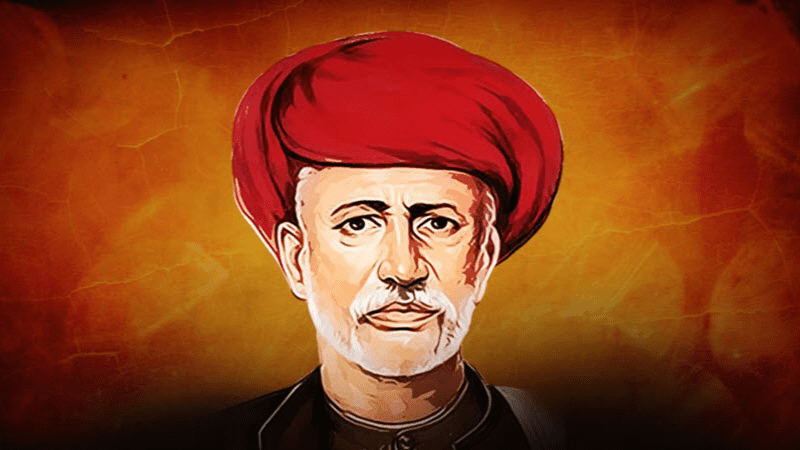

Louis Fischer’s book ‘Mahatma Gandhi: His Life and Times’ was published in 1951. (The book is rather famous with its alternative title: ‘Life of Mahatma Gandhi’.) Sadhana Prakashan published a Marathi Translation of the book recently, and the translated book is received well by readers. But there is another important book by Louis Fischer about Gandhi that we will talk about today. When Fischer first visited India in 1942, he had spent a week in Sevagram Ashram in Gandhiji’s company. A diary of that week was published with the title ‘A Week with Gandhi’. An article introducing the diary was published in Sadhana Weekly issue dated October 2, 2005. The article, still important and relevant, was then published in a column addressed to the youth, and is now included in the book “Third Angle” published by Sadhana Prakashan.

~ Editor

"There is something of the dictator in him when he wants action. Then he crushes opposition by the weight of his logic and the strength of his popular following. But there is nothing of the dictator in his thinking. A dictator can never admit he is wrong. Gandhi can; he often does."

Practical Friends,

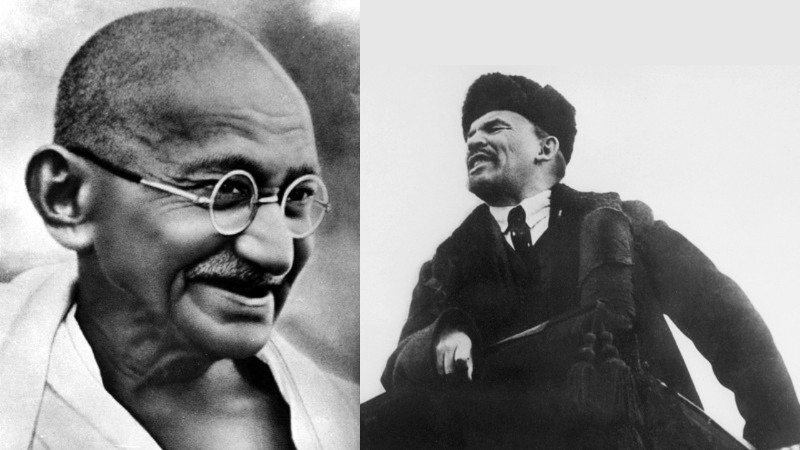

A few months ago, a practical friend, who wasn't a part of the "Practical Club," asked me, "How does Gandhiji look from the third angle?" Without thinking much, I quickly replied, "Just like he appeared to Louis Fischer!" I thought a lot about that question later but didn’t feel the need to change my answer. You might ask, "Who is this Fischer?" It’s obvious that Louis Fischer wasn't Indian, but he wasn’t British either. He was an American journalist who spent fourteen years in Russia. He had closely observed the socio-political scenes of both communist Russia and capitalist America. Fischer had served two years in the military and wrote for The Washington Post. He had close connections with many world leaders. His key strength was offering commentary through unbiased observation, deep study, and uncanny analysis. Since he had seen some of the world's greatest leaders up close, he managed to avoid both idolization and condescension. This is precisely why Richard Attenborough chose Fischer's biography of Gandhi as the primary source for his film Gandhi.

Fischer, who had gained worldwide fame for his book Men and Politics, became better known later as the author of Life of Mahatma Gandhi. His subsequent books include Gandhi and Stalin and Stalin and Hitler. One of Fischer's most underrated but highly significant works is A Week with Gandhi. This book serves as an excellent example of how to observe a great person when given the opportunity to spend time with them.

