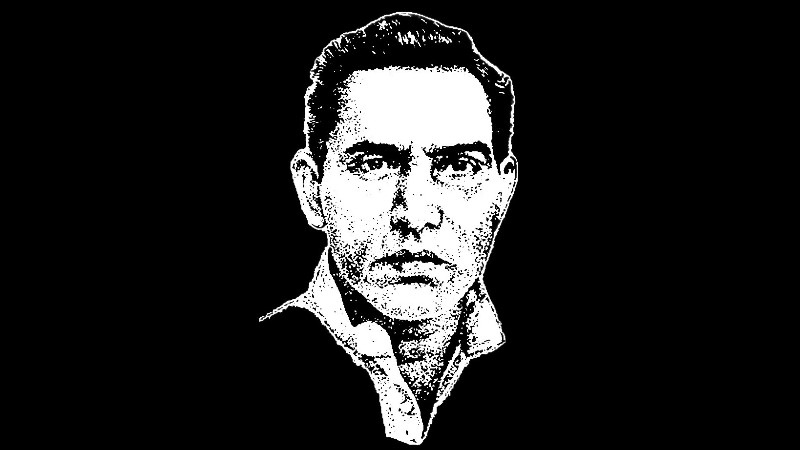

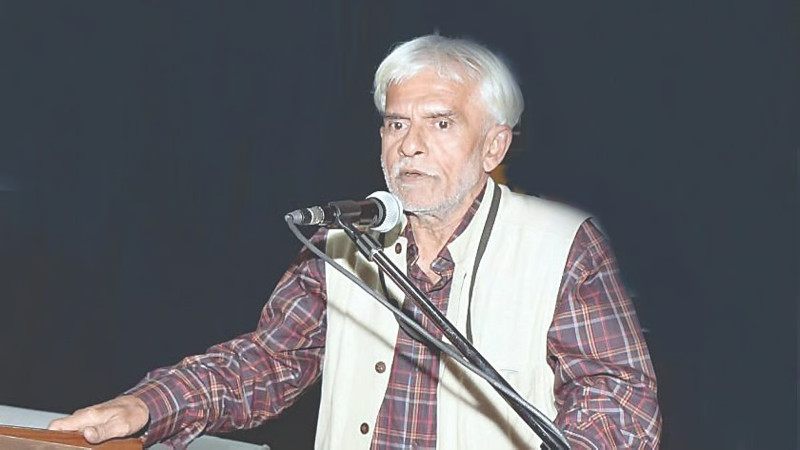

Hameed Dalwai, who lived a short life of just 45 years, had a public career that spanned over a quarter of a centuray. Yet, within that brief period, he established a significant national presence, forging a dual identity as both a writer and an activist. His literary and intellectual contributions, though limited in quantity, were deeply transformative. At the same time, he spearheaded a movement dedicated to the reform and awakening of the Muslim community. Today, on September 29, 2024, we commemorate the 92nd birth anniversary of Hameed Bhai. In honor of this occasion, we are publishing the English translation of his Marathi essay "Mumbaikar Muslim," written 60 years ago, when he was just 33 years old.

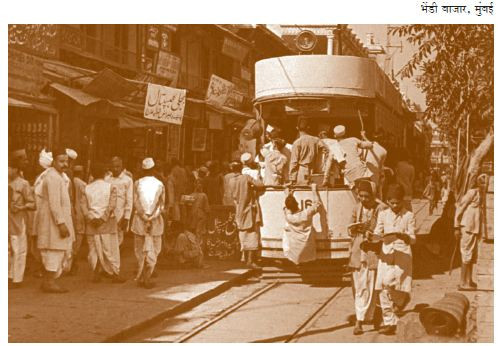

One morning in 1946, I walked along the tracks of tram 16 from Grant Road to Paydhonie in Mumbai. I was all of 14, and had just fled my home in coastal Konkan. I was on my way from one relative's place in the suburbs to another's at Bhendi Bazar in downtown Mumbai.

I was totally oblivious of the fact that Hindu-Muslim riots had broken out there, a day before. I was more preoccupied with the guilt of having run away from home. Lost in thought, I ambled along the track. Very few people could be seen on the streets. Trams weren't running either, I think. Police patrol vans drove past occasionally, and there was police presence on the street.

The Golpitha roundabout was littered with shards of broken glass bottles. I walked up a little further and reached Gol Deul (round temple). I stopped in my tracks when I came across a mob of few thousand Hindus, facing Bhendi bazaar. Not too far from there was an equally large mob of angry Muslims. Life stood still in the stretch of the road that separated the two mobs. It looked desolate and abandoned.

