Rajiv - the person and the friend

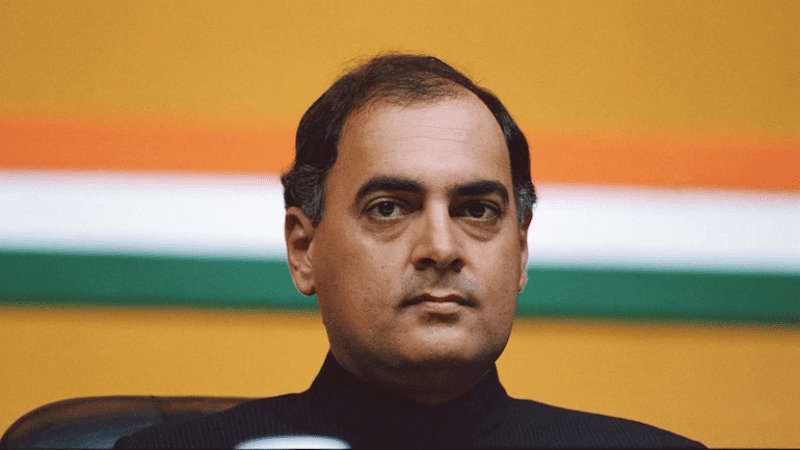

On 21st May 1992, Rajiv Gandhi’s first death anniversary, a memorial meeting was called by Mrs. Sonia Gandhi of about 35 to 40 professionals working closely with Rajiv during his tenure as the Prime Minister and later, as the Leader of Opposition in the Lok Sabha. I was sitting next to her and was the last person to speak. It was at this instant that I suddenly realized that everyone present in the meeting had met Rajiv Gandhi, the Prime Minister. I was the only one among them who had been with Rajiv long before he entered politics. Rajiv also was a personal friend to me. He was always Rajiv to me and Rajivji to all others. Everyone had spoken about the late Rajiv Gandhi, the Prime Minister - covering every facet of Rajiv as a young, honest, and progressive technology-savvy PM. Some a little closer, admired his charming personality, agile mind, quick-witted responses, his openness, and his achievements. So, I said very little and summed up by saying, “Rajiv was my close friend since 1974 and I always feel deeply sorry that he had to assume the role of Prime Minister too soon in his political life and unfortunately we are all unlucky to lose him too soon.”

Premature responsibilities thrust on him hurt Rajiv as a person like nothing else. People were fed up with manipulative politicians and their sleazy tomfoolery. Therefore, despite his political inexperience and a kind of naive in handling matters of diplomatic importance, he immediately became a popular and endearing icon. His image as a charming honest young man and his refreshing presence had enabled the Indira-led Congress to win a landslide victory with over 80% seats in the 1984 Lok Sabha. Roots of his post-1987 problems can be traced to his nature. Scheming political colleagues and bureaucratic manipulations were a little too much for him to handle. He could not cope up with the motivated revolt of the cunning colleagues and allegations of corruption. By then, he was not sure about anyone, not even his friends.

Two years of being out of power had changed this. Rajiv spent the first half of 1990 analyzing exactly what went wrong. On the day he became the Leader of opposition, I met him in parliament. We talked and he was frank enough to admit that he made mistakes but also said that he had little time to learn how the system works.

I first met Rajiv, the Avro Pilot, on a rainy afternoon in Mumbai a couple of days after his birthday in June 1974, a year before the emergency. He was born on June 20, 1944. Our common friend, Audio Equipment Professional Manu Bhai Desai, the owner of Cosmic Radio, had arranged for us to meet. The reason was Electronics, the glamorous emerging technology to link us together for the next 16 years. As we shook hands, his exceptionally handsome and gentle face broke into a smile as he said ‘Hello’. I did not know then that his winning smile was later to charm an entire nation. His smile was very rare. It had the innocent charm, the warmth, and genuineness that would win over anyone’s confidence. It took only a couple of meetings and an early sizzler dinner at the Touché Restaurant to turn our acquaintance into a long & close friendship. While electronics and computers were its bedrock, our friendship grew closer week after week when we met during his layover in Bombay as an IA Pilot.

