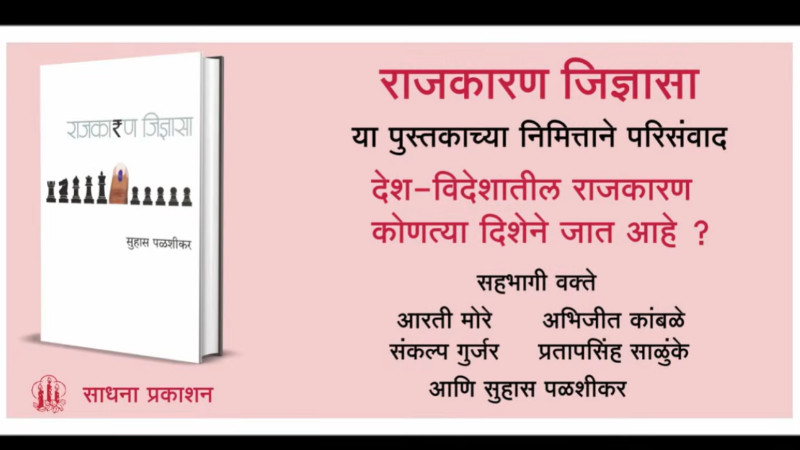

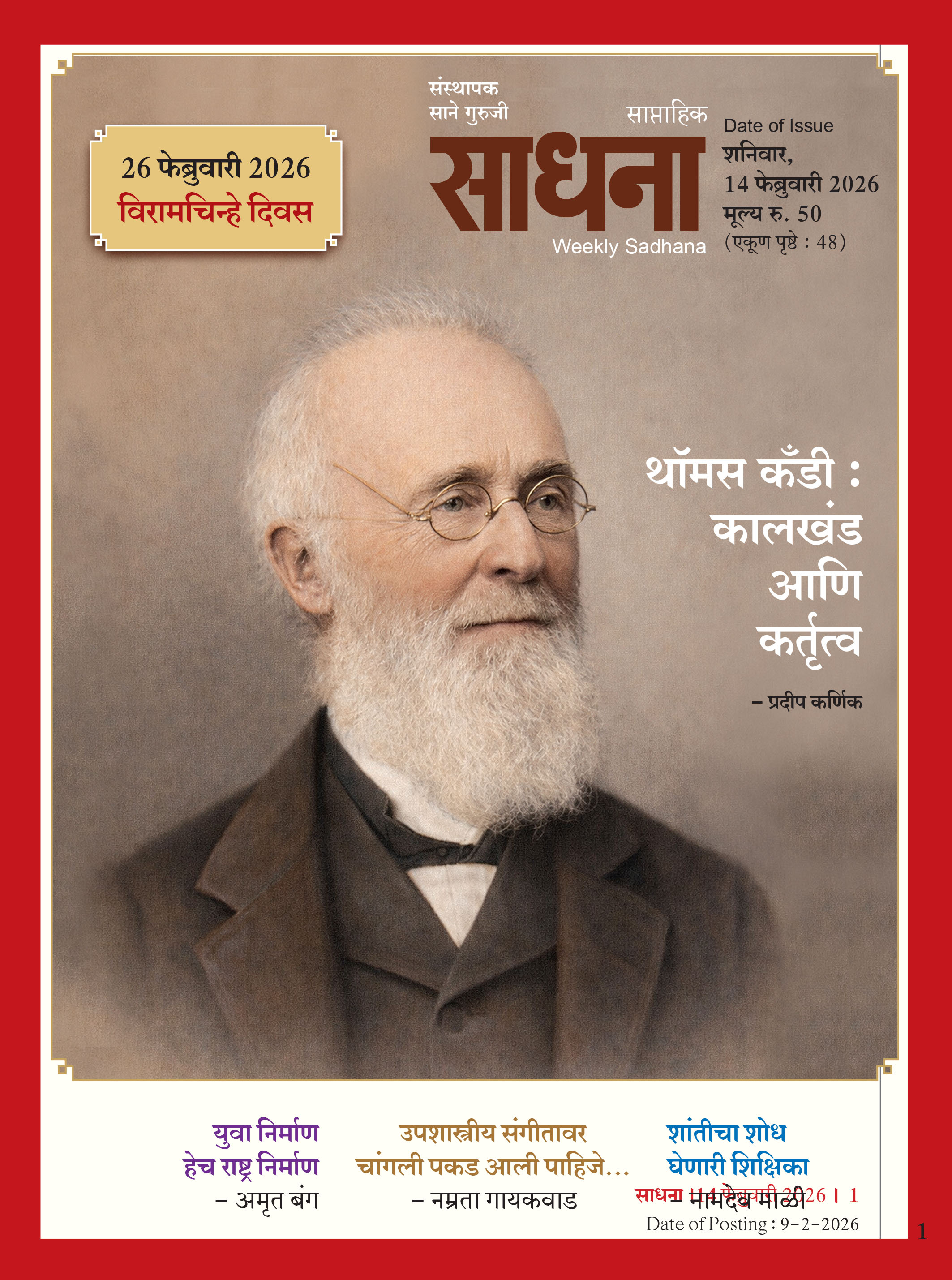

On 15th August 2022 as India celebrated completion of 75 years of Independence, Sadhana Saptahik (Weekly Sadhana) entered the 75th year of existence. The special edition marking the milestone was thematically titled as "कालचे स्वातंत्र्य आमच्या दारात आलेच नाही… The Freedom You Got Yesterday Has Never Reached Our Doorstep." The special issue featured interviews with four prominent national figures—Kishorchandra Deo, Balkrishna Renke, Kancha Ilaiah Shepherd, and Noor Zaheer—who delve