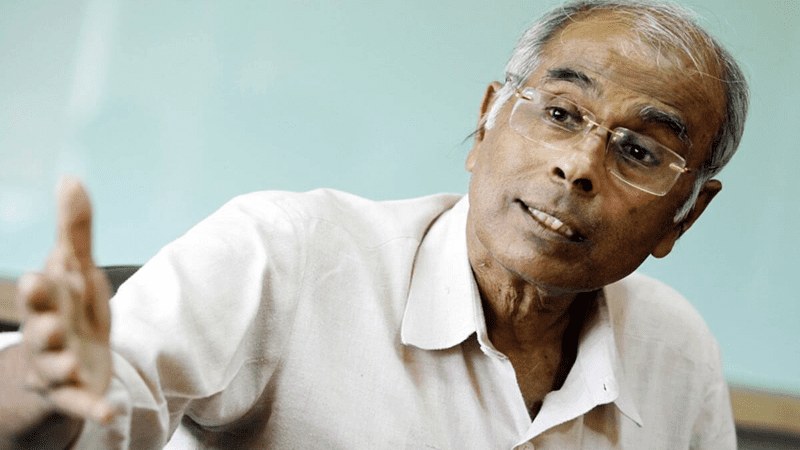

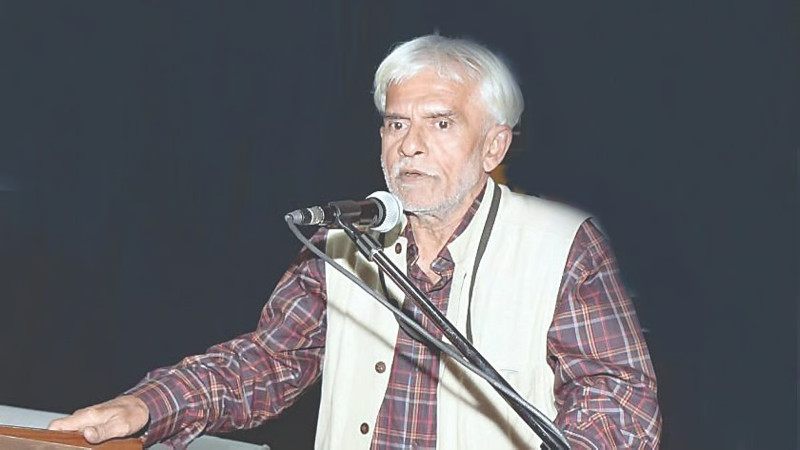

Dr. Narendra Dabholkar was born on November 1, 1945. Had he been with us today, the spearhead of India's rationalist movement would have embarked on his 75th year of age. When he was assassinated during his morning walk, he was very close to completing 68 years.

Coincidentally, just a few months before that, he said to me during various chats, “The average life expectancy in India is 67… which is a milestone I have already reached. Each day is a bonus from now on. However, as long as an incurable disease or mishap does not interrupt, I should be able to maintain my present output until I turn 75”.

Once we were speaking about the new-wave killer diseases. “If I were to be ever afflicted by one of them, I am sure there are many doctors among my friends and family, who will leave no stone unturned to cure me. But I would not like to accept any special care that is not accessible to the common man”, he expressed.

Dr. Dabholkar was also in favor of legalizing euthanasia but never actively campaigned in its favor. Being a doctor, he too was aware of the risk of malpractices, if euthanasia were to be legalized in India. But during chats with friends, he would speak passionately in favor of euthanasia. Especially after visiting a terminally-ill friend or family member. I could sense that something was brewing in his head about the medical, philosophic, and literary dilemmas of euthanasia.

Dr. Dabholkar observed a punishing daily regime. He inevitably woke up at four each morning and did his physical exercises – no matter where he was - at home or some remote residential workshop for budding rationalists. He made no exception even in travel. He could make do with very little space for exercise - in a moving train, or even a modest state transport (ST) bus service stop. So large was his activists' base that he always stayed with friends during travel. But on very rare occasions in forty years of public life, if ever he stayed at a hotel, his exercise regime would brook no excuse.

