(As the world gears up to celebrate International Day of Disabled Persons on December 3rd, Kartavya will be publishing a five-part series that focuses on the lives of disabled people in Pune, concerning several aspects of their lives, laced with their own experiences - pre and post the ongoing pandemic.

Pune, being the education hub of India, attracts students from all over the country, many of whom are persons with disabilities. The first part of this series thoroughly explores their experiences and approaches about the education system and its modus operandi from the perspective of a person with disabilities. Comments from people associated with organizations working for the disabled further authenticate the grassroot scenario of the disabled people’s lives in Pune.)

Fool’s gold glitters, doesn’t sell

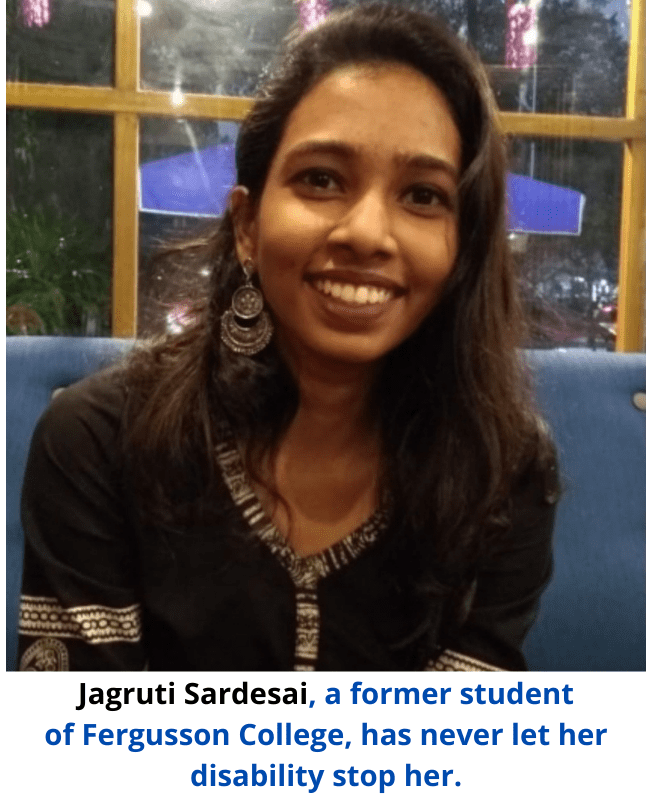

Jagruti, who has a neurological disorder called muscular dystrophy that has paralyzed both her lower limbs, completed her graduation just last year. She is one of the very few disabled who do not use their reservation quota to get admissions.

“It sounds good when you hear 4% quota reserved for the disabled. It seems like the government really has its concerns for the disabled in place. There are even job reservations. But have you ever thought that there are 21 types of disabilities of starkly different nature from each other and all of them fall under ‘disabilities’ without being categorized? When a paraplegic who can see, hear and talk just fine, competes with other students who can’t do all that, how fair is the competition? I don’t intend to take advantage of my disability when I am completely capable of going on about my life without such provisions with major loopholes,” said this vibrant young lady.

“It sounds good when you hear 4% quota reserved for the disabled. It seems like the government really has its concerns for the disabled in place. There are even job reservations. But have you ever thought that there are 21 types of disabilities of starkly different nature from each other and all of them fall under ‘disabilities’ without being categorized? When a paraplegic who can see, hear and talk just fine, competes with other students who can’t do all that, how fair is the competition? I don’t intend to take advantage of my disability when I am completely capable of going on about my life without such provisions with major loopholes,” said this vibrant young lady.

The problem that she pointed out is the most basic and a big loophole in the disability provisions system. All the 21 disabilities listed in the RPWD Act of 2016 need to be categorized on priority before renewing or introducing newer provisions. It is simple logic that a person with a mild disability like low vision cannot be a fair competition to a person who has hearing or sight impairment. The repercussions of such unthoughtful provisions are reflected upon the literacy statistics of the disabled every year.

Only 2.2% of the total population of India (2.68 crores) falls under the disability category, according to the 2011 census. Only 14.6% of that population (39.12 lakhs) is literate. If the statistics are further narrowed down, only 1.25% of the disabled (3.2 lakhs) pursue higher education. It means only 3.2 lakhs of the 2.68 crore disabled people are well educated in our country. This scenario is unarguably a bad one, and it has many reasons that most of the abled people conveniently slide under the carpet of disability quota.

One of them is accessibility issues while pursuing education. If one is to admit their child with a disability to a normal school or university, the first thing they will take into consideration is whether the campus is access friendly for the disabled. This consideration is highly likely to lead to disappointment.

Rarely are there schools and colleges that necessarily have ramps, disabled-friendly washrooms, elevators, and lifts with sound technology and braille installed in them, even when an access-friendly architecture in government institutes is a compulsory provision, as mentioned in the National Policy for Persons with Disabilities Act of 2006.