into how much beneficial national independence has truly been for the marginalized communities over the past 75 years.

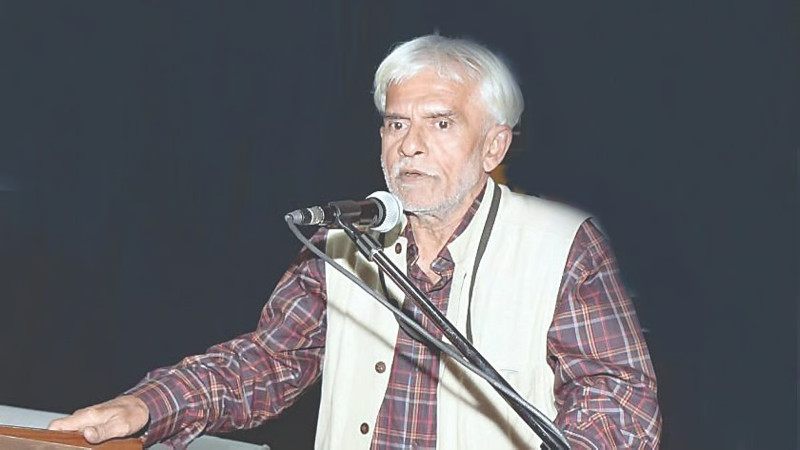

The In-depth Interview of Balkrishna Sidram Renke, the former Chairperson of the National Commission for Denotified, Nomadic & Semi-Nomadic Tribes, gives insights into the plight of the communities, their fight for justice and the requirement of a wholesome plan for development. To mark the Independence Day and Weekly Sadhana's Anniversary this year, we urge you to revisit this interveiw in English.

