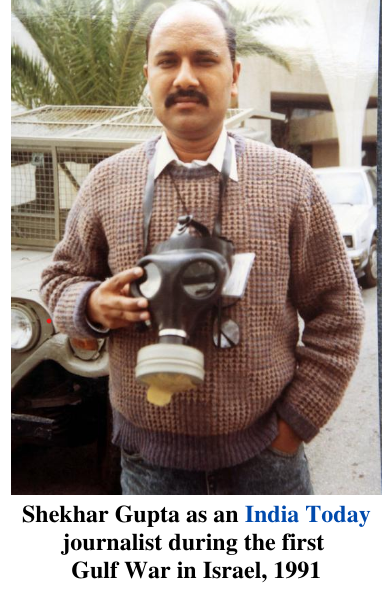

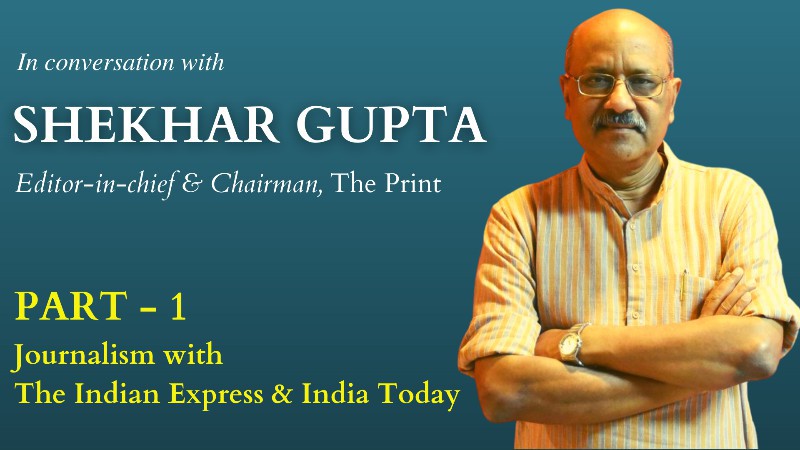

Shekhar Gupta is currently the Chairman and Editor-in-chief of The Print. After starting his career as a reporter with The Indian Express, he went on to work as a reporter and then an editor at India Today. He has also been the editor-in-chief of The Indian Express from 1995 to 2014. In this unreserved conversation with Jayali Wavhal, he talks about the evolving idea of journalism and India - based on his experience, the dynamics of print and digital media, the journalistic ideals and principles that he has always braced, while also offering valuable insights to journalists.

After completing your schooling from Haryana and Punjab, you have said that you were always interested in arts, but you graduated in science. How did you decide to pursue a career in journalism?

I graduated in science. For two years, I got very poor marks, and in the next two years, I got very good marks. But essentially, my heart wasn't there. I didn’t know what to do. It's one of those good coincidences in life that my mark sheet came with a spelling mistake in my name because those days university mark sheets also came written by hand. Instead of sending it by email, as those days there was no courier - I'm talking of 1975 - I went to Chandigarh, to Punjab University, to get my spelling corrected on my mark sheet. While I was there, I saw a noticeboard with a notice for the entrance test for the Journalism department. The next morning was the test, and I appeared for it. It wasn't a very difficult competition because I think there were 50 applicants for 25 seats. And by the same afternoon, the results were declared. So, I thought, "Theek hain, let's do this". It wasn't planned that way, but it happened that way, and it all happened for the better.

What was your initial idea about journalism as a profession?

Well, we were a lower-middle-class family in a small town in North India. So, even in days when we had strained family finances, we always got two newspapers – one in Hindi, one in English. And a couple of magazines- two Hindi magazines and a couple of English magazines. So, there was always a familiarity. And there was a lot of radio. Because television or Doordarshan had still not reached out beyond 50-60 km of Delhi. So, we had very little access to TV. But radio was a big source of knowledge and journalism - particularly BBC and other radio stations overseas. There was a lot of exposure to journalism and a lot of familiarity too. But there was no family tradition as such.

