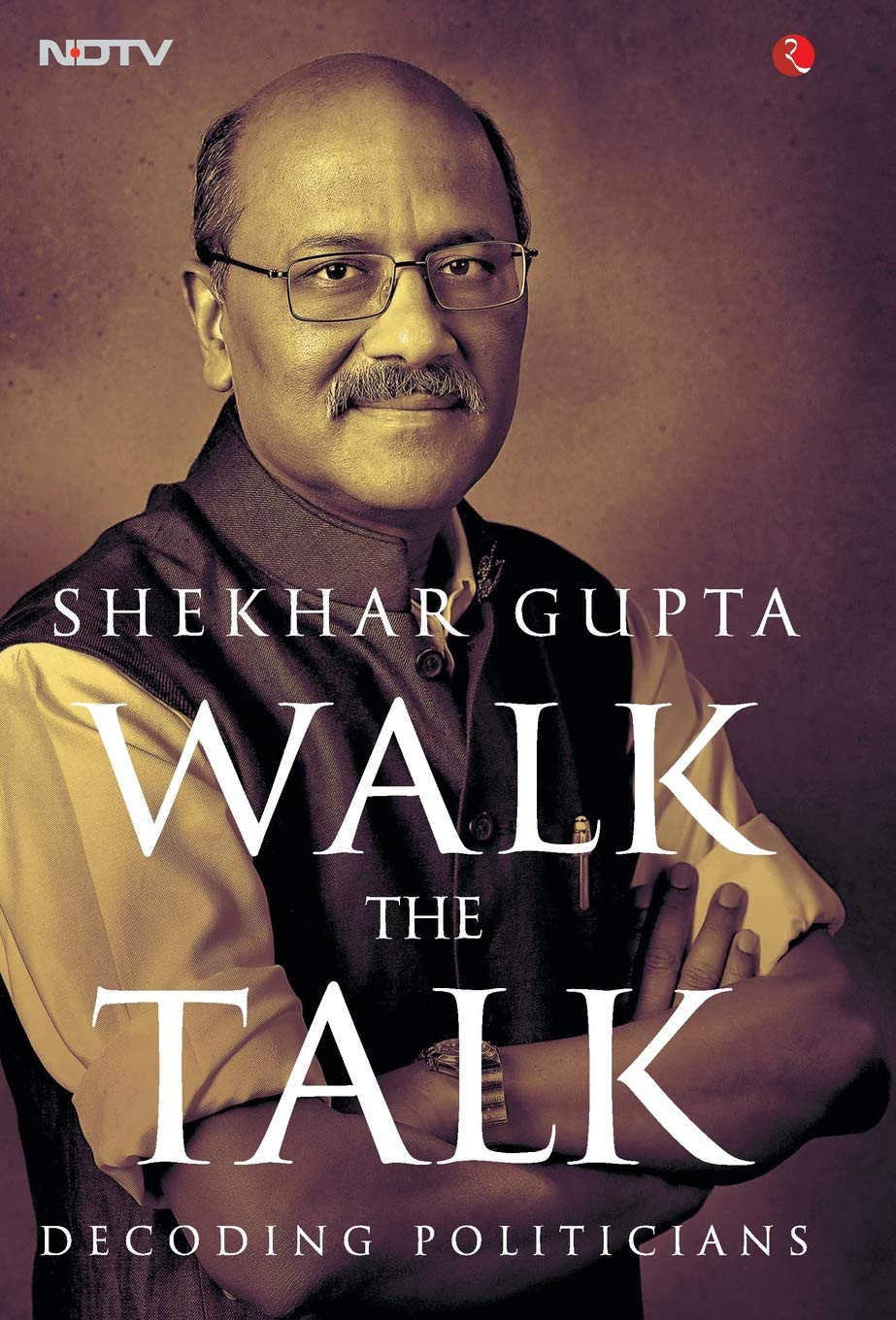

When talking about your career, we can’t leave out your talk shows, ‘Walk the Talk’, ‘Cut the Clutter’, and ‘Off the Cuff’. You have built a very high-quality audience with these shows, and you have also made the show relatable to many with the diversity of your guests. How did you manage to pull make this show so inclusive?

Well, I think, if you ask me, I would love to say that I planned it. I am a genius. But no such thing happened. One thing led to another and ultimately, what helps you is your innate obsessed curiosity. Curiosity if you are happy to meet new kinds of people. I think that's the best thing about a journalist’s life because you end up with an opportunity to meet a lot of people who are much brighter than you, much more talented than you, in many different fields. And when we do that, you read up on them, you understand about them, and you learn from them. So, I think it's just curiosity that keeps taking us from one thing to the other.

Well, I think, if you ask me, I would love to say that I planned it. I am a genius. But no such thing happened. One thing led to another and ultimately, what helps you is your innate obsessed curiosity. Curiosity if you are happy to meet new kinds of people. I think that's the best thing about a journalist’s life because you end up with an opportunity to meet a lot of people who are much brighter than you, much more talented than you, in many different fields. And when we do that, you read up on them, you understand about them, and you learn from them. So, I think it's just curiosity that keeps taking us from one thing to the other.