Till the untimely death of Sanjay in 1980, there was no place for politics, politicians, bureaucrats, or the politically inclined in Rajiv’s circle in Mumbai. All these were scrupulously avoided. Often, we would try and give a slip to the mandatory security to this son of the most powerful person in the country. In any case, his low profile resulted in very few recognizing him as we moved together everywhere almost incognito. We went to Lamington Road, or moved through Vileparle Bazaars for this or that, but he remained largely unnoticed. Gokul Ice-cream was often a post-dinner luxury.

Rajiv possessed a techno-savvy inquiring mind and had an inquisitive urge for knowing more about techniques or innovation in a wide range of modern and fast converging technologies like micro-electronics, communication, and computers. Interestingly, however, Rajiv also showed a keen interest in social issues hurting people at the grass-root level. As he rubbed shoulders with common people while moving with us in Mumbai, we often ended up thinking of solutions about this and that, and about life in general in India. He even willingly offered to visit a public hospital to meet someone ailing from our friend circle. Looking at the face of our ailing friend, I believe that his charming reassuring smile gave her immense relief.

The five years till 1980, and the several hundred days we spent together, helped Rajiv experience a different world. He didn’t ever smoke, or drink even a beer, but often sat with us in evenings as we had a drink or two since our discussions invariably ranged on debating options related to various social and cultural ideas.

He was sincere and disciplined in everything he did. He was also a devoted husband though he charmed women as equally as men. He had a dignified, but a clean informal presence, that nipped any cheap talk in the bud. Even in those days, he was the people’s prince in his own right. The canteen boy in our factory would almost melt when he unfailingly got a smile with a nod from Rajiv as he accepted his plate. All our friends, who often gathered at Manu Bhai’s place across the Santacruz Airport, were his great fans. They loved him because he hated politics as much as they did, despite being the son of the most powerful politician India has ever produced. Those were the days of learning, living, and loving the common man’s world that later came in handy as his responsibilities grew to manage the country.

The most charming part of his persona was not having any air in him of being a son of India’s most powerful person. Even as a pilot, he was professional in his work but never overstepped his position in the organization. Leave aside benefiting in any way from his enviable lineage and the Gandhi heritage, Rajiv did not want to use his immense shadow power even for a good cause. During the unfortunate days of the emergency, the father of a family friend of mine from Pune was taken away by the police due to his political links. This friend was anxious to know the whereabouts of his father after having no news of him for 10 days. I asked Rajiv whether he could ask police officials for the arrested person’s safety. When he declined, I was a bit upset initially, but later Rajiv explained that such a thing will lead to his involvement and use of influence. The most important thing I admired about Rajiv was this inner strength to remain politically isolated while being very caring about his mother.

Rajiv lived in the PM House at 1, Akbar Road, but had his separate living areas. He lived very simply but tastefully. His bookshelves were lined up with books on technology and engineering. A music system occupied most of the small living room. Music was his main pastime in Delhi - and he liked both Western and Hindustani classical music, and film music was not wholly unwelcome. His other interest was Amateur Radio, and also Electronic Gizmos. All these were common bonds between us.

Rajiv, Manu Bhai, and I were bound by our common love for electronics technology and its potential. The first reasonably serious Home Computers were BBC Sinclair ZX80, ZX81 and Spectrum that appeared one after another between 1980 and the end of 1981. We together bought ZX80 kit and later ZX81 and Spectrum with 128K RAM and used them patiently.

Our IT education and fascination thus became hands-on! He also indulged in serious photography. Flying however was his passion and a preferred profession. Our common friends in Indian Airlines vouched that he was a great pilot who also knew a lot about what’s what in the guts of his greatest love, aircraft.

Rajiv was a very private person. He guarded his thoughts and controlled his expressions with ease in those days. In his later years, he picked up a wrong habit of making occasional smart remarks from our friend Mani. The press was quick to catch on those to embarrass him. He was very friendly and everyone felt close to him, but it took years for me to get a shade closer to him and have a glimpse of his private self. He had a difficult childhood and had learned to live within himself. He had the cultivated art of keeping a cool and peaceful front. He controlled his anger from others, but the reddening of his ear lobes gave it all away. I could easily sense his suppressed anger and discomfort in meetings.