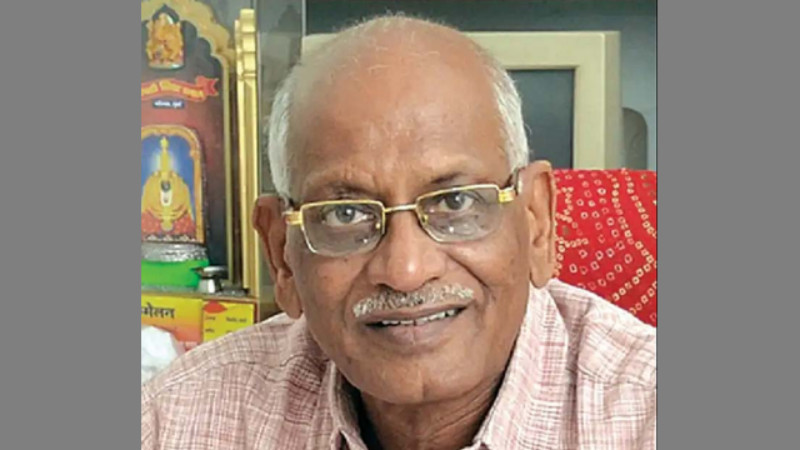

Balkrishna Sidram Renke, the former Chairperson of the National Commission for Denotified, Nomadic & Semi-Nomadic Tribes, is currently the president of 'Lokdhara', a national organization of nomadic people. He took up the government job after completing his education under very difficult conditions. Along with his job, he also conducted the work of awareness and organization amongst the nomadic communities. However, in 1973, in his youth, he voluntarily resigned from the government job and devoted himself to the movement of nomads. From then till today, he continues to champion the struggle for the issues of the nomadic communities, looking at their causes and possible solutions. In order to reduce the injustice and oppression of this abandoned nomadic community, it is necessary to ensure that they get firewood, fodder, food, shelter and minimum income, it is necessary that they have access to resorces. This is the role within which, he, as an experimental farmer has been working. His work in the field of agriculture was recognised and he was honoured with the awards 'Sculptor of Organic Farming' and 'Krishiratna' by the Government of Maharashtra. We are presently celebrating the Amrut Mahotsav, marking seventy-five years of our country’s freedom. Moreover, the Sadhana Weekly, dedicated to social, ideological enlightenment for social transformation, has also entered its 75th year. On this occasion, let’s understand from Renke anna, who has been working in the same social sector for a long time, about how much freedom has trickled down to the development-deprived elements like nomadic tribes scattered all over the country, how much and in what way are they involved in the process of self-government.

Question - Renke sir, please tell us a little about your childhood and youth.

Answer - I was born in the pre-independence era to poor and illiterate parents in the Gondhali tribe, who are traditionally priests. My native place is Tadola, in Gulbarga district, located in the border area between Maharashtra and Karnataka. I’m not sure exactly how old I was at the time of independence in 1947, but as per the date of birth recorded by the teacher in school (5-6-1939) I was nine years old then. My parents did not understand how dates were calculated. Their units for measuring time were festivals, seasons, epidemics and so on. However, they were of the opinion that the teacher’s school record was approximately correct, give or take a year to 1.5 years.

I remember the Prabhat-Feris (community morning walks in protest of British Government) in the village in the year before independence, the slogans which called out names of various patriots. I met my elder brother Madhav for the first time at the age of nine, on the occasion of one such Prabhatferi. All of us at home used to call him 'Dada'. Due to the efforts of Devi Singh Chavan, a Gandhian leader from this area who worked towards spreading education, Dada stayed at a boarding school away from home.

Dada had hoisted the tricolour on the neem tree in our front yard in the pre-independence period itself. I could not understand much, but I was attracted to the tricolour flag, to the Prabhatferi, to the slogans. It was something of novelty. Although I did not speak Hindi, the song 'Vijayi Vishwa Tiranga Pyaara, Zanda Uncha Rahe Hamara' I knew by heart. After completing the Prabhat-Feri, Dada would go back to the boarding school. It was during this time that a school was set up in our village under a tamarind tree. I don't really know why or how, but my father wanted his sons to be educated. He was adamant that his children go to school. There was no interest in education among our relatives and friends. But our father forced me to go to school, sometimes with love and sometimes with fear. My basic education of alphabets and blends was done in the school under the tree.

After independence, a primary school was set up in the neighbouring village of Kesar Jawalga, five kilometres away. Father forced me to go there. The routine of walking to school every morning and walking home in the evening continued for two years. In two years, I passed my fourth grade. By that time, Dada passed his matriculation and got a job as a primary teacher. He was appointed at a one-teacher school in Surdi village of Osmanabad taluka. Dada took me with him for further education. Because the school had only one teacher and was a primary school, for fifth grade I was placed in Lohakare Guruji's school and hostel at Gaudgaon in Barshi taluka. In this manner, sometimes with Dada, sometimes alone, I managed my education up to matric through eight schools in Maharashtra.

