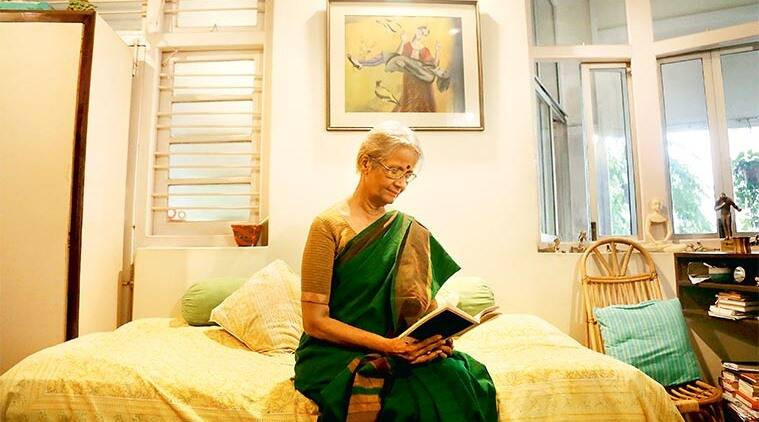

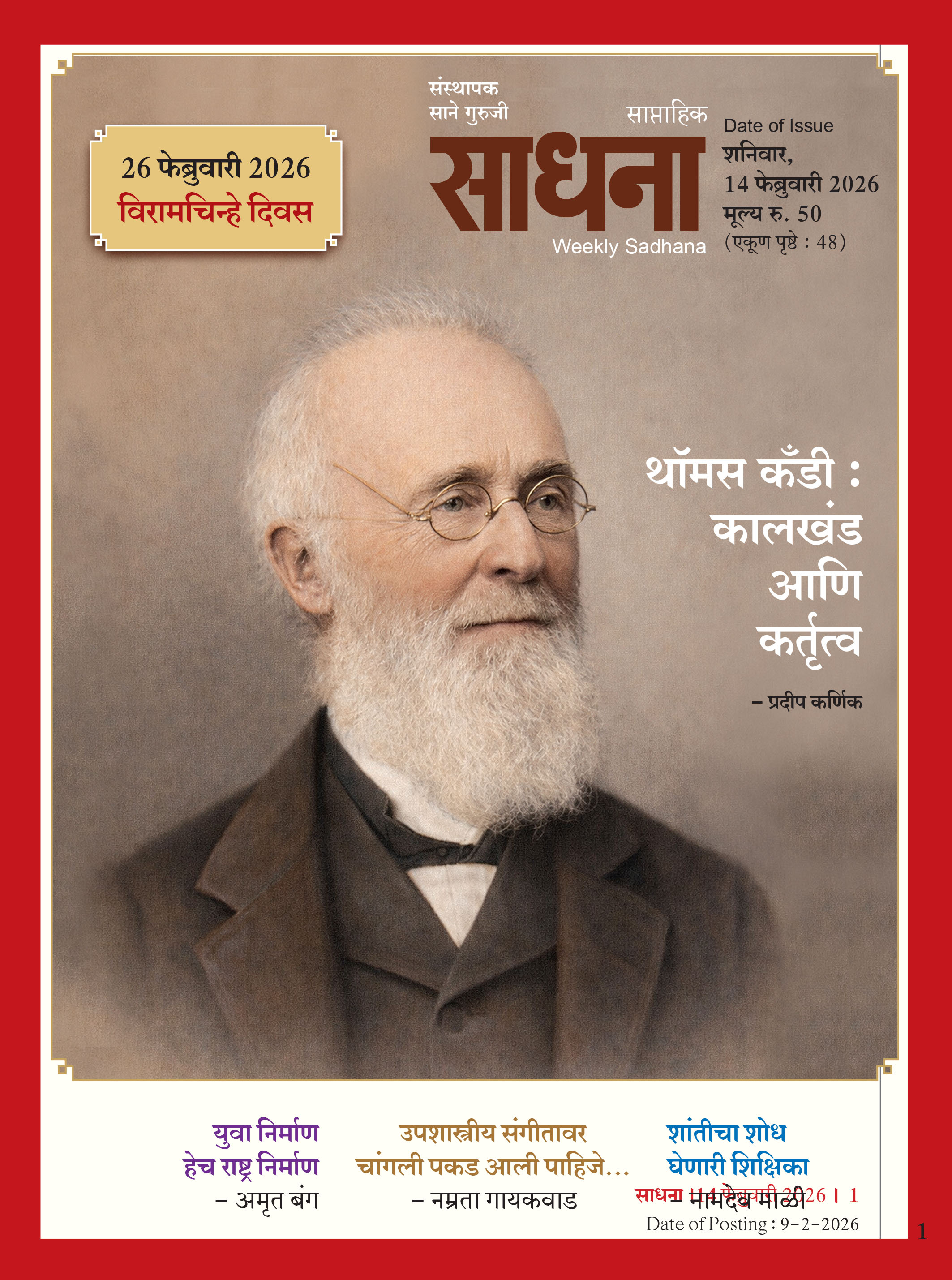

A chance call by the editor of reputed Marathi weekly Sadhana, caught me off guard. He wanted me to interview Shanta Gokhale. He said she had recommended me for this task. I felt honoured and a wee bit uneasy.