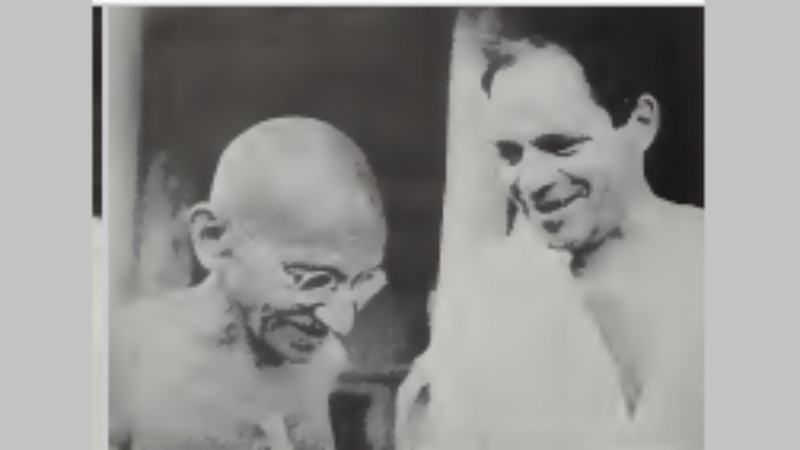

Although Fischer was a world-renowned journalist, his first meeting with Gandhi occurred only in June 1942. From June 4 to June 10, 1942, Fischer stayed at Sevagram Ashram with Gandhi. His daily schedule involved morning and evening walks with Gandhi, having lunch and dinner together, and interviewing Gandhi for an hour in the afternoon. Fischer kept a "stenographic record" of his observations, discussions, and thoughts during those seven days, which later became his diary. This very diary was published as the book A Week with Gandhi. Carl Heath wrote a half-page preface to the hundred-page book. Heath said, "This book successfully removes Gandhi from a 'semi-mystical’ atmosphere." And that's true. This book is a must-read, not only for its language, style, and thought but also for understanding what Gandhi was thinking just two months before the Quit India Movement on August 9, 1942. Reading the records of Gandhi's eating, walking, talking, and daily life gives us the 'feel' of being in his presence. Fischer, a sharp journalist, admits, "I learned a lot from Gandhi, and about Gandhi, during those eight days."

At the end of their first interview, Gandhi told Fischer, "I am very imperfect. Before you are gone, you will have discovered a hundred of my faults, and if you don't, I will help you see them." Their dialogues afterward were an intellectual battle between two cultured minds from different worlds. The mutual respect, the willingness to change one's views, and the honesty to admit it were remarkable.

After the second day's interview, Fischer wrote, "Today's interview with Gandhi has historical significance. He changed his opinion on a burning issue." Gandhi had previously said, "The British should leave and leave us to God." But now, he changed his stance to, "The British can stay here and continue the war with Japan and Germany." One of Fischer's questions had prompted Gandhi to change his view.

On the third day, Fischer asked directly, "It's said that Congress is influenced by industrialists and that these same industrialists fund Gandhi. How true is this?" Gandhi plainly admitted, "Unfortunately, it’s true." Fischer further asked, "How much of Congress's expenses are covered by industrialists?" Gandhi answered with the same candor, "Practically all of it."

When the subject of Subhash Chandra Bose came up, Gandhi described him as both "a Patriot of patriots" and "Misguided." He openly stated, "I opposed him and kept him away from the Congress presidency twice." Even when Fischer showed sympathy for Bose's idea of seeking foreign help to free India, Gandhi firmly said, "I do not want help from anybody to make India free. I want India to save herself!" Reading this statement in its full context could help reduce some of the opposition to calling Gandhi the "Father of the Nation."

The book is filled with great examples of witty and intellectual exchanges. On the last day, Gandhi complimented Fischer with, "You are a fine listener," and Fischer, in turn, told Gandhi, "I have slept better than I had for many years," creating a sense of mutual respect and admiration between them. This deep and true admiration makes the diary-like book so compelling that one feels the urge to read it repeatedly.