In my college, I used to bring out a weekly publication - like a campus newsletter. But that was set with hands. It was just college news. I think the college had some funds for these cultural activities or whatever. And there were a couple of very good teachers in the English department - although I wasn’t studying in the English department. But because they thought I was the curious type, I suppose, they asked me to bring it out. That was it, but it wasn’t very much. It was called College Praangan which means college campus.

After you completed your graduation, how did your journey begin with The Indian Express in 1977 as a reporter?

I passed out in the summer of 1976. As you know, 1975-77 was the Emergency and there were no jobs. So, if things are bad in journalism today, they were enormously worse in that period. Because firstly, in any case, journalism was not so big, and secondly, because of the emergency, there were no jobs. So, when I was studying journalism, as part of our course, we spent six weeks on an internship with a media organization. I spent six weeks with The Times of India in Delhi. There was no work at The Times of India. I was discouraged by well-meaning people saying, “Why are you wasting your time with journalism? Go back to studying science!” But Usha Rai was there, and she advised me to go to the sports desk since I was interested in sports. And I got to do some work for the sports desk. I was always very interested in sports.

When I was going back to Chandigarh, the sports desk said, you become a stringer - only covering sports outside Chandigarh. So that was Re.1 per column inch, and a retainer of Rs.95 per month. I went back and I enrolled myself in Punjab University again, in the economics department, where I never attended a class. Never sat for the exam either. But that was only to get a hostel room. For the next few months, I carried on like that, and also did a fair bit of freelance writing for The Times of India when Darryl D’monte used to run it.

There was a publication called Youth Times which later shut down. And many other publications. That’s how several months were spent. I think by December 1976, I got my first job in a tiny magazine in Delhi called Democratic World, which was a one-and-a-half-man office. The editor was one man, and I was the half-man. And while I was there, I had the sports editor of The Indian Express, Mr. K. R. Wadhwani, tell me that whenever their edition starts in Chandigarh, he will make sure that I am recruited. And that’s what happened.

The emergency was lifted in early 1977, and then the election took place. The moment the media came, The Indian Express launched its edition in Chandigarh in the first week of August. So, in July I got my first job at The Indian Express after I had worked at Democratic World. For my first appointment in the Express, my title was ‘Reporter – general and sports’. I was doing both things.

After resigning from The Indian Express in 1983, you joined the weekly magazine, India Today. How different was it to work for a magazine after working with a daily newspaper for six years?

I worked at the Express for six years -three years in Chandigarh and three years in the North-East. When I finished my three years in the North-East, it did look like I would have worked there. But then this opportunity came up from India Today with the intervention of Arun Shourie. He had recommended my name to India Today as it was expanding at that time. And I was hesitant because everyone said, “Why are you leaving a daily & going to a fortnightly?” It was then a fortnightly. Arun Shourie said that I need to work out of Delhi on the national stage. “You have done very well as the North East correspondent but you don't want to be out stationed all the time. Come to Delhi, and you will do a more diverse range of things”, Shourie said. And that's how I came to India Today in Delhi in 1983.

Initially, it was a big shift because in newspapers you write short stories, but in magazines, you write long descriptive stories. And India Today in those days would love to have 8000 to 10000-word cover stories. But nobody ever accused me of underwriting because I always overwrote! So that was quite useful. But I had good 12 years in India Today and I think that whatever you do, whatever you learn, you take that skill to the next thing that you do. So, I put my news sense from a sharp daily like The Indian Express to a fortnightly magazine. And then I learned the idea of packaging, descriptive writing, and in-depth journalism from India Today, and took that to the Express when I returned there. I found that over time, daily newspapers cracked the magazine code and that’s why magazines have become less and less important and powerful now.

