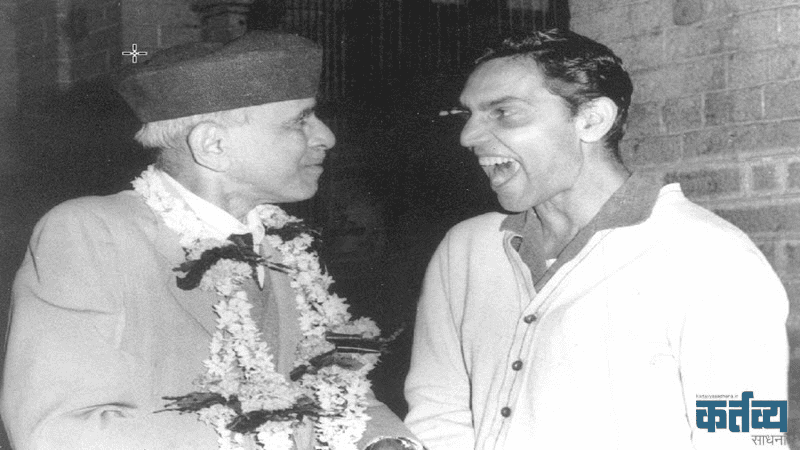

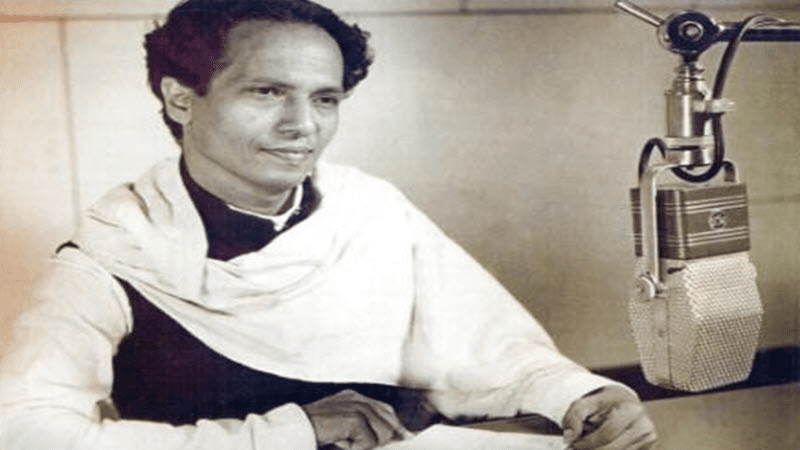

Hamid Dalwai, who lived a short life from 1932 to 1977, was able to dedicate a quarter of a century to public life. In the first half, he was recognised for his fiction and opinion pieces, while in the second half, he established himself as a Muslim reformist and thinker. Today if you list people whose vision and action is crucial to make India, not just the Muslim society, more modern, progressive, and secular, it is impossible to overlook Hamid bhai's name. Many have written about the views and actions of Hamid Dalwai. But this walk down the memory lane that his younger brother Hussain Dalwai took some 42 years ago, is unique. It provides a rare glimpse into the formative years of Hamid Dalwai.

Author Husain Dalwai has spent 50 years in public life. A leader of the Congress party in the state, he has been a member of the Maharashtra legislative council as well as the Rajya Sabha.

Hamidbhai, who was full of love for his village, wrote a will that specified: 'After my death, do not take me (my remains) back to my village'. That a man, who was once so immersed in the village and its surroundings, felt compelled to write so, indicates how strongly the relatives and fellow Muslims back home were opposed to his views.

To understand the power of his rebellious creed, one must first understand the village atmosphere where he grew up. Honestly, it pains me to write about him like this, posthumously. I should have penned my memories of him a long time ago. The world now recognises Hamid Dalwai as a thinker and an author. But few people knew him as a person. Therefore, I often felt, I must write about him. Alas, I missed the moment. Had I written about him when he was alive, it would have been with a different viewpoint.