I passed Inter Science in 1960 from Dayanand College, Solapur. Until then, the government had adopted the policy of educational fee waiver for the economically weak. We never received the caste certificate because we did not have the necessary documents to be submitted as proof. Finally we managed to get a financial income certificate with much effort. But the Maharashtra government refused the concession as it was from Karnataka. We went to Bijapur in Karnataka to get the concession. As I was a Marathi man living in Maharashtra for the last twelve years and also educated in Maharashtra, Karnataka rejected the concession.

In the end, I had to work hard, earn and learn. After studying in eight schools in Maharashtra and three colleges in two states, I finally graduated in science from Dharwad University. But this journey was laborious. I had to face insults, contempt, neglect, hunger, pain. I was able to overcome these difficulties only because I met some good people, some good friends.

Question - Anna, how did you get drawn to social work? How did your life take this turn?

Answer - While going through this whole experience, many thoughts, many questions arose in my mind. Forty-fifty students were studying in the school which was set up under a tamarind tree. Fifteen-twenty children from the village would walk and study with me in the school in Kesar Jawalga. My mind was always busy trying to find the reasons why none of them, except me, passed even matriculation, leave alone graduation. If this was the story of the children in a stable society in the village, what must be happening to the young men and women of the unstable nomadic tribes? This thought always haunted me. They had no home in the village, no farm in the forest, no stable and respectable occupation. They were victims of dangerous addictions and superstitions. They were influenced by caste panchayats that insisted on disreputable traditional occupations and customs. Who would convince them that education was important? How would the boys and girls of unstable nomadic tribes learn and live? This thought, these questions always kept me restless. The community of nomadic tribes was more neglected and backward than others, their women doubly backward, millions of their girls were deprived of not only education but also humanity. It was with this anxiety and regret which I had since my years as a student, that I reached Mumbai in 1964 to try my luck. Initially I had to stay on Dadar platform or the pavement for five-six months. But I was not unemployed even for a single day. From being a porter at the station, to daily wage work, I did whatever work I could get. At that time, the daily wage was three rupees, and 60 paise was enough to get a plate of rice. Even if you ate three times a day, I could save money. So the issue of survival did not arise. On August 2, 1965, I got a government job. This provided financial security and ideological stability. I started reading and listening to news in newspapers and on the radio which I bought myself. At the age of 27, I started reading beyond the examination syllabus.

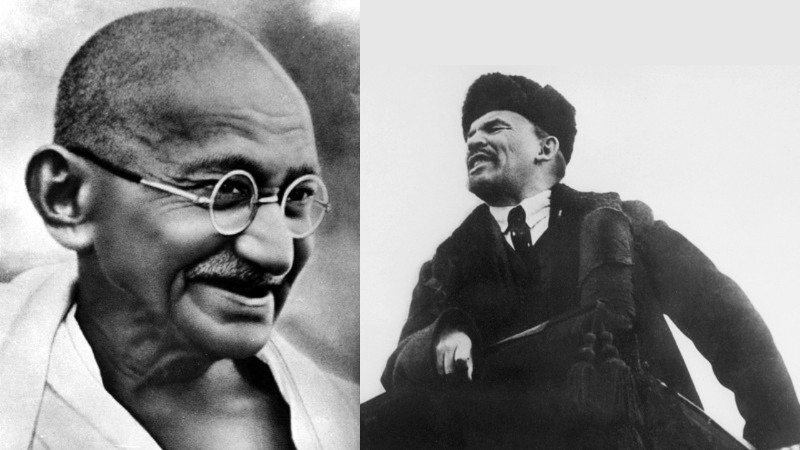

From the literature of Dr. Babasaheb Ambedkar and Mahatma Phule, an inquisitive and analytical aptitude started to develop. I could gradually understand how deeply the mental slavery is ingrained in people's minds. I learned the theory of Karma Vipaka afresh. I had experienced the miserable, decaying life of those who believed that poverty, suffering, misery, disease are all a part of destiny and one has to accept it as it is. There is no example in the history of the world that an established society has gone to the door of the underprivileged with a bundle of awareness and development, just as an uncle lovingly carries a bundle of food for his little niece while going to his sister's house. However, it is clear that nobody got anything without a struggle. That's why Phule - Ambedkar's teachings that focused on how important it is that the marginalized should wake up, become enlightened, understand the cause of the problem or suffering, come together to find solutions, fight for rights, justice and dignity with a sense of responsibility were very touching. They resonated with me.