Initially, it was a big shift because in newspapers you write short stories, but in magazines, you write long descriptive stories. And India Today in those days would love to have 8000 to 10000-word cover stories. But nobody ever accused me of underwriting because I always overwrote! So that was quite useful. But I had good 12 years in India Today and I think that whatever you do, whatever you learn, you take that skill to the next thing that you do. So, I put my news sense from a sharp daily like The Indian Express to a fortnightly magazine. And then I learned the idea of packaging, descriptive writing, and in-depth journalism from India Today, and took that to the Express when I returned there. I found that over time, daily newspapers cracked the magazine code and that’s why magazines have become less and less important and powerful now.

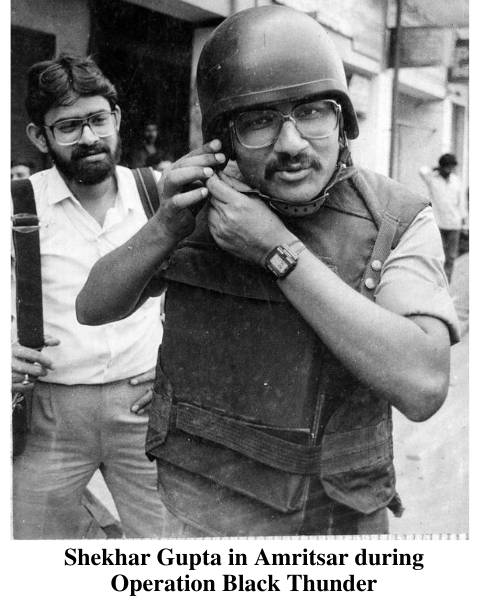

As a journalist at The Indian Express, and later at India Today, you covered a lot of conflict zones in India like the North-east or Operation Blue Star, and overseas too – Sri Lanka, Afghanistan, or Pakistan among others. While it did seem exciting, how did it change you as a journalist and influenced your idea of India?

The idea of India evolves. What evolved is something that I have written about many times. And I speak about it all the time too. That’s what I call the ‘bell curve of insurgencies in India’. Separatist movements in India follow a bell curve in India.

As separatism or violence increases, the state response also increases. And at some inflection point on the curve, the insurgents or separatists realize that no matter the number of bodies on the ground, this state is too powerful to give in. So, they are willing to settle, at which stage Indian states have always been willing to settle by giving some concessions, trading a few things, etc. North-east is a good example of that. It hasn’t worked everywhere. It didn’t work in Punjab; it wasn’t even tried in Punjab. And it hasn’t worked in Kashmir yet. But ultimately this is what works, and I think that’s how it will work with Naxalites also in Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand. That understanding came with experience.

As separatism or violence increases, the state response also increases. And at some inflection point on the curve, the insurgents or separatists realize that no matter the number of bodies on the ground, this state is too powerful to give in. So, they are willing to settle, at which stage Indian states have always been willing to settle by giving some concessions, trading a few things, etc. North-east is a good example of that. It hasn’t worked everywhere. It didn’t work in Punjab; it wasn’t even tried in Punjab. And it hasn’t worked in Kashmir yet. But ultimately this is what works, and I think that’s how it will work with Naxalites also in Chhattisgarh and Jharkhand. That understanding came with experience.

The other thing, very strange, when I was covering disturbances in India, it looked like India will go from bad to worse, to worse, to worse. But the fact is that India has gone from worse, to less bad, to less bad to better. So, there's a certain resilience. I think Indian nationalism has evolved over these four decades in a very healthy way. Although, some of the things that have been happening right now, it looks like we are trying to reverse it by creating a one land, with one faith, and one concept of Indian nationalism that is not needed for India.