Hamidbhai's life is packed with incidents, and enriched by them. If I were to string together all these events, it will require preparations of biographic proportions. Which is neither the intention nor does time permit it for now. In this piece, I shall therefore briefly relate incidents from his personal life.

Hamidbhai was born in Mirjoli - a small village near Chiplun. Our father married four times. Hamid (Dada as we used to call him) was born to our second mother. Our eldest mother was issueless. So she took the initiative in arranging our father's second wedding (to a close relative of hers). Our father was 40 at that time, and the bride... barely 15 or 16. She was extremely beautiful. So I have heard, of course, from our father.

Unfortunately, she died at 18. Tuberculosis brought on the end. Father moved heaven and earth for her treatment. He even rushed her to the hospital at Miraj. But tuberculosis was untreatable at the time. When she died, Dada was just two. A few years later, our eldest mother too passed away. Father married for the third time. The third wife gave birth to four children. I was born after my three sisters. My mother too passed away when I was just two or three.

Father married for the fourth time. Dada (Hamidbhai) was then in Mumbai. He expressed opposition to Father's fourth wedding. But he was not earning at the time and depended on our father. The latter therefore did not pay heed to Dada's opposition. Our fourth mother gave birth to two boys and three daughters. Except for Dada, I and all my siblings were born to our father when he was old. He appeared more like a grandfather to us. He too passed away in 1971.

None of us ever felt like step-siblings to one another. Dada was the eldest. The responsibility of all of us younger siblings fell on his shoulders. And he lived up to it, till the day he left us.

Our father traded in roof tiles. In 1956, the business suffered a setback and sank. The family fell on very bad times. Father had expanded the family in size, and Dada had to bear the brunt. Dada too contracted tuberculosis in 1952. He was also down with typhoid once. He had to throughout battle with several health issues. But when the kidneys were affected, he could see the end. "I would have died of TB long ago. But streptomycin came to India in 1950, and gave me an additional 24 years to live. Not a small thing that. I feel I've lived so long."

Our immediate family history must have prompted him to think about making polygamy preventive laws applicable to Muslims too. In his prime years, Dada was an ardent follower of Dr. Ram Manohar Lohia (iconic socialist). Dr. Lohia said, "... a man who loses three wives one after another and then marries a fourth... cannot be a good man. It's rare that three wives die of natural causes. It mostly happens due to neglect and poverty."

Similarly, Dada must have also been introduced to the notion of family planning. He saw an ageing father continuing to expand progeny. He saw his married sisters getting pregnant almost every year. And then, he saw the plight of their children. He needed no degree in sociology to understand the importance of family planning.

Dada did attend school, but can't say he studied a lot there. He failed for the first time in the eighth grade. When his second attempt was due in the subsequent year, he ran off to Mumbai. This caused panic in the family. By then, the father was well-versed with the boy's nature. He guessed Dada must have run off to Mumbai. He went there and convinced Dada to return home. The next year, he cleared the eighth-grade exam. Instead of studying at school, Dada much preferred going to the Lokmanya Tilak library and reading up on literature and history.

