The communal super-egos and superiority complexes associated with sub-castes have not entirely disappeared even among the Brahmin and similar upper-caste communities, despite reaching the peaks of economic and educational privileges. Therefore, although the Creamy Layer issue was not directly pled before the Supreme Court this time, the recommendation is not inappropriate.

On August 1, 2024, the Supreme Court of India delivered an important verdict and made a recommendation along with it. The verdict and the recommendation together have the potential to give a decisive turn to India's reservation policy. However, it is evident that the political will in this country is not mature enough to take full advantage of this opportunity, as many of our socio-political leaders are reluctant to think holistically. As a result, our society has to undertake a long and laborious journey before a definite public opinion can be shaped in this regard. Ultimately this harms the nation. The same situation is unfolding now.

Demands are emerging to change the verdict. Various forms of protests have been ongoing for a while now. The four large states - Rajasthan, Madhya Pradesh, Uttar Pradesh, and Bihar - are leading the charge in this regard. The Samajwadi Party is the largest opposition party in Uttar Pradesh, the largest state in the country. They have shown vigorous opposition to the verdict. Rashtriya Janata Dal in Bihar (the third most populated state in India) has also taken a strong opposition to it. Other political parties are expressing themselves in an indecisive manner. Obviously, they are cautious of the impact on their party's voter base and the potential electoral consequences. Among scholars and intellectuals, some oppose the decision, others cautiously welcome it, while the rest remain conveniently silent.