On one hand, contemplation increased and on the other, the search and study of nomadic settlements in Mumbai area and the government welfare schemes for them started. I read the report of the joint committee of seven MLAs appointed to review the government welfare schemes for the nomads. My uneasiness grew even more when the committee seemed to criticise the implementation of the plans with derogatory remarks like ‘Welfare schemes seem like ornaments in the glass cupboard’, ‘Big Expenditure small benefit’. I wrote a long article on the comparative study of the actual experience and the report and the expected minimum development program for the future. On November 10 and 11, 1971, it was published in the Maharashtra Times in two parts. It was my first journalistic writing. The important and encouraging thing for me was that editor Govindrao Talvalkar wrote his editorial about my article. It further championed my suggestions regarding awareness and organization. I received a lot of respect, love and cooperation from many respectable social workers and a little from the denotified, nomadic tribes. Due to the cooperation of all these sympathizers and companions of the nomads Daulatrao Bhosle, Adv. B.S. Gokaral, Ramdas Deshmukh, Yallappa Vaidu, P.B. Dhotre and others, we were able to hold the first historical statewide conference of all nomadic tribes on January 9, 1972 at Kamgar Krida Maidan, Elphinstone Road, Mumbai. About 25 thousand people attended the conference. In this conference, the foundation of the first state-level comprehensive nomadic organization was laid. The presence of then Chief Minister of the state Vasantrao Naik, Chairman of Legislative Council Balasaheb Bharde, Minister of Social Welfare Baburao Bharaskar proved to be a guiding light and help in further work.

Question - You resigned from the government job for the awareness and organization of the denotified, nomadic people, but who are the denotified, nomadic? I have read and heard that some administrative officers in central government and state government do not know exactly who is denotified or nomadic. Moreover, is it true that the list of nomadic people is not recognized in the central government and the state government, in terms of the role of providing special opportunities for development?

Answer - There is a lot of truth in what you have read or heard. Let us first learn about the community of nomads and denotified tribes. If we start to think back to the very beginning of human evolution, we were all nomads, living by gathering food before the development of agriculture. After the development of the farming system, the collective (Irjik) farming system was followed for some time in the beginning. In this system, the farmers were settled and the skilled workers who cultivated the farm moved from one place to another as needed. In the early days, in the Irjik farming system, after sowing the seeds, the farm was maintained by the farmer and during harvesting, the skilled workers would come back and harvest and they all would share the produce. Later, as the agricultural area increased, so did the cultivators. Farming started with Batai (half share). In this system, consideration, cooperation and meeting each other's needs were prioritized. This role developed further and if anyone faced difficulty in farming, lack of manpower to build a house, other people of the village would collectively help them free of charge as a form of brotherhood.

In some tribes and some villages, this system still survives to some extent. Certainly, it is so in tribal and nomadic communities. As people settled, this practice led to the emergence of nomadic artisans who supplied the settled people with recreational, health, household and agricultural tools, as well as sheltering needs. According to Anthropology and Sociology, as agriculture developed from the way of living by gathering food, animal husbandry also started in the forest. In anthropology, nomadic tribes are recorded primarily as pastoralist nomadic tribes. Not only in our country, but also in many countries, herding nomads, as well as nomadic trading tribes that catered to the needs of settled people were formed.

Indian society had some traditional nomadic communities living off charity or alms given by the people. Even though they were lower in the social hierarchy, they had a status. Sadhus, fakirs, religious priests, fortune-tellers, genealogists, traditional doctors / healers, etc had respect of the settled society, due to the essential services they received from the nomadic tribal professions. There were also nomadic communities who entertained people with the help of animals and birds (monkeys, bears, snakes, owls, parrots etc.) besides displaying cultural arts of storytelling, dancing, singing and music-playing and others. There were also nomads who manufactured household items and implements from iron, clay, wood, bamboo etc. There was a cordial relationship between the settled people of the village and these nomadic tribes. Each other's needs were met by each other. Even from the time of Kautilya, the local kings had preserved the nomadic attribute of these tribes not only as service providers or messengers but also as spies to understand the secrets of the enemy.