The exercise was followed by a cup of tea and a walk. At six, he would be ready to take on his day: make that seven, if he had arrived late from a tour the previous night. Ordinarily, the day used to end at 10 PM. Meals were at 1 PM and 8 PM and food preferences were simple. No special insistence on sweet, spicy, or savory. An occasional dish of fish or meat was welcome. He would have tea, thrice a day. Any other 'vices' were unthinkable.

Dr. Dabholkar divided his day judiciously between reading, writing, strategizing work, travel, and meetings. He was punctual to a fault. His jam-packed diary would inevitably accommodate a few extra engagements, without missing a single appointment.

I once said to him in jest, "I'm not surprised you keep your appointments. I am surprised that even public transport falls in line for you." He was a tireless traveler. When people asked him where could he be mostly found, he replied in a lighter vein, "On an ST bus."

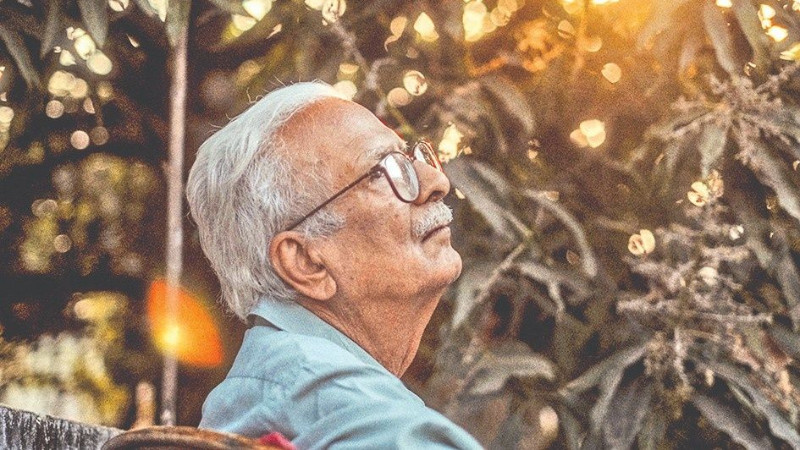

"Doctor, what if age ever put restrictions on your travel?", I once asked him.

"Easy. I'd settle down in my native Satara. I'll start a kabbadi coaching academy to impart scientific coaching in kabaddi," he replied.

Dr. Dabholkar had been a kabaddi player for 15 years, from age nine onwards. As a player, he spent as much time on the kabaddi grounds, as he spent at school or home. He didn't just play the game, he evangelized it, trained others, prepared fields, did commentary, or refereeing. He bagged the state sporting excellence Chhatrapati Shivaji award twice - once for his sporting performance, and the second time for his all-round contribution to the game. Top politicians like Sharad Pawar and Shriniwas Patil still remember Dr. Dabholkar as a kabaddi player. His book on the scientific methods of learning kabaddi was published by the state literature and cultural committee and had a foreword by Sharad Pawar, then minister of state for sports.

At a time when international kabaddi tournaments were just introduced, Dr. Dabholkar was selected into the Indian team, for a tour of Bangladesh (then East Pakistan) in 1971. But war broke out between India and Pakistan, and the series was called off. A year later, Dr. Dabholkar quit kabaddi as a player.

Come to think of it, had he been with us and returned to start a kabaddi academy at 75, it would have been an even more amazing life. Not only would he have mentored several international kabaddi players for India, but also his life would have achieved a rare symmetry - 50 years of solid social reform, offset at both ends by years of dedication to kabaddi. That, alas, is a conjecture.