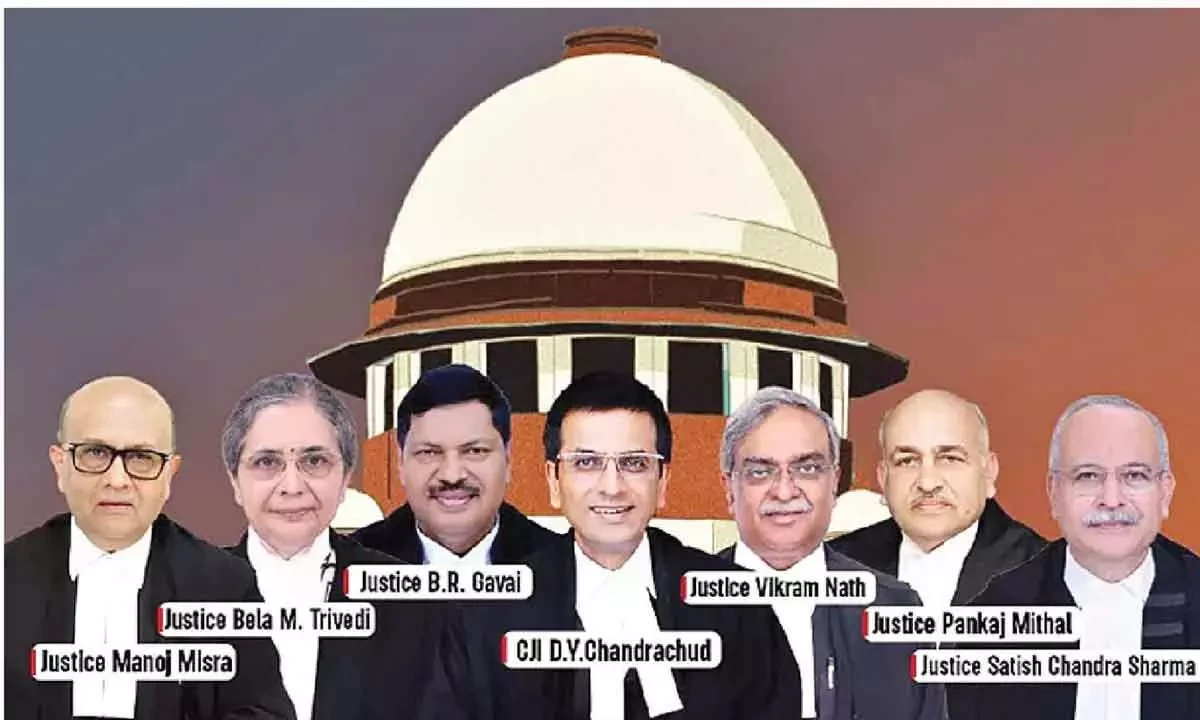

What does this Supreme Court verdict mandate? It grants approval for the sub-categorization within the reservation for Scheduled Castes (SC) and Scheduled Tribes (ST) in education and government jobs. Additionally, the court has recommended considering the application of the Creamy Layer concept to SCs and STs. This ruling is in contrast to the Supreme Court's 2004 verdict. In 2004, a five-judge bench had ruled that sub-categorization within SCs and STs, similar to that within OBCs, could not be done. However, the current seven-judge bench led by Chief Justice Dhananjay Chandrachud has overturned that decision, stating that there is no objection to such sub-categorization.

Within the constitutional framework of India, SCs are granted 15% reservation and 7.5% reservation is granted to STs. Further sub-categorization within these groups can now be carried out. State governments will have the authority to implement it. This has removed a significant hurdle in the path of implementation. As a result, sub-categories such as backward, more backward, and less backward can now be created, with SCs possibly being divided into three to five sub-groups and STs into two to three sub-groups. It would aptly reflect the current socio-economic conditions in the country.

As of today, the total number of Scheduled Caste (SC) communities across the 28 states and Union Territories in the country stands at 1,108 (as per the lists in the Indian Constitution). In smaller states, this number ranges between 5 and 15, in medium-sized states between 30 and 50, and in larger states between 60 and 101. Karnataka has the highest number of SC communities, with 101, followed by Odisha with 93 and Maharashtra has 60.

For the Scheduled Tribes (ST) category, there are a total of 744 communities spread across 22 states and Union Territories (as per the lists in the Indian Constitution). In smaller states, the number ranges between 5 and 10, in medium-sized states between 15 and 25, and in larger states between 30 and 60. Karnataka and Odisha lead in this category as well.

Given this reality, any person with a basic awareness of political and social dynamics would approve of the sub-categorization. Over the past 75 years, the SC and ST categories have been treated as two homogeneous groups, with blanket reservation opportunities provided to all communities within them. As a result, some communities within these groups have had easier access to more opportunities in education and employment, thereby achieving greater representation. However, many communities within these categories have remained significantly underprivileged, leading to fewer educational and employment opportunities for their youth, and consequently, minimal representation. Among the more marginalized communities within the SC and ST categories, there is certainly a feeling of despair at being neglected. However, this discontent has not yet been voiced out enough, as these communities lack the collective strength of organization and the capacity to raise their voices or to engage in struggle movements.

On the contrary, those who oppose sub-categorization are ready to fight collectively. It implies that they have become somewhat more empowered than the other sub-groups. Their argument is that the verdict is an attempt to curtail the progress of those within the SC and ST communities who are starting to advance, aspiring for higher-ranking professional positions, and trying to compete on a larger scale. They argue that just as they begin to make some progress, this is an attempt to hinder them. There is indeed some validity to their argument. However, a counter-argument could also be made with the same logic: is it an attempt by the slightly more empowered groups to deny progress to the more marginalized communities within the SC and ST categories? And if the right time for sub-categorization has not yet arrived, how do we bring the most backward communities up the social ladder? If seventy-five years have not been enough, how many more years will it take before sub-categorization is acceptable, or will it never be?

Of course, one could argue that even today, the numbers of SC and ST individuals in high-ranking posts such as secretaries, diplomats are minimal. Social equality is still a distant dream. But then the question arises: given our historical and current context, social equality may not be achieved even after five hundred years! Moreover, in this entire discussion, the focus has shifted away from the original purpose and goal of the reservation policy. The primary objective is to ensure adequate representation of the backward communities in education and government jobs. Here, ‘adequate’ does not mean proportional to the population or until social equality is achieved. It means until these communities are capable of fairly competing with others.

The current Supreme Court ruling pertains only to the issue of sub-categorization within the SC and ST groups. However, four of the seven judges on the bench went beyond the purview and recommended that the government should also consider introducing the provision for a Creamy Layer within the SC and ST categories similar to the OBC category. This suggestion has sparked the same kind of conflict as before, ranging from "Why has the court even expressed this opinion?" to "This is part of an upper-caste conspiracy."