If we try to sympathetically understand the history of many forest-dwelling communities like Kanjar, Lodha-Lodhi, Pardhi, Bawari, Mongia, Ahariya, Nishad, Bhill, Gond, Tadvi, etc., we can see that before the arrival of the British, these tribes were living a relatively happy and peaceful life like kings in the forest. They were not at all identified as anti-social communities as they are today. Their way of life for thousands of years was to live in the forest, maintain the balance of growth and utilization of the forest, using the forest as their own life-support, protecting the forest, hunting for livelihood. The forest was their main means of survival. So, the nomads connected with urban life and the nomads belonging to the forest lived happily at that time, following their respective lifestyles.

During the British rule, the British initially put the excuses such as controlling crime and maintaining law and order, and brought the 'Criminal Tribes Act 1871' into existence in Punjab and North-West India. According to this law, the men and women of that particular tribe were considered to be They named select few tribes like Thug-Pendhari as criminals by birth. To establish this, they took the support of the caste system here. As per the caste system, the father's business is carried on by the next generation, and therefore, the children of criminals were believed to be criminals. This time there was no specific opposition from local people or leaders. Because the word thug in practice and in the British dictionary meant forest destroyer, thief, bandit. Looking at the past history of the behaviour of the British in the world, especially the experience of America and Australia, one could point out that they had the shrewdness to impose the incorrect meaning of the word thug on us.

During the British rule, the British initially put the excuses such as controlling crime and maintaining law and order, and brought the 'Criminal Tribes Act 1871' into existence in Punjab and North-West India. According to this law, the men and women of that particular tribe were considered to be They named select few tribes like Thug-Pendhari as criminals by birth. To establish this, they took the support of the caste system here. As per the caste system, the father's business is carried on by the next generation, and therefore, the children of criminals were believed to be criminals. This time there was no specific opposition from local people or leaders. Because the word thug in practice and in the British dictionary meant forest destroyer, thief, bandit. Looking at the past history of the behaviour of the British in the world, especially the experience of America and Australia, one could point out that they had the shrewdness to impose the incorrect meaning of the word thug on us.

The name of the tribe who worshipped Kali Mata as a deity and lived in the forest was Thug. The forest was their home. If there was an attack on their daily life and home itself, it is natural that they would retaliate. They termed this attitude violent, called them destroyers of the forest, thieves, and created atrocity literature called 'Confessions of Thugs' in 1839. However, it does not mention the historical background of thugs. The then present-day opposition to the British, the method of opposition, had been exaggerated.

After the 'Criminal Tribes Act 1871' came into effect, further amendments were made from time to time to widen the scope of the Act and this Act was enforced by the British throughout India. Many tribes consisting of lakhs of people were registered as criminal tribes under this Act. All of them together have a population of crores. According to this law, the police got the power to arrest anyone from these tribes without warrant rhyme or reason; may it be an unborn child or a dying old man, without having committed any crime. The Act provided for the arrest of all blood relatives of the convicted prisoners as criminals. Moreover, there was a provision to treat to treat the blood relatives of listed criminal as criminals. Using this law as a base, the British created terror by harassing these people endlessly. A circular was drawn up for senior executive officers instructing them to see how anti-British discontent and the freedom struggle could be weakened using the provisions of this Act. The word criminal was defined in this Act in such a way that the authorities could give it any meaning they wanted and could suppress the clandestine movements of natives against the British, especially because of the national movement that was spreading discontent against the British.

Within a short time after the 1857 rebellion in India was crushed by the British, they brought hundreds of their professors, researchers, scholars and sociologists to study the social system and the state system here. They studied the social, economic and political system of the country. Through this scientific study, they realized that the strength of the institutions here was based on the caste-class divide which was considered insignificant. The brave soldiers who fought, people who made weapons for the soldiers, artisans who repaired them, people who made uniforms of the soldiers, people who supplied the soldiers with milk, food, meat, the craftsmen who repaired the pits, creeks, hills and mountains that the soldiers marched across, and those especially faithful to the king - they all belonged to specific castes. In this army and in the class that catered to the needs of the army, there were a large number of nomadic tribes who were considered inferior in the caste system and moved from village to village through the forests. The British felt the need to build railways and roads to prevent the recurrence of rebellions like 1857 or if they did occur, to facilitate the immediate movement of British troops from North to South, from West to East.