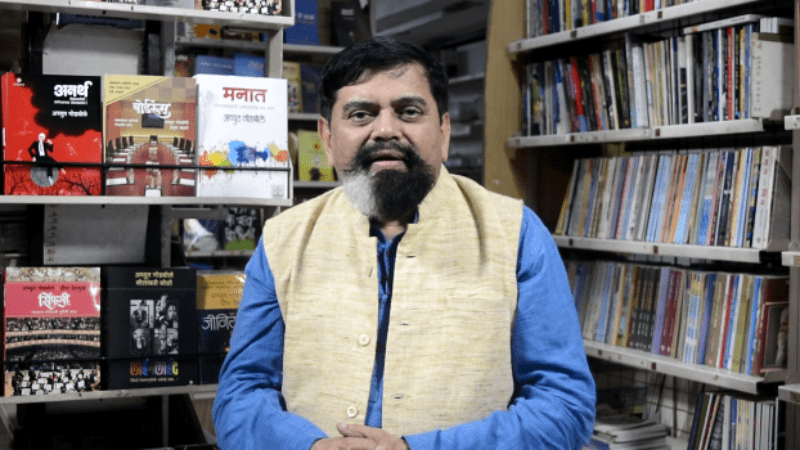

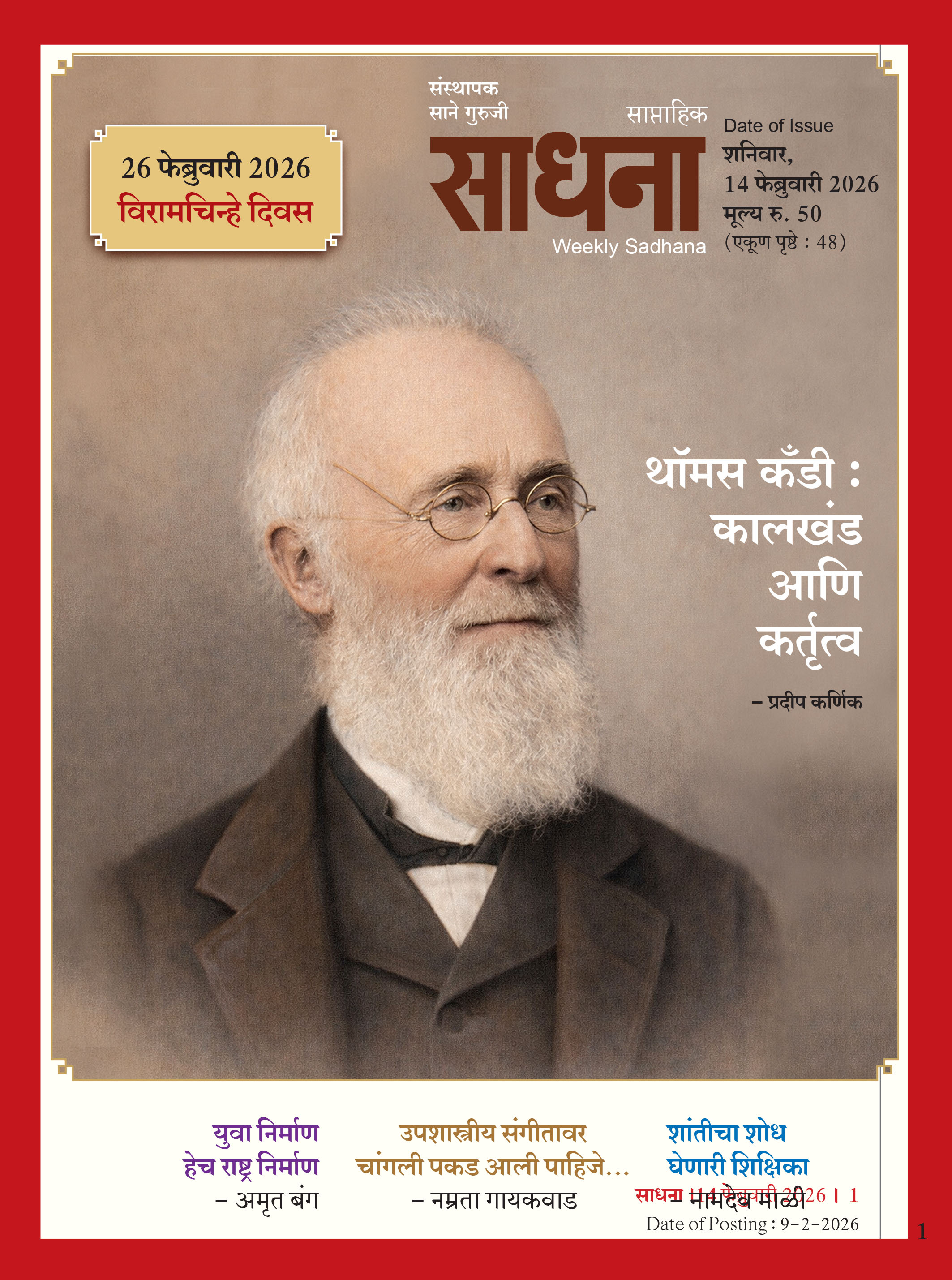

Dr. Dabholkar's public life spanned more than four decades, the last three decades of which were devoted to his rationalist movement, Maharashtra Andhashraddha Nirmulan Samiti (MANS). The last 15 years were also prominently devoted to vibrantly driving Sadhana weekly. On his first memorial day, Sadhana published an article I wrote about how he contributed to Sadhana’s growth. I feel, there is material worth at least one more book on that subject. As for MANS, Dr. Dabholkar himself penned 12 books and left behind material for a few more volumes. Last year, three of his titles were published in English, and six in Hindi. In the next few years, his other books will also be translated in Hindi and English. These books are on topics that are not available in any other Indian language. That is because Dabholkar's writings emanate from his activism. Rationalist movements of such depth and spread are yet to take shape in other states.

Alas, other states too have dogmatic practices and superstitions arising out of ignorance and fraudulent godmen. Faith itself is on the decline. It's leading to financial, psychological, and sexual exploitation. There is a need to spread a scientific temper even in those states. The rise of strong rationalist movements and leaders is imminent in those states too. The search for the rationalist legacy in India is bound to lead them to Dr. Dabholkar and his writings. It is therefore critically important to have those writings available in Indian languages. Who knows, technology would perhaps help us dub his speeches too in other languages!