I have known Shantatai for a while now, more as a scholar, writer, translator, and iconic figure in our world of theatre. Her contribution to bringing literary works in Marathi to an English-speaking audience has been immense. Probably one of those few who have bridged the divide so effectively.

My first interaction with her was at the theatre space Adishakti in Auroville, in 2005, where I was shortlisted for a translators workshop, along with 4 others, who had been writing on theatre from regional languages to English, while she was one of the mentors along with Alok Bhalla, Girish Karnad, Veena Pani Chawla and others. I was mesmerised by her expansive experience and passion regarding translations. Her guidance and inputs helped me make my own little contribution in this field by translating Vijay Tendulkar's children's plays into English, Sachin Kundalkar’s Poornaviram, Makarand Sathe’s Golayog.com and Teh Pudhe Gele, along with a string of others.

Over the years we met at times at theatre festivals or related occasions, but these meetings were restricted to cursory greetings and acknowledgment. Though wanting to, I didn’t attempt to engage in further talk, as she was often swarmed by well-wishers. And now this chance to interact with her, though unfortunately only by mail.

Over the years we met at times at theatre festivals or related occasions, but these meetings were restricted to cursory greetings and acknowledgment. Though wanting to, I didn’t attempt to engage in further talk, as she was often swarmed by well-wishers. And now this chance to interact with her, though unfortunately only by mail.

I have read all her translated plays and was always intrigued of how her words, dialogues, descriptive situations, so aptly arranged, would conjure images, which felt as if one is ‘watching the happenings ‘live! This feeling was great and very engaging.

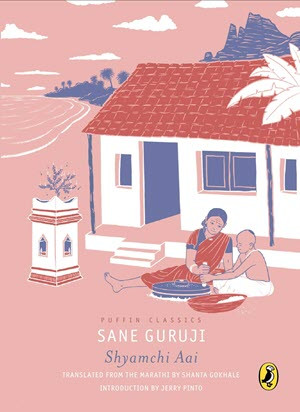

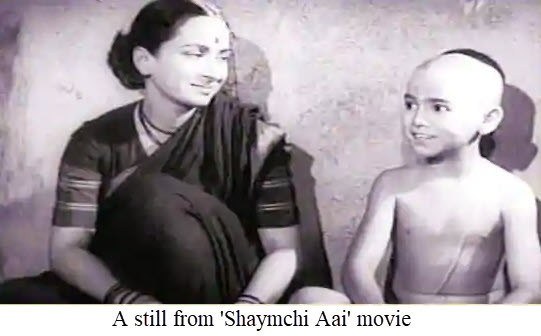

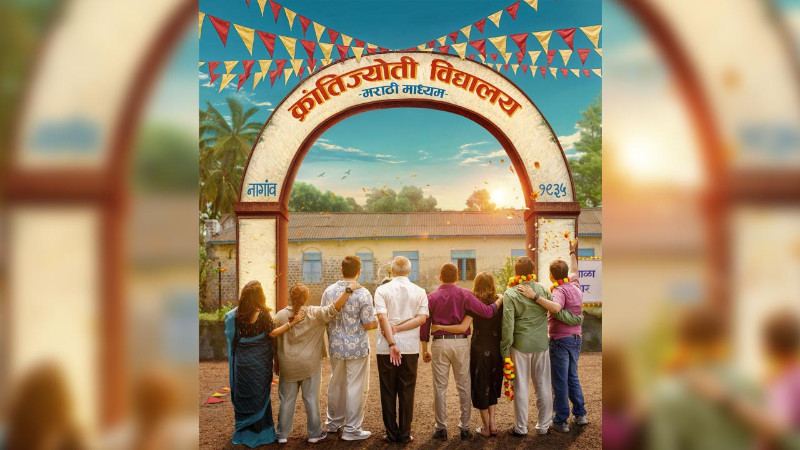

When I came to know that she had translated the extensively read ‘Shyamchi Aie’, I was curious. Not because I doubted her capacity to do so, but since this book was a classic, written decades ago, so different from the contemporary sensibilities, using a dialect that seemed strange to read and a book that had carved the lives of an entire generation. And this to be read in a different language, so rigid in this own syntax and demands.