Although the British announced railways and roads to increase trade, their priority was to facilitate the movement, transportation and management of the army. For this, the British first put into place the Forest Act in 1864. According to this Act, all the forests were owned by the government. For thousands of years before, these forests belonged to nomads. They lost out due to the passing of the Forest Act. The British government started the work of cutting down the forest and using the wealth for the construction of roads and railways. Many forest-dwelling tribes, i.e. pastoral nomads, shepherds, local cowherds, Banjaras, Gonds, Bhils, Tadvis, etc. also felt that deforestation was an attack on their freedom and livelihood and started protesting against it. The attitude of the three – the British rule, the administration and the law – was not sympathetic towards them. Now, if they touched anything in the forest, it was considered to be a crime and they would be punished. It became difficult to find livelihood and they began to starve. Ultimately tribes like Pardhis resorted to crime to survive. The scholar Nagre writes that the Pardhi community turned to crime when there was no other option, for if they did not even have access to essential food, they had to loot. The people living in these forests were not against the British, they opposed the fact that they were prevented from entering the forest, that their means of livelihood were snatched away. Those who opposed the oppressive Forest Act, which was created without taking them into account, were criminalized. Even before they came to India, the British thought that the nomadic tribes in the forest had a criminal attitude. According to their colonial policy, they believed that people who spend their entire lives hunting animals and roamed thorny forests to collect berries and fruits were merely animals. The British policy towards nomadic tribes was biased due to their presumption of their own racial superiority. According to them, they themselves were pure, civilized and superior, and the forest wanderers were inhuman and inferior like animals. A researcher named Fute writes that the British considered the people living in forests in one of their colonial countries as wild animals and did not record them in the human census until 1960. This shows how prejudiced their mentality was towards the nomadic tribes living in the forest.

If we study the details of this act, it is clear that the inhuman act was passed by the British by adopting a treacherous strategy. It is clear that the 1857 revolt against the British was behind the creation of this Act. A lot of historical evidence proves that they brought under this law the adventurous, brave tribes who fought loyally and valiantly in the armies of the local kingdoms, and also the tribes who provided logistical support to the armies, and helped directly or indirectly. We can see some prominent examples in this context.

The artisan tribes like Wadars, Odas, Beldars, Patharwats, Salats who make idols, who are skilled in building carved palaces, beautiful temples, lakes, canals, forts, roads and beautiful buildings, were turned into criminals overnight.

The British also labelled the hardworking Laman Banjara tribe, who are the descendants of Lakha Banjaras (owners of lakhs of bullocks) who have done thousands of years of inter-state trade by carrying sacks of grains, spices and salt on the backs of bullocks and who were respected by kings and institutions, as criminals.

Sufi saints of India took a different stand while fighting in the freedom struggle against the British rule. They thought of the idea of revolting against the economic power of the British. Following this lead, the 'Chhapparband' tribe launched a special campaign to create fake British coins and circulate those coins throughout India with such dexterity that the British 'East India Company' went bankrupt. And the Queen of England had to take notice of this and take possession of the company. After many years of efforts, the British finally succeeded in capturing seven prominent rebels of the 'Chhapparband' tribe. They were hanged in 1840 in 'Awadh' i.e. Lucknow after being declared thugs. Their heads were sent to Britain for a special study and research on their brain.

Almost 23 thousand suspected people who came to Awadh on the pilgrimage of Sufi saints were diplomatically killed by the British in one night. Although this event is famous in history as the Muslim Massacre, it was the killing of Muslim 'Chapparband' people. They did not mint coins of any kings or institutions other than the British. They were not and are not accused of theft, robbery, hooliganism, murder, burglary etc. They should actually be called freedom fighters who fought against the British. But they were considered to be born criminals.

All the above nomadic communities were registered by the British as criminals by birth under the said Act in such territories as they deemed necessary.

- Balkrishna Sidram Renke

Interview and Transcript: Prof. Sunita Chawala

Translation: Rahee Dahake

Tags: nomadic tribes independence anniversary sadhana digital independence day 15th august kaalche swatatntrya... balkrishna renke Load More Tags

Add Comment