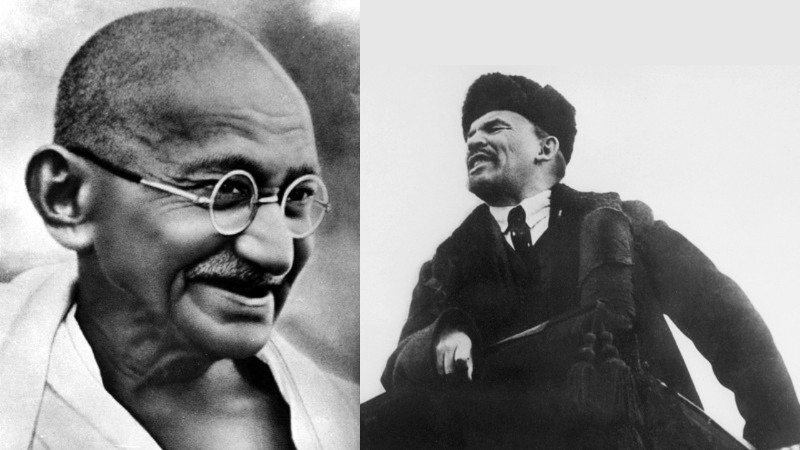

While still at school, he started attending Rashtra Seva Dal meetings. When the Muslim mind was so mesmerized by the call for Pakistan, Dada used to chant, "Mahatma Gandhi ki Jai" (Victory to Gandhi). When the village boys were signing up for drills at the extremely fanatic outfit Muslim Guard, Dada was picking up the norms of social service at Rashtra Seva Dal.

Once, the Muslims from our village organized a fete at the local school, on the occasion of Eid-e-Milaad. Slogans of 'Pakistan Zindabad!' rented the air. Actually, the occasion was religious. Why have politics? But Muslims do not segregate religion from politics. In that case, why have only one kind of politics? With that thought, Hamdbhai and his friend Deshya (who now works with Maharashtra state road transport or ST) gave cries of "Inquilab Zindabad" "Mahatma Gandhi ki Jai". This kicked up a storm at the gathering. People bashed up Deshya. Dada escaped the beating. My father and a few local Muslim League leaders were also present at the event. For the next 10 days or so, Dada did not face up to our father.

Dada was embroiled in many such conflicts in the village, and people would pounce upon him. Many of them would be our relatives... belonging to different political parties. All of them would unite if it was 'Hindu-Muslim' argument. Dada seldom found any supporters in the village. A few youngsters were attracted to his ideas, but they posed no challenge to the fanatic leadership.

In 1974, Muslim women were to hold a conference in Chiplun. Fanatics in the village roped in henchmen from the hooch trade to overturn Dada's vehicle in the Parshuram Ghat (mountainous section). Luckily, Dada had left a day in advance, and 'accidentally' escaped this sabotage. Not ones to be stopped at that, the henchmen stopped the bus ferrying the women delegates. They harassed the delegates and hurled stones at them. One of our sisters too was injured in the attack. Such was the terror unleashed by the henchmen that many of the attendees from neighbouring towns and villages also ran away.

People of the village were opposed to Dada not just over 'Muslim' issues. There were other reasons too. Let me cite two examples here to give you the bigger picture.

While Dada was at school, the village faced a great shortage of kerosene due to World War II. Muslims of Mirjoli were khots or collectors of land revenue - more affluent than the rest of the villagers. Over the years, they exploited the neo-Buddhists, Dalits, Kunbis, and even Maratha landholders, and amassed much wealth. Muslim khots till date exploit the Dalits in many ways.

The khots also ran the government fair-price shops in the village. When Dalits and Kunbis came to collect their monthly rationed quota of kerosene, the khot used to turn them away, claiming there were no stocks. As a result, while the Dalits and Kunbis were forced to spend the nights in the dark, the Muslim quarters would be well-lit with the stolen kerosene.

When fair means did not yield results, Dada organized the Kunbis and Dalits, and decamped with kerosene containers, and upturned any remaining stocks. This enraged the shop owners but they could not complain because the entire stock was misappropriated.

Much of the cultivable land in the village belonged to the Muslims, who further sublet it to the Kunbis for tilling. The khots used to collect half of the produce as revenue. Prior to the land-to-the-tiller movement, a law was passed reducing the khot's share to one-third. The Khots were obviously not amenable to this. They started using strong-arm tactics with the tillers to yield half the share.

Dada was unwell at the time and was resting in the village when the kunbi tillers approached him for advice. Naturally, his advice was to abide by the new law and submit only a third of the grain to the Khots. This further enraged the Muslim Khots.

Obviously, Dada's views on religious reforms within Muslim society did not go down well with the community. Till his dying days, he remained conscious of the fact that his family would be targeted because of his views. He, therefore, wrote a will about a month before his death, and ensured it would be properly executed. If his mortal remains were taken back to the village, the will would not be fulfilled. The will incidentally invoked further wrath of many of our relatives back home.