Considering the entire COVID-19 scenario with newer education practices, the authorities haven’t taken note of the accessibility issues that a blind or deaf student may face. The online meeting apps like Zoom or Google Meet are not disabled friendly and become extremely difficult to operate for the disabled.

Mahima, a blind student from Fergusson College, admits that one benefit of attending actual physical classes was that the teachers and students looked out for her and made sure that she understood everything. Online classes don’t grant her that advantage. Online exams that were conducted by almost all institutes in Pune recently were also problematic for the hearing, speech, and sight-impaired students. “Having a writer appointed from the college/university, and finding one here in my hometown is not the same thing. It’s extremely difficult here,” shares Yogesh – another blind student.

With old teaching practices lacking absolute inclusivity for the disabled, to have it in the newer, developing teaching techniques is certainly a high expectation. If this line of thought is given further depth, it will come to light that the rich and privileged class of disabled people will move forward conveniently, while the ones who can’t afford to go beyond the government facilities will stop pursuing education after the primary or secondary level is completed. Owing to the pandemic, it is quite possible that many disabled students, especially the ones who can’t afford mobile phones or laptops, will either take a break or quit their education only because of the unavailability or inefficiency of the medium.

The roads never taken lead to places never seen

Despite a reservation for the disabled in all government and government affiliated institutes as mentioned in the RPWD Act 2016, the quota gets rarely completely filled. Very few parents prefer sending their children with disabilities to a school with abled students and teachers.

Diksha, a paraplegic young woman, has a neurological condition that paralyzed her lower limbs at birth. Her parents were rare to decide on sending their daughter to a normal school. “Initially, I didn’t face a lot of problems. My class used to be on the ground floor and the teachers were supportive. Even the school hours were not too long initially. But later as I grew up, they had to shift our class to the ground floor because of me. I needed assistance every time I needed to use the washroom. It gradually became embarrassing. There weren’t toilets for the disabled. And the teachers that I got later weren’t really friendly,” Diksha recalled. What Diksha faced as a child are the primary reasons parents don’t want to send their physically challenged children to normal schools.

Another provision in the RPWD Act says that there should be enough ‘Teachers Training Institutes’ where the teachers will be trained about how to deal with students with different kinds of disabilities. This is one of the most vital provisions to promote quality education for the disabled but unfortunately, it only remains on paper. Rarely are there schools and colleges in Pune with teachers trained with Braille, Sign language, and other basic teaching tactics for the disabled.

“Why don’t they just make it a criterion to be a teacher? They should simply make it compulsory for a person to know at least braille and sign language to qualify as a teacher,” suggested Yogesh.

Dr. Mathew Martin, a senior researcher in auditory-verbal therapy, is currently working on a project that studies the cognitive abilities of hearing-impaired children. He says they have brilliant abilities to sense things. Their smelling and visual senses work much more vigilantly than a normal human being. While talking to him, an excellent suggestion came across –“Why is it that we focus on educating the disabled to adapt to how abled students learn? Wouldn’t it be easier if the abled students are taught to deal with the disabled learning techniques instead?”

What Yogesh and Dr. Martin said shows a totally different, alternate possibility to look at disability-related issues. The way we perceive solutions might not necessarily be in the right direction. It seems going the other way round, in this case, is a brilliant idea – do not ask the disabled to adapt with the abled, do the opposite. Take that road never taken instead, and things will suddenly become easier. But this way or that, execution is what seems to be the perpetual problem that awaits.