During the post-emergency days, we came much closer. His relationship with Sanjay had deteriorated to a new low. He was deeply affected by his mother's troubles after her political defeat in 1977. He felt that Sanjay was responsible for her political problems. He also disliked some notable others like Dhirendra Brahmachari around her. But he was very protective of her. I think that they both came closer like never before during those extremely trying times for her.

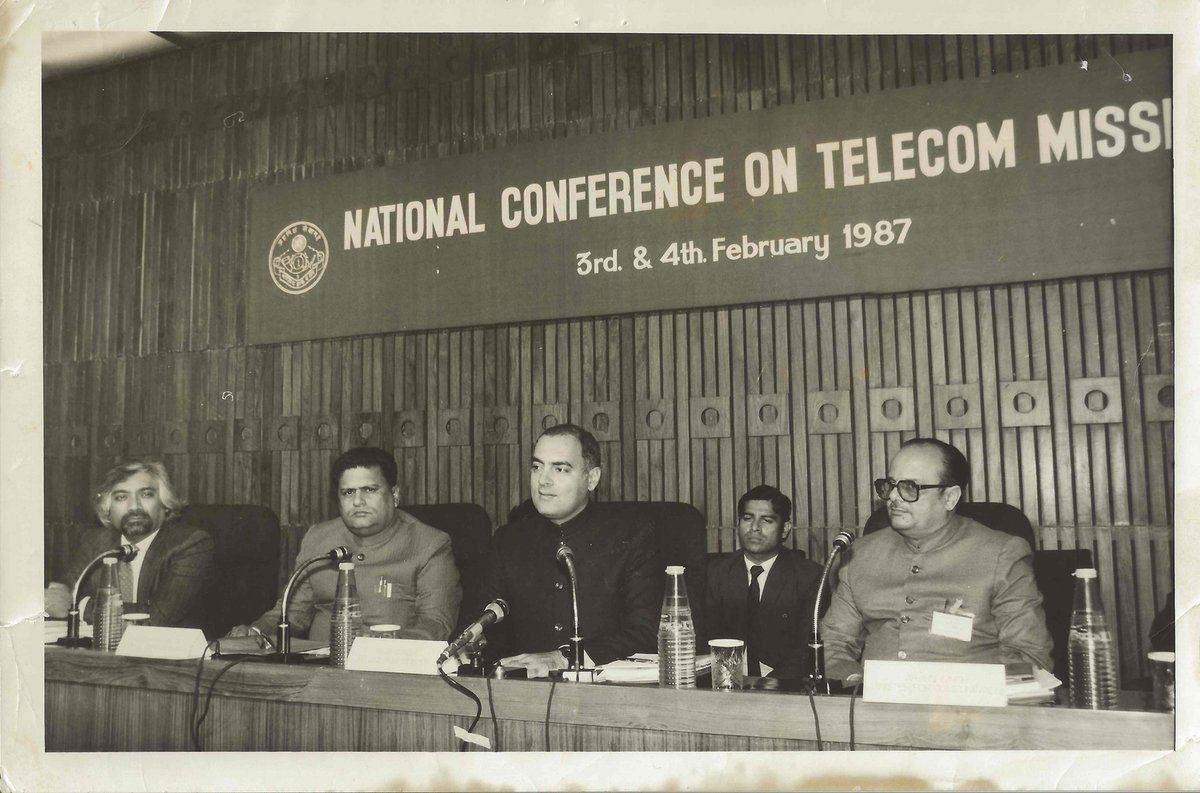

Rajiv – The Prime Minister

I saw less of him after he became the Prime Minister. However, he would call me occasionally for a five-minute meeting that often stretched into an hour. We also met on Aircraft when he was touring. That gave us some quiet moments. I would write to him many comments and he responded often with his opinions. Till the end, I used to address him as Rajiv. Sometimes even during official meetings, I would occasionally slip and call the PM of India by his first name. He would smile and respond but I would curse myself for my indiscreet behavior. Rajiv was never comfortable in the company of politicians till the end. Till he entered politics, he had seen how the senior party leaders behaved - he saw hidden behind their lachari, was a cunning mind with a private agenda. We talked of it rarely but his dislike grew more intense during post-emergency days. It took some time to persuade him to meet Sharad Pawar and hear him out before Pawar rejoined Congress. The day he took over as the leader of the opposition and was moving his stuff in his new room in the Parliament, I said to him that he must be feeling free of a great burden in his new role that allows one to find faults but not perform. In childlike simplicity, he exclaimed, “No Prabhu! I am now afraid that all my excuses to avoid politicians are gone. I am worried, Prabhu!”

As a young Prime Minister, Rajiv faced many unenviable challenges. He had a plethora of problems to resolve. Political and religious violence in Punjab and the Northeast, a sagging economy in terms of diminishing reserves and lack of adequate budget control, a demoralized Congress (I), chronic tensions with Pakistan and Sri Lanka, etc. left little time for fixing the far-reaching basic inadequacies like the urban-rural divide, education, and healthcare. The first two years were wasted partly in honeymoon and bringing temporary calm. Intra-party politics by power brokers was hurting too. I had seen him exasperated and tense after meeting regional party bosses. The huge mandate gave him enormous democratic power that he wasted mostly out of inexperience.