Upon completing matriculation, Dada moved to Mumbai. He roamed frantically in search of work. That's when he too, unfortunately, contracted tuberculosis. He started writing his short stories in those days. The story of an unemployed yet artistic man, 'Bekar pan Kalawant Mansachi Goshta', which is part of his collection, Laat (Wave), was based on his experiences from those days of joblessness. No job, no home.

Once I passed the seventh grade at school, Dada also brought me to Mumbai. In Mumbai, we lived at the residence of one of his friends, Jaffar Khan, who was married to a Hindu woman. Jaffar Khan's family returned to Mumbai after three months. While they were an affectionate family, it was impossible for so many people to live in a two-room tenement. We, therefore, moved in with a relative, who lived in a hut in the slums of Kandivali. Life in the slum was scary.

I was not used to the Mumbai way of life. In the rains, ants, earthworms, and even snakes found their way into the hut. The ground underneath would sweat like a swamp. Our young sister lived with us. There were hooch shops near the hut. I found it difficult to continue living there. Everything, from going to the toilet, was a big problem. The morning began by borrowing a few annas from Dada's pocket and making arrangements for tea and some bread. This was followed by the struggle to get enough money for lunch. My schooling was long discontinued. My kidneys were affected during that time and I was sent back to the village. My kidney ailment rescued me from the hell that was the slums.

Our father was forever after Dada to get married. He received various proposals from Mirjoli. But Dada's reply was firm "No marriage for me." Which was not true though. My sister and I were aware that back in Mumbai, he had fallen in love with a Hindu girl. But when he finally agreed to marry, it seemed like a different girl. Our father was not opposed to the wedding. From the picture, we all thought she must be Hindu. We were overjoyed to see her picture. Even before the wedding, our father put her picture on the wall. This was unusual for Muslim homes.

After the wedding, Dada brought his newly-wed bride to the village. For the next eight or ten days, our home overflowed with joy. Everybody approved of the new addition to the family. We had no electric power in the village then. According to our new bhabhi (sister in law) the kerosene lamp made no dent in the darkness. Once or twice, she spotted a scorpion. That made her too afraid to step down from her bed. We were all so amused.

After completing my tenth grade, I returned to Mumbai. Dada had moved into a single-room tenement in the Majaswadi area of Jogeshwari, by then. I, Dada, bhabhi, Rubina (daughter), Fatima (sister) made that single room our home. Bed bugs, mosquitoes, and sultry weather were part of the parcel.

Dada had gotten a job with the railways. But he lost it soon for having participated in a worker's strike. Some folks from Mirjoli ran trucking businesses in those days. It caught Dada's fancy. He borrowed some money from a maternal uncle and brought a truck from the scrapyard. That episode had much resonance with Chi Vi Joshi's humorous tale 'Junay te Sonay' (Old is Gold).

There is enough material to write an article on that truck someday. Every day, at least one part of the truck used to break down. Especially around payday for Bhabhi some big fault would turn up. A crack in the steering...a radiator or tyre burst, or a broken clutch plate or axle became a regular feature of the truck. Dada would send me to Bhabhi's office. She would have received her pay packet, from which she would hand over a sum for repairs to me. Her office colleagues used to give us strange looks.

Mirjoli truck owners business practices included exploiting labour, holding off drivers monthly dues, manhandling workers, and using foul language. That was not Dada's cup of tea.. and he ended up loaning money to his staff instead. This was clearly no business for a sensitive man. Finally, the truck ended up with a Pathan moneylender, who broke it down and sold off the spares. The truck piled up a loan of Rs 10,000 to 12,000. Dada spent the next 10 years, paying it off in instalments.

We moved from the room in Jogeshwari to a live-and-license arrangement with a Muslim landlady at Jaya Terrace, opposite Hindmata theatre, in Dadar. Within eight days, the landlady gave us the marching orders. Dada had sold off the Jogeshwari room by then. After her morning namaz, the landlady would raise her hands to Allah, and pray for bad things to befall our family. This was followed by an hour of hurling choice abuses at us, all in the name of God. This was most painful for Dada and bhabhi.