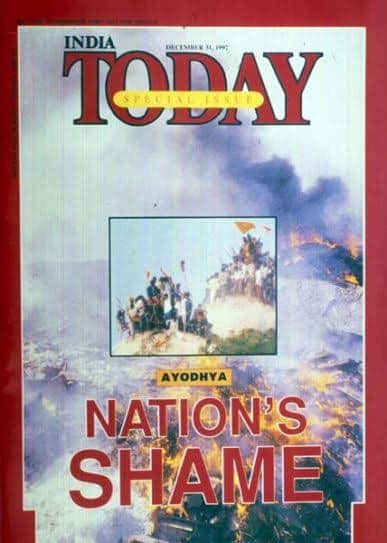

Recently in a tweet, you stated that when you were the editor of the Gujarat edition of India Today, the December 1992 edition received a lot of flak for its cover. Four weeks later, the readership dropped to mere 25000 from 75000, and the edition died -just like your marketing head had predicted.

I used to head all the language editions of India Today in addition to my work at India Today - English. So, India Today then had additions in several languages - Hindi, Tamil, Telugu, Malayalam, and I then launched the Gujarati edition. When I got that position, I also inherited the other four editions that were already there. I launched the Gujarati edition around Navratri in 1992. That is when Sheela Bhatt, who we had appointed editor of Gujarati edition, took me to meet Narendra Modi for the first time. He did not have any official position then. He was not even an MLA. And I was only going to Gujarat for getting to know people and understand things.

When Babri Masjid was destroyed, India Today's cover headline was the ‘Nation's shame’. There was an equivalent headline for Gujarati, I don't remember it exactly, but it was 'Desh nu Kalank’, I think. Our marketing head then, Deepak Shourie, who is Arun Shourie's brother incidentally, he said, “Look if you do this, people of Gujarat will not forgive you. You will suffer badly.” I must say that credit for this belongs to Arun Purie, because this was said in front of him. Arun Purie said, “it does not matter, let's go with it”. But we were surprised by the kind of sharp reaction that we saw. Because this is 1992 - there is no email, no social media. If there was email or social media, God knows what would have happened! In the next couple of days, I began getting a lot of letters, postcards - because they were the cheapest, a lot of them inland letters - I am not sure if people of your generation have seen those inland letters. They all were saying, “You are Pakistan Today”, “You are Islam Today”, “You are Musalman Today”, “Shame on you”, “Kalank on you”. I think the edition was pretty much dead. It survived for some more time, at least till I was in the India Today group until 1995, but not much longer.

When Babri Masjid was destroyed, India Today's cover headline was the ‘Nation's shame’. There was an equivalent headline for Gujarati, I don't remember it exactly, but it was 'Desh nu Kalank’, I think. Our marketing head then, Deepak Shourie, who is Arun Shourie's brother incidentally, he said, “Look if you do this, people of Gujarat will not forgive you. You will suffer badly.” I must say that credit for this belongs to Arun Purie, because this was said in front of him. Arun Purie said, “it does not matter, let's go with it”. But we were surprised by the kind of sharp reaction that we saw. Because this is 1992 - there is no email, no social media. If there was email or social media, God knows what would have happened! In the next couple of days, I began getting a lot of letters, postcards - because they were the cheapest, a lot of them inland letters - I am not sure if people of your generation have seen those inland letters. They all were saying, “You are Pakistan Today”, “You are Islam Today”, “You are Musalman Today”, “Shame on you”, “Kalank on you”. I think the edition was pretty much dead. It survived for some more time, at least till I was in the India Today group until 1995, but not much longer.

What made you go ahead with the cover regardless of the projected flak?

Because you know, this is a question I was asked once by Arvind Kejriwal, when The Indian Express was the only paper that was seeing problems with the Anna movement and India Against Corruption movement. We saw it purely as a political movement. We said that this has no interest in the Jan Lokpal bill. Because that bill is impossible, it is a North Korea bill and it cannot be passed in India. So, he did ask me and he said, “Have you asked your marketing department, how is the line that your paper has taken on our movement, working in the market?” And I said that we cover the news. We are not producing a Bollywood film that we have to have a hit. We are not producing a TV serial that has to have top TRPs. We produce news. We can go wrong with our understanding. But to the best of our knowledge and intentions, once we believe something to be the news, then it doesn't matter if it sells. But the fact is that while the Gujarati edition may have suffered, the Hindi edition with the same cover headline increased circulation greatly. So, I have used this example frequently to try and feed into the analysis of why Gujarat is very generous in a way that there is an insecurity about Muslims. That is also why Gujarat is such a fertile land for Hindutva.