The real sense of the term communal riots dawned upon me at that moment. A chill ran down my spine as I realized that I am perhaps the lone Muslim in a mob of Hindus. Dumbstruck, I hung around there for a bit. And then, out of nowhere, several vans of police reinforcements arrived on the scene, and started dispersing the mob. I did an about turn, and walked straight back to Grant Road.

It's been nearly 19 years since that incident, and the patch of no man's land near Gol Deul that separated the two mobs, has faded away. There have been no Hindu-Muslim riots in Mumbai in the past 18 years. A tram conductor once told me that there was a time when Hindu women, on their way from Grant Road to Crawford market, never boarded tram 16 that passed through Muslim quarters. They would take tram 10 to J.J. hospital, and then change trams instead. I can now see them freely roam the streets Bhendi bazaar.

The Muslim quarters of Mumbai too are no long exclusively Muslim. The houses of many of those who left for Pakistan have been handed over to refugees who came from Pakistan. Along Mohammed Ali Road, between Mandvi post office and Crawford market, you can now see some buildings occupied by Sindhi Hindu refugees. That does not mean the area has lost its distinct Muslim character. The Sindhi Hindu does not feel out of place there. A Sindhi Hindu resident of the area did not know that I am Muslim. When he found out, he said emotionally, "Oh. Turns out you are one of us." It is perhaps this inclusiveness that has preserved the character of the place.

Bhendi bazaar was undeniably the epicentre of Muslim political activity. It was this neighborhood that conferred the leadership of the community upon Jinnah. It was this neighborhood that originally fostered and spread the movement for the creation of Pakistan. Wealthy Muslim traders from the Khoja and Memon communities provided the money muscle for the movement. It was here that the Habib Bank was born, and went on to become Pakistan's national bank. It was at the Kesarbaug grounds in Bhendi Bazaar where Muslims first heard Jinnah's call for an independent Pakistan: And slogans of "Pakistan Zindabad" rented the air, it is said. Bhendi bazar in some ways was a capital in exile for the proposed new nation.

A veteran Muslim politician from the national freedom struggle, once narrated to me an incident from one such Jinnah rally in Kesarbaug. Jinnah rallies followed a set pattern. The stage used to be flanked by the Chand Tara (Crescent moon and star) flags of the Muslim League. Volunteers of the Muslim National Guard would be in readiness to provide standing applause. The media contingent would be seated up front, right next to the dais. This was followed by rows for the invitees and commoners respectively.

On that particular occasion the organisers made a mistake. The invitees were seated in front of the Press. Nobody realized this mistake at first. When Jinnah walked up the dais, and glanced at the audience, he was unable to spot familiar press faces. Enraged, he said aloud to his associate on the dais, "Mr. Chundrigar, where is the Press? Do you think I am here to address these stupid Muslims: I want the Press."

Mr. Chundrigar somehow managed to pacify Jinnah. After a while Jinnah too calmed down, and stood up to "address" the rally. Cries of "Qaid-e-Azam Jinnah Zindabad' filled the air. The first sentence he uttered, was, "These Congressmen think Muslims are stupid."

Some of those present on the dais had heard Mr. Jinnah's earlier outburst. Members of the audience had not heard the same. Not that it would have mattered. The crowd would have patiently heard Jinnah even if he had cried out, "All you Muslims are stupid". In fact, the remark may have been greeted with more cries of “Qaid-e-Azam Jinnah Zindabad."

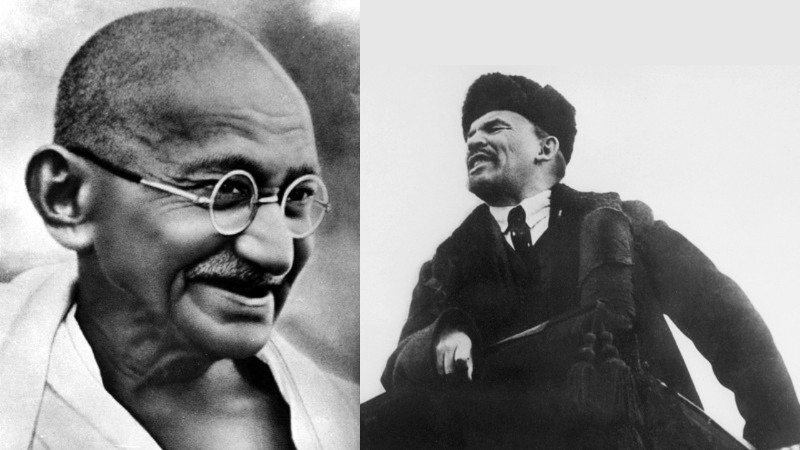

How did this crazy and extreme devotion (to him) take root among Muslims, is beyond me. And beyond a point, it's futile to think about it. It's just like those Germans who still hail Hitler, knowing fully well that Hitler led Germany to her doom. Similarly, in the throes of frustration and depression that followed the creation of Pakistan, the Muslim society still harbors some love for Jinnah.