Cut the Clutter has been stirring dynamic conversations, among young people, especially students. What was the idea behind it?

Cut the Clutter again, is a concept that came in chalte-chalte, because once again we realized that people were getting very bored with TVs. It was all so-called debates where you-know-who is on which side. It’s gali-galoch debate where you get no understanding of news. Also, the institution of the daily news bulletin has now disappeared from anywhere. So, the idea was to choose one or two of the major stories of the day. People may be watching a lot of debate and discussion, but may not be understanding the basics. So, Cut the Clutter is usually done by taking off the layers of a complex story without taking a position. Occasionally, when I do take a position, I often say that I will also be giving you my opinion, but it is essentially looking at facts of a story. I will also be speaking from experience - and experience comes from both ways - experience comes from finding examples that one may be familiar with, but also from being able to know where to find the information. And we have a very good and young team who at any point in time will help me with the information.

I work in chaos. I cannot work in a structured way. So, at one level it's negative. That's the reason I will make a very bad bureaucrat. My mind is entrepreneurial. You can call it creative. I am always thinking of new mischief. That's how this idea of Campus Voice has come in. Let's see if it works. But I think it will work because nobody has tried it yet. I do think that we have to now challenge the opinion industry in India because the same 20-30 bylines talk about everything. I think we need to ‘democratize’ opinion without trivializing it.

How can a journalist ensure that they do not succumb to their biases while covering a story?

First of all, no one can be completely free of one’s own biases. But that's where professionalism comes in and that's where the role of the editor comes in. So, in any organization, or newsroom, there have to be layers. Even when I write something, somebody edits it very carefully and I defer to the person who edits it. One change that you might find with my writing now, in my National Interest column, is that it's much crisper than before. A lot of people have told me that. And I will tell you why it has changed. Because now there is an editor that I am afraid of.

When I was my editor in the Express, I could write routinely 1700- 1800 words - space will be made, the second article will be dropped, yahan ke hum hain Rajkumar. But not this column because it goes in Business Standard too. The editorial chairman of Business Standard is T.N. Ninan, who was my editor at India Today a long time back, and who I respect enormously. I know ki faltu likhega to Ninan kya bolega. Secondly, I know that they can only publish 1250 words. So, I routinely write 1700-1800 words, then I cut it down to 1200-1250. I am now able to do it in no time, so that discipline is working well for me. That discipline wasn't there when I was my editor, so everybody needs an editor.

How can media channels and journalists protect their freedom to practice journalism freely?

Look, flak will come. If you don't want flak, don't do it. So, it's the old line, I think Truman said it – “if you can't face the heat, get out of the kitchen.” Flak will come, so you have to deal with it. As long as you know that you are not coming from an agenda, that's a good place, to begin with. Secondly, when you make mistakes, say sorry. Don't try to compound the mistake that ‘no, this must be right’, or by trying to duck and say this will pass. If it's a mistake, then say sorry. Audiences quite appreciate the fact that you admitted to your mistake. Of course, you can't do it every day. You can't make a mistake every day. But if you do make a few mistakes as possible, then grab your ears and say, ‘sorry, I shouldn’t have done it’.

My answer to that is a very straightforward one. I am very parochial when it comes to our profession. When you give me citizen doctors and citizen lawyers, I will give you a citizen journalist. Journalism is a profession. You have to be trained for it, you need skills for it, and you have to be held responsible for what you do. Citizen journalism for me is a nothing concept. I don't buy into it frankly. I think it's an abomination.

First of all, they are so much brighter and they are hungry, they are curious. So, these are very good qualities. Secondly, just from personal experience - I was similarly spoilt by my editors when I was that age - I was sent to cover the North-east, which was India's most sensitive beat, by Arun Shourie. I was not even 24 years old. You have to trust people, you have to trust your instincts, that I think if I push this person into water, then they will swim and not drown. But if somebody is drowning, you are always there to be the lifeguard and rescue the person. I find that you do quite well with that over time. You should not hold anybody’s youth against them.

The second thing is a lot of stories are to be done by young people. When the war in Kargil was going on, sometimes senior people in the army would get irritated with some of our stories. And our reporters were very young. One of them - Gaurav Sawant, who is now with India Today, he was 25 years old at the time of war in Kargil. He was covering it and once I got a call from a very angry retired general saying why do I send these 23- 25-year olds to cover the war in Kargil? Why don't our senior people go? So, I said, “Sir, why do you send these 23- 25-year-old captains to take those peaks? Why don't you generals go and take those peaks?”

Some things are to be done by young people; some things are to be done by older people. A lot of these stories are for young people.

What advice do you have for prospective journalists?

I don't know what can I say. I can say safely that when you become a journalist, one thing that will never stop in India is good stories and surprises. Because there is very little that you can anticipate in India. You don't know what will happen tomorrow. That is very good for journalism. The second thing is, stay curious. Everything else can be learned. Somebody can teach you; somebody can rewrite you; somebody can teach you language; somebody can help you get the sources. But you have to be curious. Because if you are not curious, then you can't be a successful journalist. And thirdly, if you grow into a leadership position, have a big heart because nobody can be a good leader without having a big heart.