(More on The Indian Express coverage of Anna Movement is covered in the next part of the interview)

What was the reaction from the administrative heads when the edition eventually shut down?

They didn't bother. I have to say that Arun Purie didn't bother. I think he took it in a stride. Nobody likes a product going down, but I think, it was okay. If you look at those issues of India Today, they took a very good position on that issue at that point. And he was very proud of it. The edition was not shutdown while I was there but this was only an additional charge for me. My main work was with the India Today English - my writing, my editing. I was running a lot of sections there. But as an additional charge, I was also running the language additions. I have two titles in India Today. I am used to having two titles. So, I was Senior Writer in India Today English and Executive Editor and Publisher with all the language editions. It was sometime after I left, that this edition was shut down. Then, I think as we know, in 2014 or 2015, the remaining editions were also shut down, besides the Hindi edition which is still there. I regret greatly that these editions had to be shut down but the reality is that the market, plus people who are running the business, know what is best for them.

Not many people know about the paper you wrote for ADELPHI, titled ‘India Redefines its Role’. You talked about India’s internal dynamics in the paper and anticipated BJP’s ascent to power based on their politics of giving a minority complex to the majority. Looking back at it, what do you think about the paper today?

ADELPHI is a set of papers published by the International Institute for Strategic Studies in London. I was a research associate there between 1993-94 on sabbatical. There is a section in the paper that talks about how a majority acquires a minority complex. That went to the question of how do Hindus, who are more than 80% of the Indian population, acquire a minority complex. There were many pointers at that time, but the fact is that there was a minority complex. When Mr. Vajpayee came to power – the first time, when he lost power in 13 days - in his reply to the Lok Sabha debate in a vote of no-confidence, he quoted this paper, “Aap ko sochna chahiye ki majority and minority complex kyon ho gaya hai.” He said it not by way of endorsement, but with anguish. And as you saw with this Ram Mandir thing, the majority does have a minority complex, and it is not as if this is the only country where this is happening. This has happened in other countries too.

It's a complicated set of factors if you look at it on the simplistic side. The explanation is simplistic - the majority Hindus were ruled by minority Muslims for more than 700 years. So, what do you expect? That India was always a majority Hindu country, but India's rulers were the Muslims. Many of them had come from overseas and they ran an Islamic system. There was jizya for Hindus for all those hundreds of years, barring 100 years - starting with Akbar and ending with Shah Jahan.

So, there are such issues, but also, it's a question of how do various parties play their politics. The BJP worked on this minority complex to woo the majority. Congress party, I would say that from 1986 onwards played into it. Indira Gandhi would have never allowed it, but Rajiv Gandhi made mistakes - Shah Bano case, the proactive ban on Salman Rushdie's book, played into it.

Part 2 of this three-part interview ca be read here. Part 3 can be read here.

(Kartavya is celebrating its first anniversary on 9th August. On the backdrop of this special occasion, we will publish comprehensive interviews of three renowned editors of English journalism for seven consecutive days starting today, that is, August 9th to August 16th.

N. Ram's interview has been published in three parts and sheds light on the past and present of The Hindu. Naresh Fernandes' interview has been published in two parts and talks about Scroll.in. And lastly, Shekhar Gupta's interview has been published in three parts which will address his career with The Indian Express, India Today, and The Print. Although these editors belong to three different generations and have a differing point of view on some issues, their commitment to the core values of journalism is alike.

The Marathi translation of this interview has been published in the 15th August 2020 edition of weekly Sadhana.)

Tags: shekhar gupta the indian express jayali wavhal interview journalism Load More Tags

Add Comment