As I turned the pages for the translated work, I was soon sucked into the fluidity of her work and the ease with which she navigates the reader through the text, while being in complete command over the chartered course. It is a project well accomplished and a definitive read. Many questions came to my mind and she indulged my curiosity on the process with her responses, establishing this translation as a classic in its own capacity.

Read on.........

What prompted you to do this translation-Was it because it was commissioned or were you drawn to it otherwise.

What prompted you to do this translation-Was it because it was commissioned or were you drawn to it otherwise.

I had always intended to translate ‘ShyamchiAai’. It was on my private list of to-do translations along with Lakshmibai Tilak’s ‘Smritichitre’ and S. V. Ketkar’s ‘Brahmankanya’. When Penguin asked me to do it, their request matched my wish.

Times have changed since it was first published in 1935 when today relationships and values have taken different meanings. With your vast experience over the years, you have seen the transition- how did you connect with the story from the contemporary lens.

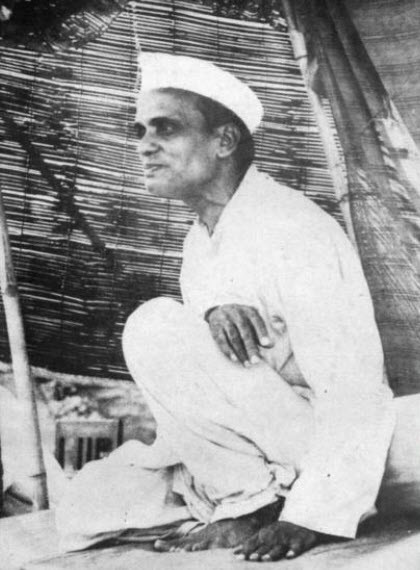

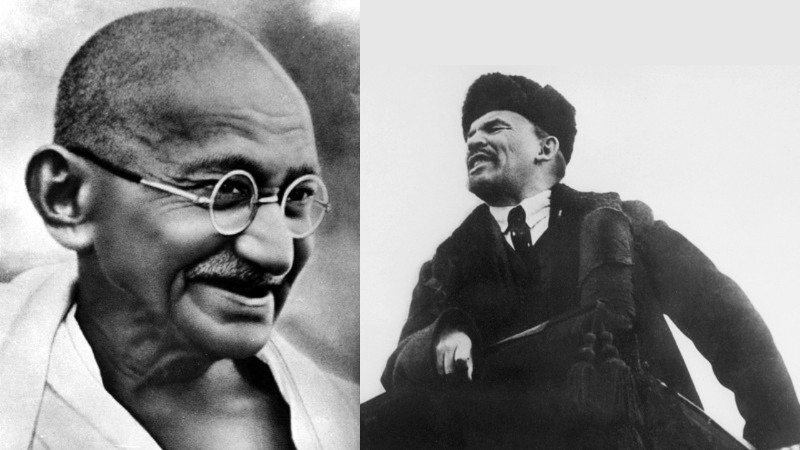

I found certain ideas difficult to digest. Cow worship was one of them. At any other time, I would have been fine with the genuine devotion with which Shyam’s mother worships her cow. But given today’s times when the sacredness of the cow is being used as a weapon to kill those whom the State wishes to repress, I felt it was treading on dangerous ground. As a woman, I felt angry at the way women were treated in those days. I was also angered by the arrogance of brahmins. And yet, the important thing for me was that Sane Guruji questions many of these values in the course of telling the stories. He leaves it to the listener or reader to decide what is right and what is wrong while guiding us to a humanistic, progressive view.

Were you ever worried how today’s generation would identify with the story- especially since the core of it is values, on which Indian societal structures are founded.

Like writers, translators too should not worry about how readers would respond to your work. And in this case, particularly, it doesn’t even matter. This book has been published as a classic. Classics aren’t necessarily read. They are venerated as the best works of culture.

As far as values go, the most important ones emphasised in the stories are or should be today’s values too. All of them are humanistic – respect for yourself and others, perfectionism in all you do, pride without arrogance, kindness, compassion, and, above all, love. Today’s generation doesn’t hear of these values either from parents, teachers, or so-called opinion leaders.

Parents and teachers whom Sane Guruji believes are the most important influences on a child’s mind are busy ensuring that their wards get 99 percent marks. Bright children get all the praise. A kind-hearted, generous child gets none. Men of money are respected. A poor man is not. Your statement that these are values on which ‘Indian societal structure is founded’ is far from the reality. Indian societal structure is founded more and more on money, commerce, and show.