The current Supreme Court ruling pertains only to the issue of sub-categorization within the SC and ST groups. However, four of the seven judges on the bench went beyond the purview and recommended that the government should also consider introducing the provision for a Creamy Layer within the SC and ST categories similar to the OBC category. This suggestion has sparked the same kind of conflict as before, ranging from "Why has the court even expressed this opinion?" to "This is part of an upper-caste conspiracy."

In reality, the judges have applied the same social criteria and logical reasoning in both the cases - while delivering the verdict about the sub-categorization within the SC and ST categories, as well as while making the recommendation about introducing Creamy Layer. Their argument is both relevant and justified. They question, why should the children of SC and ST individuals who are IAS or IPS officers still benefit from reservations? Most people agree that economic and educational backwardness has been alleviated in such cases, but some argue that social backwardness still prevails. However, it may take several more centuries to eradicate the remnants of social backwardness. The communal super-egos and superiority complexes associated with sub-castes have not entirely disappeared even among the Brahmin and similar upper-caste communities, despite reaching the peaks of economic and educational privileges. Therefore, although the Creamy Layer issue was not directly pled before the Supreme Court this time, the recommendation is not inappropriate. In the future, a plea will inevitably be brought before the court to implement the Creamy Layer within the SC and ST categories, and when that time comes, the court will likely have to issue a ruling in line with the recommendation made by the four judges. This is indeed the direction that rationality points toward.

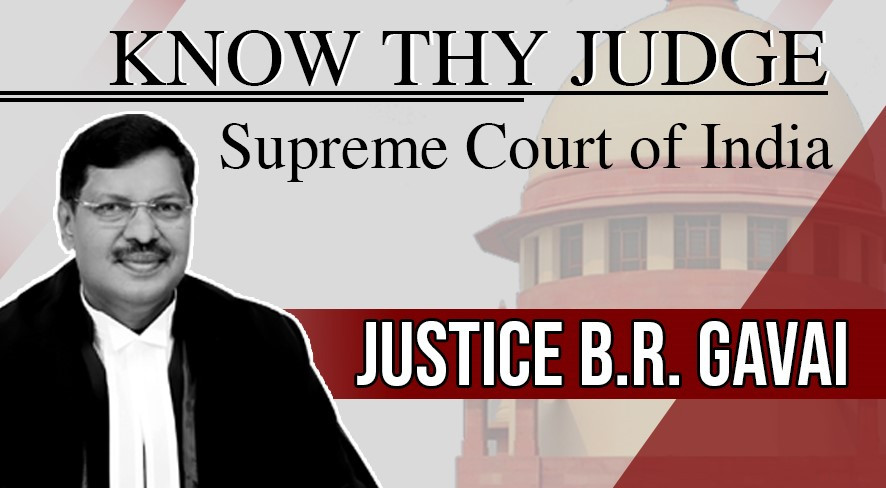

Among the four judges who made the recommendation regarding the Creamy Layer, Justice Bhushan Gavai stands out. He is set to become the Chief Justice of India within the next year, provided the seniority order is respected. Justice Gavai hails from Amravati district in Maharashtra. He began his legal career at the Nagpur High Court and has served as a judge in both the High Court and the Supreme Court for the past twenty years, earning significant reputation. He also carries a strong intellectual legacy and social consciousness inherited from his father, R.S. Gavai. R.S. Gavai was a close associate of Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar in his youth, later served as the president of the Republican Party of India, was a member of the Maharashtra Legislative Council (MLC) for thirty years. He helmed important positions in the MLC such as Leader of the Opposition and Speaker. He was an MP in both the Rajya Sabha and the Lok Sabha, and towards the end of his political career he became the Governor of Kerala and Bihar. His stance was consistently in favor of social justice, marked by a balanced and comprehensive approach.

Therefore, when Justice Bhushan Gavai speaks on the Creamy Layer issue -despite the fact that no case on this matter is currently before the court - his intent should be understood in light of this legacy. Instead of viewing him with suspicion, we should consider his significant intellectual heritage and recognize that his initiative is not only natural but it should actually be welcomed and proudly celebrated.