Therefore, when an outsider to (Jinnah's) politics like me, walks the streets of Bhendi Bazaar, the voice of Jinnah's Kesar Baug rallies still rings in his ears: Just like the American judge in the movie on the Nuremberg trials. And I do see some disappointment writ on Muslim faces here, for having missed Jinnah's voice, guidance, and unequivocal leadership.

Nevertheless, the tide of time is changing things in Bhendi Bazaar too. Waves of industrialization are disintegrating the monolith of Muslim society and dividing it into subclasses such as industrial labourers, middle-class educated office goers, wealthy traders, and the noveau Mumbai cosmopolitan. Those Muslims who have imbibed western education, choose to live in the genteel neighborhoods from Colaba to Malabar Hill. They use forks and knives at their dinner table. And they mostly converse with each other in English. Their children most attend convent-run schools. They are convinced that they have truly turned cosmopolitan, and look down at Muslim neighborhoods.

The Muslim laborer puts up where he can but sticks more steadfastly to his customs and traditions.

It's the bourgeois Muslim who feels most stifled. He lives in a Muslim neighborhood (He would find it difficult to find a place in any other). He genuinely wants his children to benefit from modern education and society. He laments the fact that we (the Muslims) do not understand the importance of modern education. He therefore sometimes strives to keep himself and his children aloof from the community.

The rest of the Muslim society is not alarmed by this middle- class Muslim. For he joins their Moharram tazia procession and frantically flaunts, Ghaus's panja* (footnote needed). On festive occasions, he dabs a fresh coat of paint, however cheap, on his house walls; and borrows money if required to get new clothes for the family. On the day of Ramzan Eid, the middle-class Muslim throws a colorful kerchief around his neck, and tucks a swab of ittar (traditional perfume) in his earlobe. He goes around greeting friends and relatives with his hearty Eid Mubarak hugs. He always puts his religious customs and traditions ahead of his civic concerns.

You, however, cannot compare Muslim neighborhoods like Bhendi Bazaar and Madanpura with say the African American ghettos of New York city, such as Harlem. Those ghettos are a curse to American community living. The African American struts around in the streets of Harlem. He exudes the feeling that his writ shall run large in that neighborhood. But the same African American gets cowed down by a deep set complex, when he visits a white neighborhood. The Muslim in contrast struts around everywhere but walks with more spring in his step on the streets of Bhendi bazaar, because his religious zeal is the backbone of his personality. It would be worthwhile to trace the origins of American Black Islamic movement to this extreme religious zeal.

In Mumbai, the Muslim is no longer restricted to certain localities. Muslim neighourhoods now dot burgeoning suburbs in every corner of Mumbai. Muslims make up at least half of the squalid shanty towns (local word 'zhopadpatti's) of Mumbai. These slums mirror the economic distress of the Muslim masses. There was a time when Muslims from the coastal Konkan region formed a majority among Mumbai Muslims. The Dongri area in Bhendi Bazaar and Naupada in Bandra still bear some signs of Konkan Muslims. But when hordes of settlers from other parts of India thronged Mumbai, large numbers of Muslims from other states also came. Today, the Mumbai Muslim society is teeming with Muslims from Bihar, Uttar Pradesh and Gujarat states, and the Malabar region. Muslims from Konkan and other parts of Maharashtra are seldom seen. Those Maharashtrian Muslims that have survived, have lost their unique identity. They have given up their mother tongue Marathi, and imbibed Urdu instead.

They have adopted the ways of the North Indian Muslims - be it ideas, traditions and even clothing.

If you meet Maharashtrian Muslims, they may actually avoid speaking in Marathi. If someone like me insists on Marathi, they silence me with the refrain, "Brother, when two Muslims meet, they speak Urdu." The Gujarati Muslim also addresses them in Gujarati and finds nothing amiss that Gujarati is mainly spoken in his own household.

The regional and subcommunity divides, however, somehow persist in the Mumbai Muslim society. The Khojas, Memons, and Bohra Muslims have built separate community masjids. (Therefore, the Bohras do not pray at non-Bohra mosques and conversely, non-Bohra Muslims never offer prayers at Bohra mosques.)