I have read your translations of poetry and plays, as also some of the novels you have worked on. As a translator do you have any yardsticks in mind when you approach and start your work of translation?

I have read your translations of poetry and plays, as also some of the novels you have worked on. As a translator do you have any yardsticks in mind when you approach and start your work of translation?

I never translate a work that I do not care for deeply unless it is something a friend has written where the yardstick is different. The translation is hard work. If that work is not challenging and pleasurable, the translation and my own mental health are adversely affected.

When I am translating a text of my choice, I want to make sure that, were the author alive, s/he would not say to me, ‘This is not what I said’ or ‘This is not what I meant.’ If I have reproduced their unique voice in the translation, they will not say this.

If I am translating a creative text, I must first understand how the author is using language. There are differences between the Marathi used by Vijay Tendulkar, Mahesh Elkunchwar, Satish Alekar, G. P. Deshpande. Language reflects a writer’s feeling for it, a writer’s personality, and a writer’s worldview. So when I say I must understand how the author is using language, I am saying I must understand the sources from which her/his language spring. Only then will I dig deep into my own store of English to come up with the correct equivalents. As a result, I use words and expressions in my translations that I have not used in my own writing.

Each form of literature makes its own demands on the translator- what challenges do you face when you work on prose.

The prose is the least challenging of the literary forms I have translated. One of the challenges it might offer is dialect. This is tricky to translate. I know a couple of English dialects, but I cannot use them as an equivalent to a Marathi dialect. Even more deeply than standard language, a dialect is rooted in its own soil. If the Varhadi spoken in Uddhav Shelke’s ‘Dhag’ is translated into London Cockney, the images it will throw up will not be of poor men in dhotis and poor women in 9-yard saris but of pub-going men and women in slouchy caps and heels. My effort is to find a form of English that will suggest Varhadi’s departure from standard Marathi without using an alien dialect.

The particular challenge of plays is to catch the rhythm of the spoken word as used by the playwright. The language a playwright uses tells us of her/his attitude to the theatre of her/his times. Tendulkar is writing against the overstated wordiness of the mainstream stage. Alekar is undercutting sentiment with the ironic twists in his language. Elkunchwar’s language is distinctly rhythmic, often coming close to the poetic. G.P.D’s language is often a deliberate attempt at reviving words and ideas that he values in our culture and is sorry to see vanishing.

Poetry is the most challenging of the three forms. It leaves much unsaid. It deals in images, allusions, metaphors. They, more than words, add up to the ‘meaning’ or ‘sense’ of a poem. The translator is called upon to create a poetic response to them to catch this sense. That is a very tall order.

Most of your work of translation, has a fluidity in the narrative. It invariably conjures up visual images- as if watching a painting or film. That is very appealing and keeps one hooked. Is this deliberate or your style?

If my translation has that effect, it must have its roots in the original text. Unless I find an image there, it will not appear in my translation. As far as flow is concerned, perhaps my style contributes to that although, again, the original also has its own flow. The syntax and grammar in Marathi and English are different. In Marathi, the predicate comes first. The verb follows. Exactly the opposite happens in English. As a result, the translator has to reverse the order of words in the original to make it sound like English in the translation. This means the translator is rewriting the original sentence and will naturally do it in her own style.

Could this be a result of your long association with theatre, which demands you to create a picture for the reader- a style that has crept into your translations. And believe me, it makes the work so much more readable.

Once again, I must stress that nothing that does not belong to the original, creeps into my translation. If my translation is readable it is because I am faithful to the English tongue while being faithful to the original.

‘It is one of the chief precepts of our art that we do not translate words but worlds’. Would you like to elaborate?

Words are only symbols. When they are arranged in a particular order, they become meaningful. This meaning comes from various worlds – the world of ideas, images, of a culture, or even history and geography. Take the word घाट. It has two meanings, one connected to the geography of Maharashtra, the other to its culture. To translate the word correctly in its context we have to translate the world to which it belongs. Suppose a sentence reads, बायका कपडे घेऊन घाटावर गेल्या. We realise that they are not going up the mountain pass but are headed for the steps on a riverbank. But unless we know that people wash clothes on the ghats we will not be able to translate the sentence in a way that is meaningful to the reader. If we know it, we will slip in an explanatory word or two. We will say, ‘The women carried their dirty clothes to the river bank to wash them.’ This is a very simple example to illustrate my statement.

‘But for a few exceptions the translator must always stick to every single thing the writer has said.’- would you like to elaborate, in light of the new work travelling across cultural zones, specifically with context to language.

