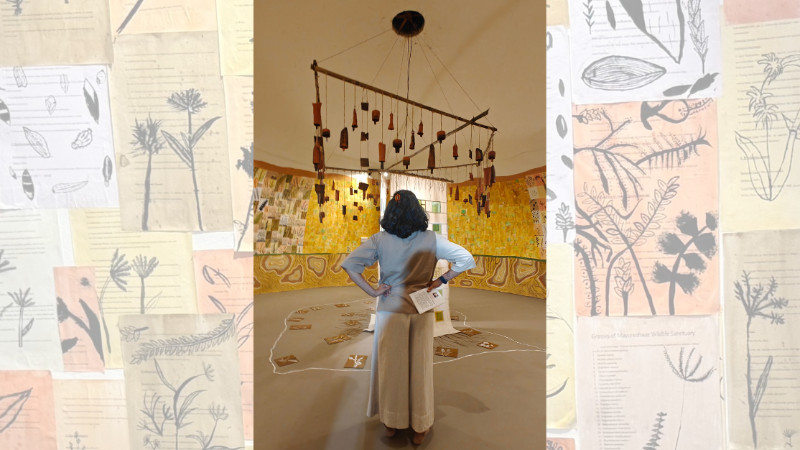

The third edition of Growing Museum, conceptualised and curated by me, marks a significant turning point in the project’s journey. Held at Deulgaongada — a small village shimmering with fields of grass — this edition was the first to emerge as an artist collective. While the earlier editions at Gunehad in Himachal Pradesh and Sonale in Wada taluka were conceived and executed solely designed and conducted by me, this one grew through shared authorship. Six visual artists from different fields joined hands with me. Alongside them, children, teachers, and community members became co-creators, shaping both the form and spirit of the installations.

Growing Museum is an evolving body of work that has grown from two decades of working with children across India. Each edition unfolds within a unique landscape — mountains, farmlands, or grasslands — and reveals how local ecology and culture shape children’s imagination. Through the intertwining of art, anthropology, and pedagogy, it explores how children’s creativity reflects their environment and sense of belonging.

What emerges is not just an exhibition, but an ecosystem of collective imagination — a living museum that grows through participation, community, and shared acts of creation.

My Journey: From Sculpture to Ethnography

My path to Growing Museum began long before its first edition took shape. I did my graduation in Sculpture and my post-graduation in Archaeology — disciplines that taught me to see both material and memory as layered entities. Sculpture trained me to think through form and space; archaeology taught me to read traces, silences, and continuities.

My path to Growing Museum began long before its first edition took shape. I did my graduation in Sculpture and my post-graduation in Archaeology — disciplines that taught me to see both material and memory as layered entities. Sculpture trained me to think through form and space; archaeology taught me to read traces, silences, and continuities.

When I began designing workshops for schools, I instinctively started combining art and archaeology. Children created clay relics, imagined ancient settlements, and drew their own rock art. These sessions revealed something profound — that children perceive their sense of identity through the stories they inherit and the art they make.

This discovery eventually led to my Ph. D. research: How children perceive their sense of identity through history and art education, and how visual art serves as a window into their psyche.

The Growing Museum is a direct extension of that research. I designed its conceptual framework in 2015, and the first physical edition came alive in 2020. My future plan is to transform it into a sustainable model — one that allows children to continue building their own small museums within communities, celebrating their cultural and ecological worlds through creative expression.

Rooted in Children

For more than twenty years, my artistic and anthropological journey has been intertwined with children — their laughter, curiosity, and unfiltered ways of seeing. I have worked with them in classrooms, museum spaces, and open fields across India.

Each time, I have witnessed a quiet kind of brilliance: the ability to turn the ordinary into something luminous — a stone into a story, a leaf into a map, a line into memory.

My approach to teaching always carries an ethnographic sensibility. I design workshops that encourage children to reinterpret rock art, ancient symbols, or local patterns through drawing and collage. Their art becomes data — a form of visual ethnography that reveals how they experience time, nature, and belonging.

A mountain child draws with vertical strokes of wind; a coastal child with ripples and tides; a forest child with networks of roots and veins. Each drawing is not just an artwork — it is an ethnographic document of place, psyche, and imagination.

A Field of Grasses, a Seed of Thought

A Field of Grasses, a Seed of Thought

The idea for the Deulgaongada edition germinated in the fields themselves. The grasses here swayed like sea waves — resilient, rhythmic, endlessly adaptable. They became metaphors for survival and continuity.

I wanted the children of Deulgaongada to see their landscape as a living presence — not just background, but collaborator. We began a series of workshops called Grasses of Deulgaongada, with thirty-two children from the local school.

We walked through the fields, observed how the grasses changed colour through the day, and watched how their roots intertwined beneath the soil. The children drew, collected, pressed, and imagined. Some found faces in seed heads; others drew homes for birds. Their sketches were wild, unpolished, and alive.

It was then I realised that their drawings were not the outcome of a workshop — they were the beginning of a conversation.

When Children’s Work Becomes My Medium

That realisation transformed my practice. Instead of displaying children’s works as separate “outputs,” I began to treat them as material — integrating their gestures, drawings, and textures into my own installations.