At the end of the book, under the title "Comments," Fischer writes a seven-page discourse that brings up Gandhi's inner self and shows the core of his personality. While the entire commentary is worth reading originally, the central idea in Fischer's own words is as follows:

At the end of the book, under the title "Comments," Fischer writes a seven-page discourse that brings up Gandhi's inner self and shows the core of his personality. While the entire commentary is worth reading originally, the central idea in Fischer's own words is as follows:

"Part of the pleasure of intimate intellectual con- tact with Gandhi is that he really opens his mind and allows the interviewer to see how the machine inside works. When most people talk, they try to bring their ideas out in final perfect form so that they are least exposed to attack. Not so with Gandhi. He gives immediate expression to each step in his thinking. It is as though a writer were to publish the first draft of his story, and then the second draft, and ultimately third and last draft. Readers might protest, and claim that the plot had been changed, that the popular lover had been transformed into a villain, and so forth. Gandhi would not listen to such protests. He would say, “Yes, I changed my mind.” Actually, he thinks aloud, and the entire process is for the record. This confuses some people and impels others to say he contradicts himself, or that he is a hypocrite. Gandhi does not care. Maybe he is too old and impersonal and not of this world to bother about the impression he makes. Many Indians and Englishmen in India, when I interviewed them, cautioned me that their words were not for publication. Gandhi never worried about what I would write about him or how I would quote him. He did not talk at me; he talked to me. I spent many hours with Mohammed Ali Jinnah, the President of the Moslem League of India. He is a brilliant parliamentarian, a skilled debater, and an incorruptible politician. But he talked at me. He was trying to convince me. When I put a question to him, I felt as though it had turned on a phonograph record. I had heard it all before or could have read it in the literature he gave me. But when I asked Gandhi something I felt that I had started a creative process. I could see and hear his mind work. With Jinnah I could only hear the needle scratch the phonograph record. Jinnah gave me nothing but his conclusions. But I could follow Gandhi as he moved to a conclusion. He is, therefore, much more exciting than Jinnah.

If you strike right with Gandhi, you open a new pocket of thought. An interview with him is a voyage of discovery, and he himself is sometime surprised at the things he says. His secretaries, who sat with us as he spoke, were often surprised at the novelty of his assertions. That is why I learned so much from Gandhi and so much about Gandhi. He did not merely give me fact and opinions. He revealed himself. He also supplied one with am- munition against himself. Gandhi did not have to tell me, for instance, that he had ascribed qualities to his weekly day of silence which he knew it did not possess. But that is Gandhi. His brain has no blue pencil; he doesn't censor himself. This makes him a baffling or even irritating person to some politicians."

“There is something of the dictator in him when he wants action. Then he crushes opposition by the weight of his logic and the strength of his popular follow- ing. But there is nothing of the dictator in his thinking. A dictator can never admit he is wrong. Gandhi can; he often does.”

Fischer's works, particularly 'A Week with Gandhi', shed light on many misunderstood aspects of Gandhi’s personality. Through these detailed accounts, we get a clearer sense of why Gandhi’s life and words are often misinterpreted.

My Dear Practical Friends,

On the occasion of the 136th birth anniversary of Gandhi, understanding him better or clearing the misconceptions around him can be best achieved through Fischer's books. I elaborated on this point to leave a strong impression on your minds. While I used English quotes throughout, it was necessary and also my limitation.

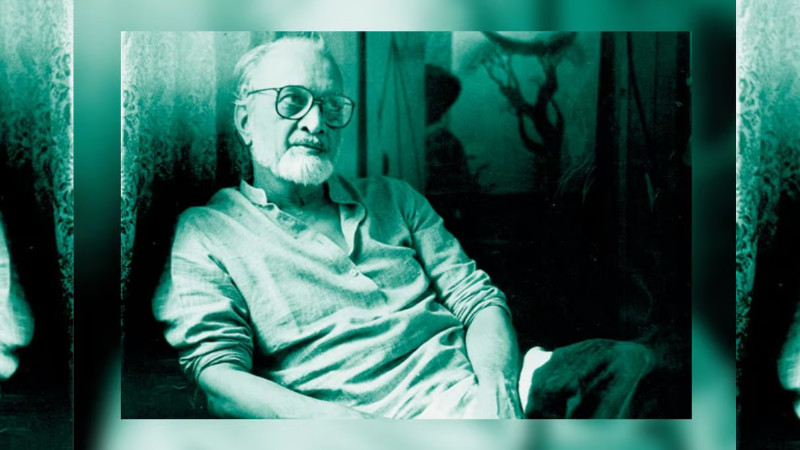

- Vinod Shirsath

(Editor, Sadhana Weekly, Sadhana Prakashan and Kartavya-Sadhana)

kartavyasadhana@gmail.com

(Translated by Rucha Mulay)

Read the Original Article in Marathi Here: गांधींविषयी इतके गैरसमज का आहेत?

Tags: sadhana digital Gandhi mahatma mahatma gandhi A week with gandhi Load More Tags

Add Comment