Bureaucrats were the main bottlenecks in our efforts to change. That has been the only time when someone had the mandate to change even the constitution and reform it to eliminate developmental blocks. But finally, and very unfortunately, 82% majority proved to be a wasted mandate. In many ways, he was different and better than his mother. Rajiv believed in conciliation and not confrontation, he depended on well-educated friends and did not build a coterie around him, and he offered change but with a kind of continuity to Indiraji’s rule. But he finally realized that everybody with him projected their aspirations and wishes on him.

The pace of economic reforms and policies to stimulate private investments was therefore slow. I could however ensure his focus on technology and new electronics, and our software policies were widely appreciated. We were doing our job by achieving a 40% annualized growth of electronics and IT output. US multinationals and European corporations came forward with investments in software development. We set up four IT Parks - and with that Bangalore was set in motion.

A letter from Sam Pitroda in 1981 to Indiraji came to Rajiv, and then me for comments. Later, Rajiv agreed to create CDOT for Sam, much against the DoT resistance. It proved to be a major step towards reforms in telecommunications, especially to link rural and urban India.

But the bureaucratic stronghold was throttling with manipulations by babus to delay reforms that would eventually reduce their hold over industry and spell death for the license-quota raj. The commerce Ministry under Dinesh Singh was creating numerous roadblocks. I was fed up. Cunning bureaucrats had taken away the powers of the Government given to the Electronics Commission just a month before me taking over. I realized this within days but there was no way to reverse it. So, it became a toothless body.

After two years, I advised the Government to dissolve the Electronics Commission as it was a waste of time to be an advisor. As they say of advice; the wise don’t need it and the unwise don’t heed it. Then Rajiv called me to say whether I was leaving him. He was already in trouble and I had no heart to desert him. So, I became his Advisor - still in the Rank of a Minister of State, but to me, it was more important to be by his side. The change of ministerial portfolios too was proving to be counter-productive. It was not my domain but I spoke with him against it a couple of times. Finally, Madhavrao Sindia was the only minister to last the full term in his ministry. By early ‘87, it was clear that VP Singh had his own agenda. As someone has written, he had good intentions, showed some progress, but was hurt due to weak implementation and poor politics. And then suddenly out-of-the-blue, came the Bofors Scandal that hit Rajiv and his government like a tornado.