The dome became the experimental site. We collaged their drawings on research papers, layered them over maps and text, and allowed them to bleed into my compositions. The children drew on discarded research notes and field maps, turning data into imagery. We made herbariums, grass-shaded fabrics, jigsaw puzzles, and bells imprinted with grass impressions.

For the first time, I was not simply teaching children to make art — I was learning from their process. Their uninhibited approach to form and rhythm reconfigured my own methods. I began to let their spontaneity guide the structure of the space.

This was not just pedagogical inclusion — it was artistic collaboration.

Children as Co-Creators

Inside the dome, the installations grew organically — like branches from a common root. Every wall, texture, and suspended element carried traces of children’s imagination. A scribble became a mural of wind; a cluster of brushstrokes turned into roots; a pressed grass became light.

The moment that stays with me most is when a child recognized her drawing integrated into a glowing wall and whispered, “That’s mine.”

That whisper contained everything the Growing Museum stands for — belonging, recognition, and the transformation of the child’s gaze into authorship. The museum was no longer something distant or formal. It was theirs.

By allowing multiple mediums to converse — drawings, textures, textiles, sound, and light — we turned the dome into a breathing organism. Each element resonated with the community’s rhythms, capturing the intertwined lives of children, land, and memory.

Building the Museum Together

The dome structure itself became a metaphor for growth — circular, transparent, and open to the sky. In a small village like Deulgaongada, technical support is scarce. Yet, electricians, teachers, and villagers joined hands with us. We improvised materials, adapted designs, and learned from one another.

Initially, I believed my team comprised six artists and thirty-two children. But soon I realised it also included everyone who participated invisibly — the teacher who arranged the space, the villager who brought us tea, the electrician who patiently adjusted the lights.

Together, we didn’t just build a museum — we built a collective spirit.

The Two-Way Advantage

When children’s art becomes my medium, the process gains a two-way depth.

For the children, it instills ownership and confidence. They see their imagination occupying real space — not confined to paper, but forming part of an installation. They learn that their ideas matter.

For me, it’s a return to innocence. Their freedom from rules and fear of failure reminds me of creation’s purest form. Their gestures invite me to unlearn — to replace precision with play, analysis with wonder.

This reciprocity — where teaching becomes learning and learning becomes creation — lies at the heart of the Growing Museum.

हेही पाहा - ‘गोवन डिलाईटस्’ या पुस्तकाचे लेखक चित्रकार तुषार शेट्टी यांची विनोद शिरसाठ यांनी घेतलेली मुलाखत

Extending the Museum Beyond Walls

Parallel to the installation, we created three books under the same project — Grasses of Deulgaongada — launched by Madhuri Purandare and Sandhya Taksale.

Each book extends the museum into new forms:

गवत बिवत घरटं बिरटं — a picture book written by Archana Bhat and illustrated by Sawani Puranik

An information book by Sonali Navangul, illustrated by Sawani Puranik

Before It Fades — a colouring book by Prajkta P

Together, they translate the dome’s spirit into narratives and illustrations that travel beyond the site — into homes, libraries, and classrooms.

The books invite readers to notice the invisible — the grasses underfoot, the textures of silence, the overlooked beauty of everyday life.

Visual Anthropology and Ethnography

Visual Anthropology and Ethnography

As a visual anthropologist, I view images as both evidence and emotion — as ways of knowing the world beyond words. Visual anthropology studies how humans express, remember, and interpret their surroundings through imagery, objects, and forms.

Ethnography, meanwhile, is about presence — entering a community, observing, and understanding from within. It values participation and empathy over distance and detachment.

When art and ethnography intersect, making becomes a method of knowing. Each artwork becomes a field note; each installation, an archive of lived experience.

In Growing Museum, children are not merely subjects of observation — they are co-ethnographers. Their art becomes data, expression, and reflection all at once. The museum thus operates as a visual ethnography — a living record of how imagination, ecology, and community entwine.

In the End, Everything Grows

As the evening light fades over Deulgaongada, the dome glows like a seed under the sky. The air hums softly; shadows ripple over collaged walls. Somewhere, a child’s laughter echoes through the grasses.

In that moment, the boundary between art and life dissolves. The museum is not an exhibit — it is a living being, breathing through shared imagination.

When I step back and look at it all — the children’s gestures, the community’s effort, the grasses that inspired it — I realise that Growing Museum is not about what we built, but how we grew together.

It is a practice of slowing down, listening deeply, and allowing growth — in art, in relationships, and within ourselves.

In the end, it is not just a museum that grows.

It is us.

- Dr. Anagha Kusum

anaghakusum@gmail.com

(Dr. Anagha Kusum is a Visual Artist and Visual Anthropologist based in Pune. She has spent two decades designing and conducting art-based workshops for schools, integrating art and archaeology. Her PhD explores how children perceive their sense of identity through history and art education. and how visual art becomes a lens into their psyche.)

Tags: Anagha kusum visual arts visual anthropology growing museum art museum deulgaon gada gunehad sonale children Load More Tags

Add Comment