Part 1 and part 2 of this three-part interview can be found here and here respectively.

(Kartavya is celebrating its first anniversary on 9th August. On the backdrop of this special occasion, we will publish comprehensive interviews of three renowned editors of English journalism for seven consecutive days starting today, that is, August 9th to August 16th.

N. Ram's interview will be published in three parts and will shed light on the past and present of The Hindu. Naresh Fernandes' interview will be published in two parts and will talk about Scroll.in. And lastly, Shekhar Gupta's interview has been published in three parts which will address his career with The Indian Express, India Today, and The Print. Although these editors belong to three different generations and have a differing point of view on some issues, their commitment to the core values of journalism is alike.

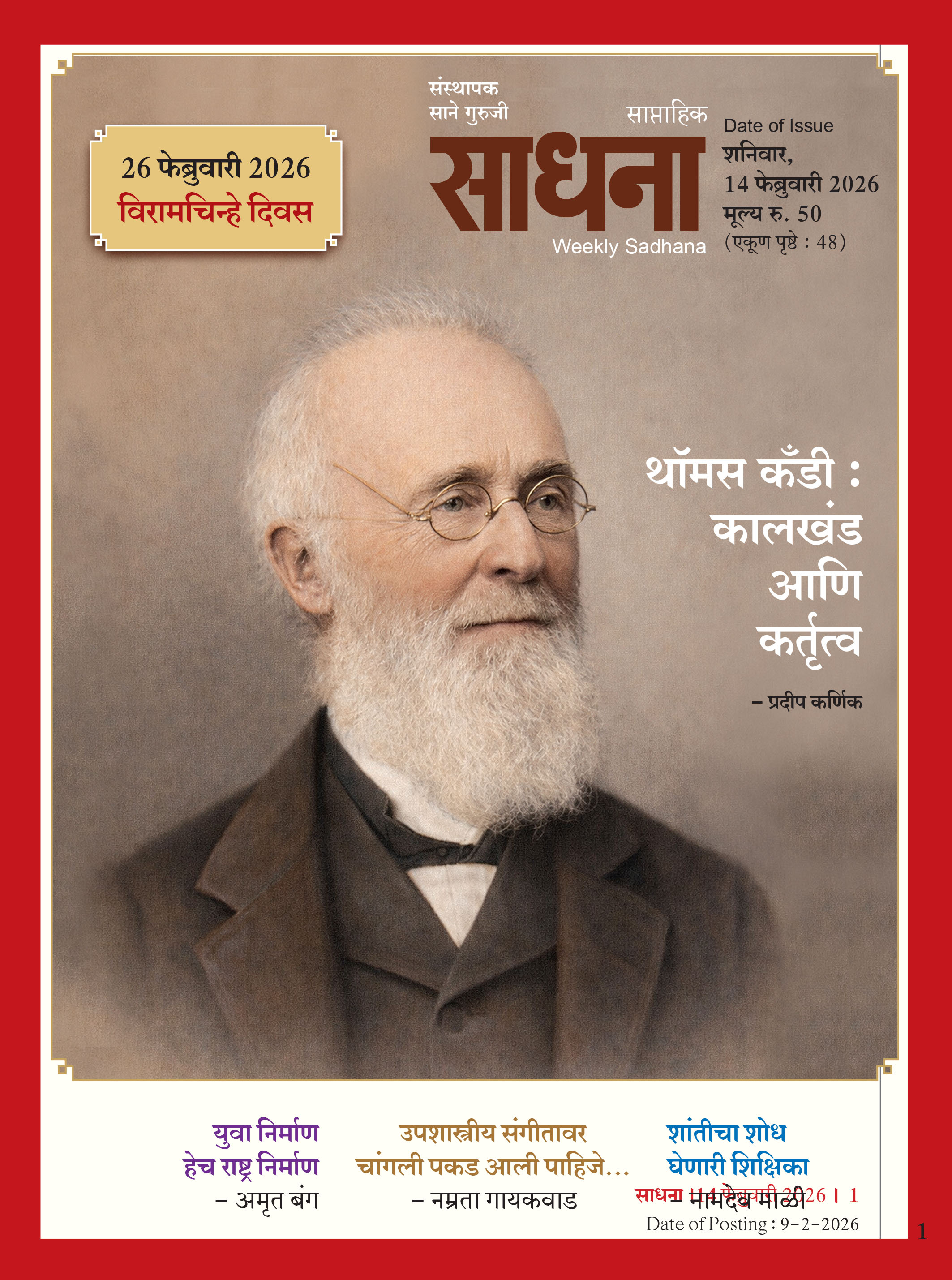

The Marathi translation of this interview has been published in the 15th August 2020 edition of weekly Sadhana.)

Tags: shekhar gupta the print the indian express india today interview jayali wavhal journalism Load More Tags

Add Comment