The five-day bonanza festival of Nirmaladevi is over and at the end, you realize that except the expansion of MGNREGA and five-kilo free ration for a short period, (incidentally, MANREGA and Food Security both being legacy of UPA era) the poor of India get nothing, not even another five hundred note in the Jan-Dhan this time, after trudging those long ‘atmanirbhar roads’ barefooted under the scorching sun, as first lessons of PM’s Naya Bharat.

The Big Bang package has turned out to hardly 1.1 % of GDP this financial year. Every section, from industrialists to workers and majdurs feels cheated. A friend forwarded me a picture, a mesh of jumbled wires on a pole. “If you can figure out which wire connects to which unit, then you can tell what Mrs. Sitaraman said”, reads the caption. The poor lady, why blame her? Actually, the picture depicts the state of the whole Indian State. After this, don’t ask how we are going to win this war on mahamari.

Meanwhile, the palaayan of the migrants that was triggered by the PM’s address on the night of 23rd March is surging towards the red mark of two months this weekend, when the monsoon is at doorsteps. Nearly seven hundred migrants have lost their lives on the roads, mostly in rash accidents but many of just hunger, volunteers report.

Meanwhile, the palaayan of the migrants that was triggered by the PM’s address on the night of 23rd March is surging towards the red mark of two months this weekend, when the monsoon is at doorsteps. Nearly seven hundred migrants have lost their lives on the roads, mostly in rash accidents but many of just hunger, volunteers report.

There are no people on the road, government pleaders had said, and it must be true as the top court of the land readily believed. There are definitely no human beings now, only the jinda murdas (living corpses) carrying their own rickety bodies to graveyards in their maybhumi.

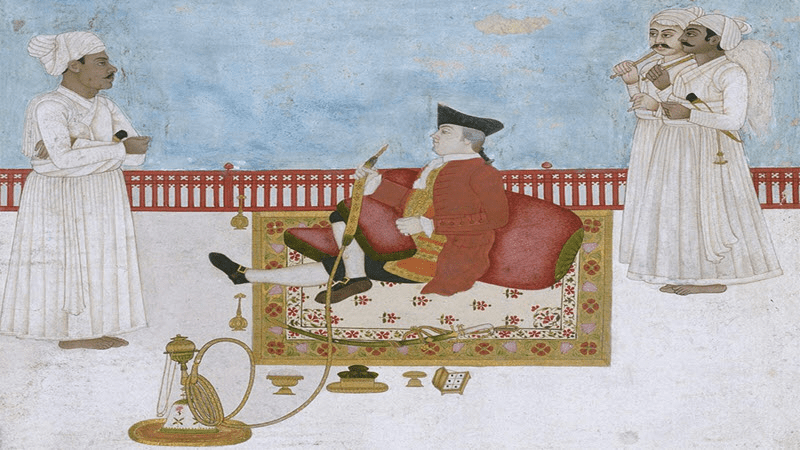

This desolate march prompts me to mull over a distant episode in our early colonial legacy, graphically described by William Dalrymple in his recent book, ‘The Anarchy: The East India Company, Corporate Violence, and the Pillage of an Empire’.

Indian history is dotted with repeated occurrences of famines accompanied by diseases. After Plassey, severe conditions developed in the newly won dewani, marking one of the great famines in India.

During the earlier Mughul regime, “elaborate systems of grain stores, public works and famine relief measures had been developed to blunt the worst effects of droughts” and now many of the Mughul administrators took initiatives to set up gruel kitchens. Among them, the work of Shitab Rai, the Governor of Patna was acclaimed by historians.

“Shitab Rai, melted by the sufferings of the people, provided in a handsome manner of the necessities of the poor, of the decrepit, the old and the distressed”, noted contemporary historians. The Governor did two things. First, he commissioned boats belonging to his household and imported rice from Benares market where it was available at cheaper prices. The grains were sold at purchase price, the charges for transportation, losses, etc being borne by the Governor. Nearly for two years, the boats divided into three groups continuously ferried rice. Hordes of hungry people flocked to the granaries from all parts.

But there were many more who could not afford even the cheap grains, and Governor opened for them camps in four-walled gardens, watched by guards, but attended as patients by the staff, Servants brought food at a regular time, cooked for Muslims, and dry rations of different grains and pulses, etc for Hindus, who would be provided with earthen vessels and firewood. At the same time, several ass loads of small money and a certain quantity of bhang, tobacco, etc were distributed to the poor.

This continued to happen “every day and without fail” till the conditions prevailed. The Governor spent thirty thousand rupees on the programme that Dalrymple converts into 3, 90000 pounds today.

Hearing reports of such generosity, some officers of East India Company Government were moved to take steps to mitigate the sufferings of people. But the overall approach of the Company Sirkar remained ignorant, aloof, and even insensitive. Dalrymple reports:

“The administration took up no relief works, nor did it make seed or credit available to the vulnerable or assist cultivators with material to begin planting their next harvest, even though the government had ample cash reserves to do so. Instead, anxious to maintain their revenues at a time of low production and high military expenditure, the Company, in one of the greatest failures of corporate responsibility in history, rigorously enforced tax collection and in some cases even increased revenue assessments by 10 percent.”

The worst effects of this policy were to follow. The writer tells us that platoons of sepoys marched into the countryside to enforce payment, where they erected gibbets (or gallows) in prominent places to hang those who resisted tax collections. Even starving families were not spared. On the other hand, individual company traders forcefully purchased grains and engaged in hoarding, profiteering, and speculation. At many places, the (white) Gentlemen purchased the rice at 120 or 140 seers for a rupee and afterward sold it for 15 seers for a rupee to the black (Indian) merchants.

By the summer of 1770, streets of Calcutta were littered with deads, and the Ganga was flooded with infected bodies. Lakhs of poor tillers lost their lives.

In the year 1770-71, home remittances by company officers jumped to 1,086,255 pounds or 100 million pounds in modern currency. And the Governing Council of the Company noted with satisfaction that the tax collections were violently kept up to their former standard.

Such was the regime of Company Bahadur Sirkar.

- Subhashchandra Wagholikar

(The author is a journalist stationed at Aurangabad. He can be reached at subhashchandraw@yahoo.co.in)

Tags:Load More Tags

Add Comment