The regional and subcommunity divides, however, somehow persist in the Mumbai Muslim society. The Khojas, Memons, and Bohra Muslims have built separate community masjids. (Therefore, the Bohras do not pray at non-Bohra mosques and conversely, non-Bohra Muslims never offer prayers at Bohra mosques.)

As a token of erstwhile preponderance of Konkan Muslims, the management of the Jumma Masjid near Crawford market and the Mahim Masjid, is still with Konkan Muslims. Special Eid prayer congregations always face these two masjids, because prayers there are offered as per ancient (Shaafi and Hanafi) traditions.

The Khojas, Memons, and Bohras have also made an indelible mark on the Mumbai's business world. The Khojas have made a place for themselves in the grain markets of Dana Bunder, while the Bohras dominate the trade in glass, paper, and other materials. The Sindhis who migrated following Partition of India have established themselves in practically all businesses. This has had an impact on the community. As Mumbai turns into a hub of large, capital-intensive industries, the Muslim traders complain that they are falling behind in business.

Among them, the Bohra community not only has different customs and traditions, it flaunts its Bohra identity. The modified hijab garment worn by Bohra women (the rida) is a glowing example of distinct Bohra identity.

The system of forming queues took root in Mumbai during World War II. It is a common practice to form queues to board the city bus. In Muslim quarters, they do not form queues. Which is not surprising since they seem to care little for their civic duties. It is unlikely therefore that you'll find any queues at the bus stops between J.J. hospital and Crawford market (now called Mahatma Phule Mandai). People hang out in small groups at these bus stops and throng the bus as it arrives. In the free for all that follows, burqa-clad Muslim women seem to participate with equal aggression. Any Muslim bus conductor allotted to a depot in that neighborhood soon gets fed up of managing this melee all day. He is aware that there are invariably pickpockets at these bus stops. They will make off with anything they can lay their hands onto. And if any alert citizen raises alarm, the pickpockets are quick to draw their deadly knives and place them at people's throats.

The lethal Rampuri Chaku (knife) is an import by Muslim migrants from Rampur in Uttar Pradesh (UP), to the Madanpura neighborhood in Mumbai.

From 1928 to 1930, Pathan goons ran loose across Mumbai. They doubled up as money lenders and goons. Rival gangs deployed the Rampuri chaku so effectively against them that the Pathans were on the run. In fact, the Rampuri gangs replaced the Pathans in the underworld, and the Pathans turned to full time money lending instead. The influence of Rampuri gangs waned but the Rampuri chaku became the weapon of choice of the Mumbai underworld. Madanpura became a hotspot for goons and other nefarious elements. Criminals externed by law, could be seen freely roaming the streets of Madanpura. As the red light district was not too far from Madanpura, it became a beehive for pimps and drug dealers. While the scale of crime in that area has reduced, during an evening stroll, you can spot a few people openly smoking grass in a traditional chillum pipe.

Madanpura is mainly a colony of migrant UP Muslims in Mumbai. The neighborhood is changing. It has Muslims from dif ferent parts of UP. Very few of them are educated and they speak chaste Urdu: Others speak their Hindi dialects such as Purabi, Uttari, Awadhi, and Magadhi. They read the Inquilab or Urdu Times. They work in nearby industrial units or cloth mills or at the cloth market. Trade unionism naturally is seen in this area with the Unions reflecting nothing but the idealogy of the parent political party. If there is a march to demand regional language status for Urdu on par with Marathi, this area provides the most participants. When hawkers and street vendors stage a march, it usually originates in the Jhoola maidan grounds in Madanpura. The next day, you can sometimes see local residents by the kerb-side, reading up juicy descriptions of the march from the Marathi daily 'Maratha" (or at least getting someone to read it for them).

Madanpura houses various sections of north Indian society. From the cobblers and dhobhi washermen to Ansar weavers that trace their links Kabir. But they are very territorial and loathe to rivals, even those from Muslim community, settling in the neighborhood. Madanpura is not too far from Bhendi Bazar, but it is yet to come to terms with Bhendi Bazar. The difference is evident during a quick walk from Jhoola maidan to Kesar Baug. Soon you'll notice that newspaper vendors in Bhendi Bazar have Paki stani dailies such as Dawn and Anjaam on sale.

Gumasta is one lawless neighborhood in these parts. Hair cutting saloons, restaurants and other shops in this area remain open very late into the night. Flashy decor marks these shops. Countless mirrors and flashy fluorescent tubes, light up the night, and loud Hindi film music blares through the ear all day. Irani tea shops, however, are seldom found in this area because the common Muslim will never settle for a basic breakfast of tea, bread, and butter. He needs something more substantial. It is perhaps therefore that Moghlai restaurants run by Chilliya* (footnote needed) dot this area. Shig, a roast beef snack is regularly sold on the streets of Gumasta.