This project could take us another 25 years to spread Dr. Dabholkar's word through the land. It would be his centennial year.

And what thereafter?

There are so many countries, say for example in Africa, who need rationalist reform. Technology is rapidly reaching them and introducing a social churn. A new flank of social reform champions is bound to come up there too. They too face the dual challenges of superstition and exploitation. They too seek a solution that reconciles faith and science in the service of society.

If they search the globe for like-minded social warriors, they will inevitably discover Dr. Dabholkar and MANS. This too may take another five to seven decades. And, say, people would be celebrating Dr. Dabholkar's sesquicentennial year.

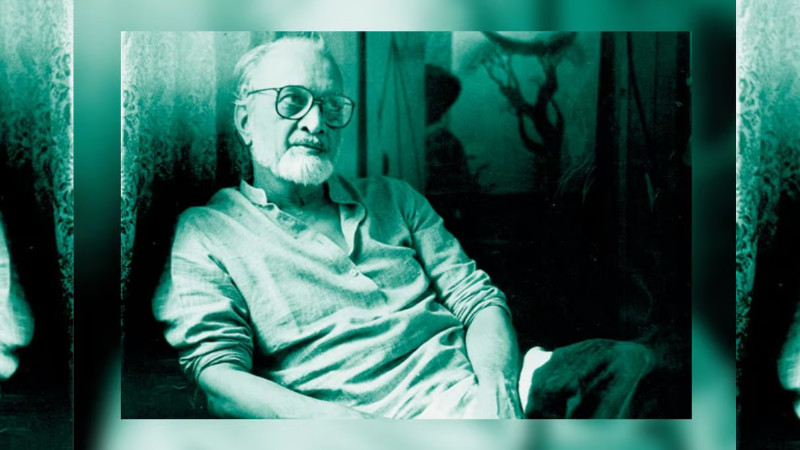

Then too, people may reflect on Dr. Dabholkar's autobiographical account of his endless path, 'Ek Na Sampnara Pravas'. They would be struck by his line, "In the field that I work, I am aware that one has to plan for centuries, not decades." A few young Marathi activists of today could well be around to witness that day and appreciate the journey.

In short, Dr. Dabholkar's killers died the day they planned to assassinate him. But Dr. Dabholkar is alive even today!

- Vinod Shirsath

editor@kartavyasadhaa.in

The article was initially published in Marathi on Kartavya Sadhana, on 1st November 2019. Translated by Sanjay Pendse.

Tags: narendra dabholkar dr narendra dabholkar vinod shirsath sanjay pendse editorial संपादकीय Load More Tags

Add Comment