‘But for a few exceptions the translator must always stick to every single thing the writer has said.’- would you like to elaborate, in light of the new work travelling across cultural zones, specifically with context to language.

Being faithful to the original is my credo. Most other translators believe in it. Some translators have theories about the power equation between languages and how translators should show an awareness of this in their work. Since I am a practising translator, not a theorist, I stick to my beliefs about translation.

You have retained many original Marathi words, but no footnotes- what was this choice, especially since the reader may not be Marathi speaking. Would it lose its flavour and engagement?

The choice to retain original words with or without footnotes was made by the publisher. They have their own ideas about translation. I provided the footnotes when called upon to do so. And when they asked if I would mind retaining the original Marathi words in some cases, I was perfectly happy to do that too. People do gather meanings of strange words from their context. When I began reading the Russian novelists as a teenager, I didn’t know what a samovar was. But I soon learned.

A text written in the 30’s- the style of the original Marathi written then, was different and which has evolved over the years- was this any consideration during your translation- I ask this as some words used needed an explanation, as has been carried in the Marathi.

Working on a text that pre-dates the translation by several decades, you cannot return to its chronological equivalent in English. Like dialect, this would suggest a world very different from the Marathi world you are translating. However, using contemporary language would also not work. It would destroy the location of the text in our literary history. If I have two alternative words, I would choose the more formal of the two. This would still be contemporary but literary contemporary. The feature that marks writing of an earlier age, whether in Marathi or English, is a formality of expression. Literature was held to be apart from everyday speech. Today literature is closer to everyday speech.

This story has always been associated with overt sentimentality and heightened melodrama, as was also seen in the film based on it. Yet you have skirted that temptation in your translation. About this choice.

This story has always been associated with overt sentimentality and heightened melodrama, as was also seen in the film based on it. Yet you have skirted that temptation in your translation. About this choice.

I have done this very consciously. The Marathi world is sentimental. I have said that worlds, not words are to be translated. But one must bear in mind that what you want is a positive response to the book in translation. If it is going into a world that is opposed to sentimentality, the book will not be loved as it has been in its home country. The point of translating it would then be lost. Jane Austen wrote an ironic novel, ‘Sense and Sensibility’ about the over-sentimentality of women in her times. That was two centuries ago. Now sentimentality is even less acceptable in the west.

In translation how much liberty do you take to explain at length, tightly structured sentences in the original, which might require elaboration in English? Especially since you master both languages.

I take just enough liberty to make meanings clear. I also take the liberty to split very long sentences into short sentences. The way syntax works in Marathi, a whole series of clauses can precede the verb. This is not possible in English. So I chop up compound sentences into more simple structures.

At times you have to delete text from the original, as the cultural transition becomes very difficult to negotiate. About that.

In the case of ‘ShyamchiAai’, I had deleted nothing at all in the translation that I submitted to the publisher. But they suggested deletions. For example, they thought readers would not be held by the list of eminent men from Dapoli district which Sane Guruji gives to underline its importance. The publisher suggested we drop those names from the body of the translation and expand on the names in the extras at the back of the book. Readers would then get more than just names. They would know who these men were and what they did in life. Deleting is not necessary. There is no such thing as not being able to negotiate cultural transitions. That’s what translators do. It is their job.

Each story ends with a value-based conclusion...

Yes. They are morality tales and like all stories belonging to this genre, the moral of the story is underlined at the end. In this case, it throws up the main issue of the story which teachers/parents can discuss with children.

Often one gets the feedback that the translation reads afresh- like written for the first time. Would you take this as a compliment or a setback on staying loyal to the original script and the writer’s words?

I take it as a compliment. Translators are writers. It is their words that the readers in the target language read. The hard work involved in translation is precisely about attaining a balance between fidelity and readability. I am often told that a translation of mine reads as though it was originally written in English. And I say thank you very much.

Intrerviewed by Dr. Ajay C. Joshi.

journo.ajay@gmail.com

(Dr. Ajay Joshi is a practicing dentist, with a Ph.D. in Theatre Criticism and Masters in Journalism and Mass Communication. He is a published author and has been the recipient of the prestigious Fulbright Fellowship for 2018-19, teaching theatre at Rutgers University, USA.)

An interview with Shanta Gokhale, the English translator of 'Shyamchi Aai', by Mrudgandha Dixit in Marathi can be read in the February 27, 2021 issue of Sadhana Weekly. - Editor

Marathi and English Versions of the book 'Shyamchi Aai' are available at Sadhana Media Center, Pune. Also available on Amazon.in

Tags: Shyamchi Aai Book Sane Guruji Shanta Gokhale Dr. Ajay Joshi Load More Tags

Add Comment