The kings are actually just some (bad) servants

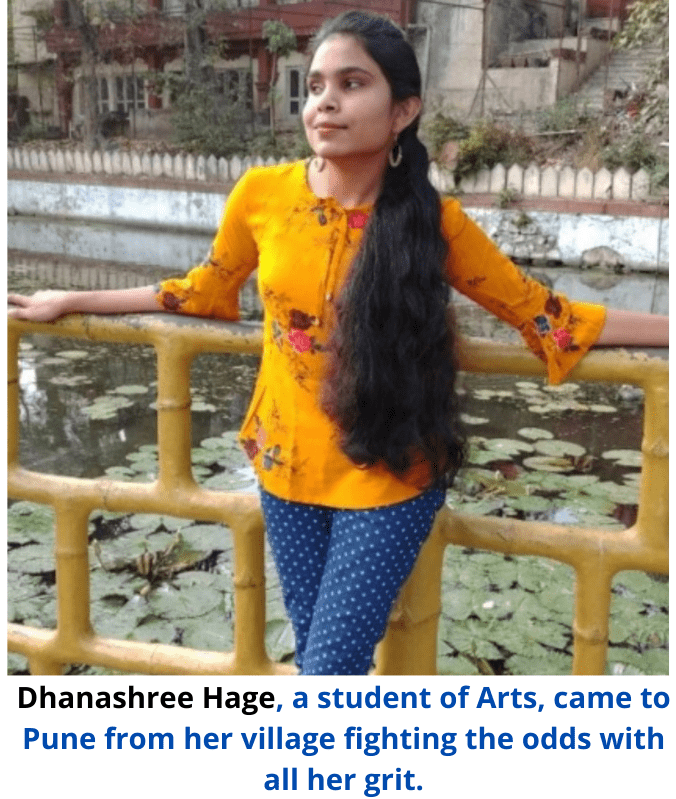

Dhanashree, who suffers from blindness and muscular dystrophy in her upper limbs, was waiting for one of the volunteers who work for a student based NGO for the blind, called the Saathi Enabling Centre in Fergusson College. It was her exam 4 days later, and she needed to get her study material audio recorded. To her discontent, the volunteer called and told her he couldn’t come because he had his own study to finish. Dhanashree went home, worried that this time she might not be able to score well. The volunteer, however, turned up the next day after his exam and recorded a few chapters for her to refer to. She was relieved, but she knew her luck will some or the other time, cause her dismay. As much as she was striving to become a blind yet independent woman, she knew the journey involved a lot of dependencies.

Dhanashree, who suffers from blindness and muscular dystrophy in her upper limbs, was waiting for one of the volunteers who work for a student based NGO for the blind, called the Saathi Enabling Centre in Fergusson College. It was her exam 4 days later, and she needed to get her study material audio recorded. To her discontent, the volunteer called and told her he couldn’t come because he had his own study to finish. Dhanashree went home, worried that this time she might not be able to score well. The volunteer, however, turned up the next day after his exam and recorded a few chapters for her to refer to. She was relieved, but she knew her luck will some or the other time, cause her dismay. As much as she was striving to become a blind yet independent woman, she knew the journey involved a lot of dependencies.

“Considering the disability statistics, it is a simple calculation that at least 2 students getting admission from disability quota every year will be blind. Then why don’t they provide audio-books and braille study material?” asked Dhanashree furiously.

A conversation about this with an NGO coordinator named Vishal revealed that the NGO is itself helpless with the whole scenario. “The syllabus changes quite frequently. Which means the audios of the books that we record gradually expire. Besides, teachers recommend different reference books, most of which are impossible to completely read for even sighted students. There’s no definite study material. We try our best to record books for every student, but the volunteers don’t always get enough time to record everything,” he clarified.

Dhanashree’s question made me estimate the amount of investment institutes like Pune University or Fergusson College would require to appoint writers and to make audiobooks and braille books available for the blind students - it is almost negligible for Pune’s topmost institutions like these. What comes in the way is sheer ignorance, or maybe, the lack of awareness of the urgency of the situation. The students do just fine without braille or audiobooks. But the possibility of them doing even better is never explored.

When asked about any official requests sent by the students to college authorities, it seemed that most of them are content with the reservation quota that they have been given. “We feel indebted to Saathi and Fergusson College for giving us a comfortable environment,” said one of the blind students.

Their gratitude was legitimate, but it wasn’t necessary. These students are compromising their rights without even realizing it. Their dependency is making them feel obliged to be grateful towards society, which is another subtle problem of the society mindset, especially in the case of education. They must realize that they deserve to be properly educated as much as any ordinary student. Their needs, their requirements to be able to pursue their education properly, are not their responsibility once they are a student of a particular institute. But if the institute itself fails to make them realize that, whose fault is it really?

While the 2011 census primarily estimates the total percentage of disabled people to be 2.2 in the country, an external research paper titled ‘India’s Disability Estimates: Limitations and way forward’ (Dandona R, 2019) concludes that ‘the estimates from the census and surveys seem much lower than would be expected at the current population level of India’.

This research, done by Ph.D. fellows from the Public Health Foundation of India, puts light on a big loophole that persists in our statistical beliefs about disability estimates. The statistics we believe to be true, might not necessarily be true. To change the situation of the PWDs in India, we’ll have to start by questioning the official on-record statistics about them. This is how deep in water we are.

Despite several obstacles, there have been terrific examples of disabled people doing extra-ordinary things if given the right opportunities. It is high time that we realize the need to imprint a progressive approach in not just the minds of the abled but also in that of the disabled people. What they need to realize more necessarily is that a person’s disability should not make him feel indebted to his society for providing him with his needs. It is as much his right to receive proper education as it is of any other human being. We have a long way for this thought to get normalized. Acknowledging it is the first step; ahead awaits a way that needs to be walked on slowly and steadily until disability and capability become completely unrelated terms.

- Aishwarya Dakhore

aishwaryadakhore@gmail.com

(This article was written and improvised by the author as a part of an in-depth report submitted to the Department of Communication and Journalism, Savitribai Phule Pune University. The author holds an interest in writing about issues related to human rights, gender issues, and politics.)

Other articles in this five-part series:

Part 2: Disability Stigma: The Real Kingpin

Part 3: Inaccessible Pune of ‘Accessible India’

Tags: civic human rights disability people with disabilities disabilities education system series aishwarya dakhore Load More Tags

Add Comment