That scandal ultimately proved to be his cruel undoing. It hit him below the belt. He lost trust in nearly everyone. He was no Indira to deal with such situations. The system was taking its toll. This was severe trauma, especially since he was wholly innocent. In the process out of a misunderstanding, he lost Arun Singh, and that too hit him hard. Arun Singh was after all his classmate at the Doon school. Both were the same age and he joined Rajiv in 1981, just before he became an MP from Amethi. He was also Rajiv’s neighbor in 7, Race Course Road with just a wicket gate separating them. Indeed, this was the time he mostly needed men like Arun Singh, and not sycophants and the time-servers he had around. Luckily, Arun Singh has later clarified that he parted from his close friend since he felt he lost Rajiv’s trust.

After 18 long years, and after successive opposition Governments in power going after the Bofors payoffs scandal, Rajiv has been finally absolved of the charges by the Supreme Court. I, however, never believed that Rajiv personally had anything to do with Bofors. I had several strong reasons, but two of them are the most important. From 1975, I found Rajiv to be ever clean when it came to moral behavior - wine, women, and wealth.

Whenever I have got any electronic gadget for him, he had always insisted to pay me the price. It was simply out of his character to even tolerate personal bribes, let alone demanding them. Secondly, when the matter was getting fiercely debated in the Parliament, Rajiv had categorically stated that he and the Swedish Prime Minister had together agreed to ensure that there were no commissions paid. Had he any knowledge of the payoffs, he could have coolly announced that, “In such international deals for the sale of weapons, there always could be involved paying commissions, and we will investigate the matter and if anyone is found guilty, we will give severe punishment to everyone involved.” He instead insisted that there were no commissions paid. Why would he do it if he was personally guilty?

Rajiv Gandhi: Politically Misfit Prime Minister

Certain actions and decisions by Rajiv proved the worst in the long run for the nation, especially his inept handling of orthodox religious issues, such as the Shahbano case or the Babri Masjid issue. On a hinder sight, probably a more rational and uncompromising stand could have served the nation better.

His ill-advised decision of sending IPKF to Sri Lanka is perhaps one of the worst decisions by any Prime Minister of India. Primarily, he was too naive and straight-forward person to understand the tricks of real politics; international diplomacy even less. Unfortunately, ill-advised IPKF finally cost him his life. Luckily, Sri Lankan-Tamil issue has been largely resolved, even though it haunted both the countries long after his assassination on May 21, 1991.

Rajiv always acted in good faith, and was positive and upbeat about India. He was convinced about modern technology as a vehicle for India's progress. He surely ushered India into a new world of computers and communications and gave a push to the growth of the electronic industry. During his leadership, the Indian electronics industry showed remarkable growth; production grew eight folds in six years of his being in politics. He prepared the nation for modernization through Information Technology just when that word itself was coined. That initiative has made it easy for us to smoothly move into the current Digital World of the Internet, smartphones, and smarter citizens. Young Indians, literate or illiterate, have taken to high technology with ease while the elderly, who refused to learn and change, are slowly getting pushed out. Rajiv Gandhi will always get the credit for laying its foundation. As his technology advisor ever since he entered politics in 1981, until he died in 1991, I have actively participated in that process.

However, one can't forget some of his serious retrograde decisions, albeit they were basically from his political advisors. I feel he became unsure of his grip over politics and he, therefore, changed his political advisors from time to time. Lack of experience in dealing with manipulative politics in Delhi obliged him to depend on advisors, and lack of diplomacy made him change them. A list of his political colleagues who moved away from him or who were swept away by him is long and it shows his unsure mind.

I often wish that he should have kept away from politics since it indeed was not his cup of tea. The poor fellow got dragged into the Bofor corruption scandal despite being morally and emotionally as clean as one can be. Sonia Gandhi was right when she fought tooth and nail to dissuade him from becoming the Prime Minister on the 30th of October 1989.

- P. S. Deodhar

psdeodhar@aplab.com

(The author - an entrepreneur and former Chairman of Electronics Commission, Government of India, was Advisor (Electronics) to Rajiv Gandhi.)

The Marathi translation of this article will be published next week on Kartavya Sadhana.

Tags: rajiv rajiv gandhi p s deodhar prime minister politics congress emergency bofors birth anniversary political indira gandhi sonia gandhi Load More Tags

Add Comment