Therefore, when Justice Bhushan Gavai speaks on the Creamy Layer issue -despite the fact that no case on this matter is currently before the court - his intent should be understood in light of this legacy. Instead of viewing him with suspicion, we should consider his significant intellectual heritage and recognize that his initiative is not only natural but it should actually be welcomed and proudly celebrated.

That said, just because the Supreme Court has issued its recent ruling, it does not mean that all states will immediately begin implementing sub-categorization. Similarly, even though Justice Bhushan Gavai and the other three judges expressed their opinion on applying the Creamy Layer principle to SC and ST categories, it does not mean that a case will be filed or a decision will be made right away. After the recent ruling, around 100 SC and ST members of Parliament from various parties met with the Prime Minister, expressing their concerns - either out of fear for their vested interests or genuine conviction. The Prime Minister reassured them. All that is well and good, still, while the Supreme Court has removed the obstacle to sub-categorization after an arduous twenty-year process, it may take another ten to twenty years for the issue of Creamy Layer to be discussed in the court. By then, the centenary of India’s independence will be upon us. If our mindset still remains resistant to sub-categorization and the Creamy Layer by that time, it will serve as evidence of the inaction of our social and political leaders.

In reality, the concept of the Creamy Layer within the OBCs exists only on paper, and its implementation is quite inconsistent, with numerous loopholes. Therefore, the first priority should be to tighten the criteria for determining the Creamy Layer within the OBCs. For example, if the benefit has been availed by one or two generations, it should not be available to the third generation; or if it has been granted in education, it should not be granted in employment. Additionally, castes that have achieved adequate representation should be removed from the category. For instance, OBC castes that have gained sufficient representation should be excluded from reservation benefits. In the future, a similar situation may arise for SCs and STs, and we should aim for that to happen sooner rather than later.

However, our current data system is quite inadequate to accomplish this. Hence the implementation will be very challenging. The caste-based census has been avoided until now due to concerns that it could harm national unity, and that fear still persists. However, the so-called upper castes, considered privileged and dominant, are now demanding reservations. They are scared that their already diminishing share in the administration and in government jobs will decrease further. Compared to such a reservation scenario, damage caused by conducting a caste-based census might be relatively minor.

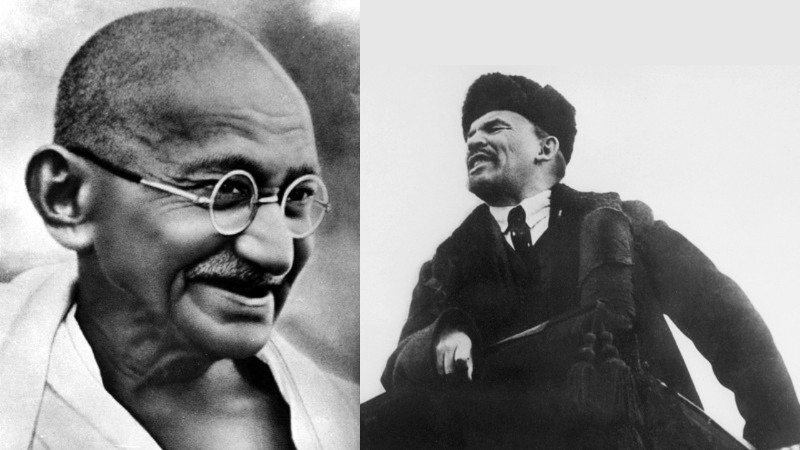

Against this backdrop, it's pertinent to recall Mahatma Gandhi, who focused on the upliftment of the marginalized groups, and Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar, who fought to free the backward classes from the shackles of the caste system. We should consider their struggles, teachings, and positions collectively. While they had significant differences on many issues, if they were alive today, they would likely have agreed on the recent Supreme Court verdict, and they would have welcomed it. They would have also endorsed the recommendation made by Justice Bhushan Gavai and the other three justices, and urged not to delay its implementation!

- Editor

kartavyasadhana@gmail.com

Translated by Rucha Mulay

Tags: sc-st reservation policy constitution gandhi ambedkar quota within quota Load More Tags

Add Comment