Dada started looking for a job again. He had just returned from a study tour of Pakistan. His friend Ashok Padbidri managed to pull a few strings and got him a job at Maratha newspaper. The paycheque was for Rs 225. Dada was thrilled. His articles in Maratha were a great hit. He was also able to return to his favourite literary field. His novel Indhan (The Fuel) was published around that time.

He was a man at peace with himself during those days. He used to be happily self-absorbed. He used to jokingly say to his wife, "Don't underestimate your hubby. He is on his way towards winning a Nobel. Only two people can win that prize in India. The first is Rabindranath Tagore and the second is Hamid Dalwai."

We were all so proud of Dada. He used to be in his own trance. If he started discussing cinema, he could go on for two hours. If he spoke about music, he could fill the room with music. Mahabharat, World War II, and General Rommel, were three topics of great interest to him. Later, his talks centred increasingly around Muslim issues.

I am yet to meet a person with a sharper memory. I do not say this as his brother: It's a fact. His memory was photographic. Every incident would dance before his eyes. Failing thrice to clear intermediate school therefore never proved a stumbling block for him. He rarely spoke English, but 95 percent of what he read was English books. And he could read at great speed. He once wanted to gift a copy of Maxime Rodinson's 'Muhammad' to a Marxist editor of an English language weekly. I was instrumental in fixing that appointment. When the book fell in our hands, there was a day left to the meeting. Dada finished reading the 250 pages of the book in a day, and presented it to the editor.

His popularity grew in his later years. But even those who hailed him, failed to understand him completely. Some people were tickled that he spoke about Muslims. Dada was not oblivious of them. He used to sometimes speak openly about this. At the Amar Hind Mandal in Mumbai, the audiences faces lit up when he spoke about issues facing Muslim women. He, therefore, concluded by saying. "I do not mean to say that these issues are resolved for Hindu women. As long as marriage remains an institution to subjugate women, as long as the society does not give women the right to bear children without a husband, I will never agree that women are liberated..." This last sentence wiped off the glee from the audience’s face.

(Appeared in Weekly Sadhana, edition dated May 14, 1977)

Post Script

It's been 40 years since Hamidbhai passed away. Much water has flown in the rivers ever since. Much research has been published around the Islamic faith and society. Hamidbhai did not have the benefit of this research.

The question of verbal divorce (Jubani talaq or triple talaq) that Hamidbhai first raised, has now come to the fore. Except for some ultra-orthodox elements, a more conducive atmosphere exists towards the issue. That is, there are increasing voices within the community, for the abolition of triple talaq.

Muslim society has also undergone a transformation. Muslims have started taking a more firm stand on the formation of Pakistan. They realise that the formation of Pakistan was detrimental to them. More Muslims today feel that the community should have stood more firmly with Maulana Azad's principles.

It is time to accept that Muslim community is religious, and then appropriately place your thoughts before them. In this, it is best to follow Mahatma Gandhi's policy. Hamidbhai subscribed more to Agarkar's rationalist path. I had my differences with Hamid bhai over this. He used to say to me, "You look at the world through the socialistic lenses of Yukrand ." But there was never any room for Jinnah's two-nation theory in his rationalist path. He was emphatic that Jinnah and Savarkar were both progenitors of the two-nation theory.

Today, at an international level, there are many thinkers and their commentaries, that raise the issues facing the Muslim society. These are now accessible to us due to globalization. In such times, I truly miss Hamidbhai who spoke so intensely about Muslim issues.

(When weekly Sadhana, re-ran Husain Dalwai's original memories of Hamid Dalwai, after 40 years, Hussain Dalwai added the above post script)

(Translation by Sanjay Pendse. Read Marathi version of the article on Sadhana Archive)

Tags: Husain Dalwai Muslim Reform Islam English Load More Tags

Add Comment