Beef is regularly sold in the restaurants in the area, and vendors can be seen delivering raw beef orders at every doorstep. "Beef is cheaper (than mutton)", one is told. Gangs dealing in il licit cow and buffalo slaughter are active in Bhendi Bazar and Madanpura. It's not as if they are in the trade to offend Hindu sentiments. They do it as naturally as a Christian gangster sets up hooch business (despite the taboo). The beef trade has a network from Borivali and Ghatkopar to Colaba. They carry out their business coldly. Their modus operandi is remarkable. They are on the lookout for stray cattle and can reduce a cow or buffalo to mincemeat within 10 minutes. Their skills of cutting up cattle, separating the hide and fat from the meat, and disposing off the waste, would be a surgeon's envy. They usually get around in a station wagon or Jeep, in which they load the meat, and disappear from the scene within minutes.

The Pathans, who had disappeared from the Mumbai scene after the creation of Pakistan, emerged again out of nowhere. Their borrowers jokingly refer to their money lending business as the Pathan Bank. Not all of these Pathans speak Pushtu. Many of them hail from Afghanistan. They have made their base in the suburb of Sewree. The Pathans strictly adhere to their religious duties, such as offering Namazs and observing Rozas or day-long fasts during the month of Ramzan. They subsist on the un-Islamic practice of charging interest on loans, nevertheless. I estimate their number to be around five thousand, half of whom should be illegal residents in India.

Just as the Muslim populace is now scattered across sprawling city, the Muslim society is losing its homogeneity in social, political and religious matters.

For example, there was seldom any debate within the Muslim community over the Zatka method of animal slaughter. Dissenting voices can now be heard on the matter. Muslims intensely debate issues like polygamy and the burqa within the community. Supporters and detractors of Pakistan engage in fierce political debates. Morever, they analyse these debates from the Islamic religious point of view. A progressive section of the Dawoodi Bohra community, for example, has formed an association, and challenged the high priests of the community.

Amid these conflicting voices, leaders such as Haris* and Faqi* (these names and spellings need to be verified), who devoted themselves to the freedom struggle, appear like tiny islands in an ocean. They barely exist on the fringes of Muslim social life. Perhaps the community has not forgiven them for "betraying" the movement for revival of Islam.

I often bump into Shaukatullah - an old freedom fighter from UP. He belongs to the tradition of nationalist leaders. He is a tired man now, and often needs to take short breaks as he walks. He gave up meat when he joined Gandhi's Quit India movement in 1942. In the heat of the freedom struggle, he forgot to get married. The community nearly ostracized him (for siding with Gandhi). Today, he appears like someone gone adrift in a giant current (of time).

Despite his sorry state, I have never seen him regret the life he led. I still see that spark of indefatigable devotion (to India's freedom) in his eye. Distributing copies of Gandhiji's mouthpiece 'Harijan' was his favorite activity. He was devastated when the Harijan folded up, but he soon calmed down. Arguing against communal Muslims, he slams his fists on the table and screams, "These idiots haven't changed. They still haven't changed!" While bitter religious zeal was at the heart of the community's extreme stand (during creation of Pakistan), those who fought the communalists, like Shaukatullah, perhaps also drew their extreme zeal from religion.

Amid these conflicting voices, life in Muslim quarters of Bhendi Bazar goes on smoothly, unquestioned... pretending to ignore the signs of change. This stereotypical image of Bhendi bazaar represents a lacuna in our nationalism... a bad omen that speaks of a chink in the national armor.

Nehru once spoke of reestablishing dialog with the Muslim community. Like many of Nehru's declarations, this too faded into thin air: The Muslim community remained insular. The isolation of Muslims who now live in every corner of the city is coming to a close. Only when the insularity is completely destroyed, and Muslims join the mainstream Indian life, will the dream of national unity be realized. Until such time, Bhendi Bazaar will continue to remind us of the cracks in our nationalism.

(Original Marathi Article was published by Kirloskar magazine in July 1965, as part of a Mumbai city special.

Reprinted in Sadhana Weekly's 68th Anniversary Special Edition dedicated to Hamid Dalwai, dated 15th August 2015.)

Translated by Sanjay Pendse

Read the original article here: मुंबईकर मुसलमान

Tags: hamid dalwai muslim muslim league jinnah muslim localities hindu-muslim riots bhendibazar Load More Tags

Add Comment